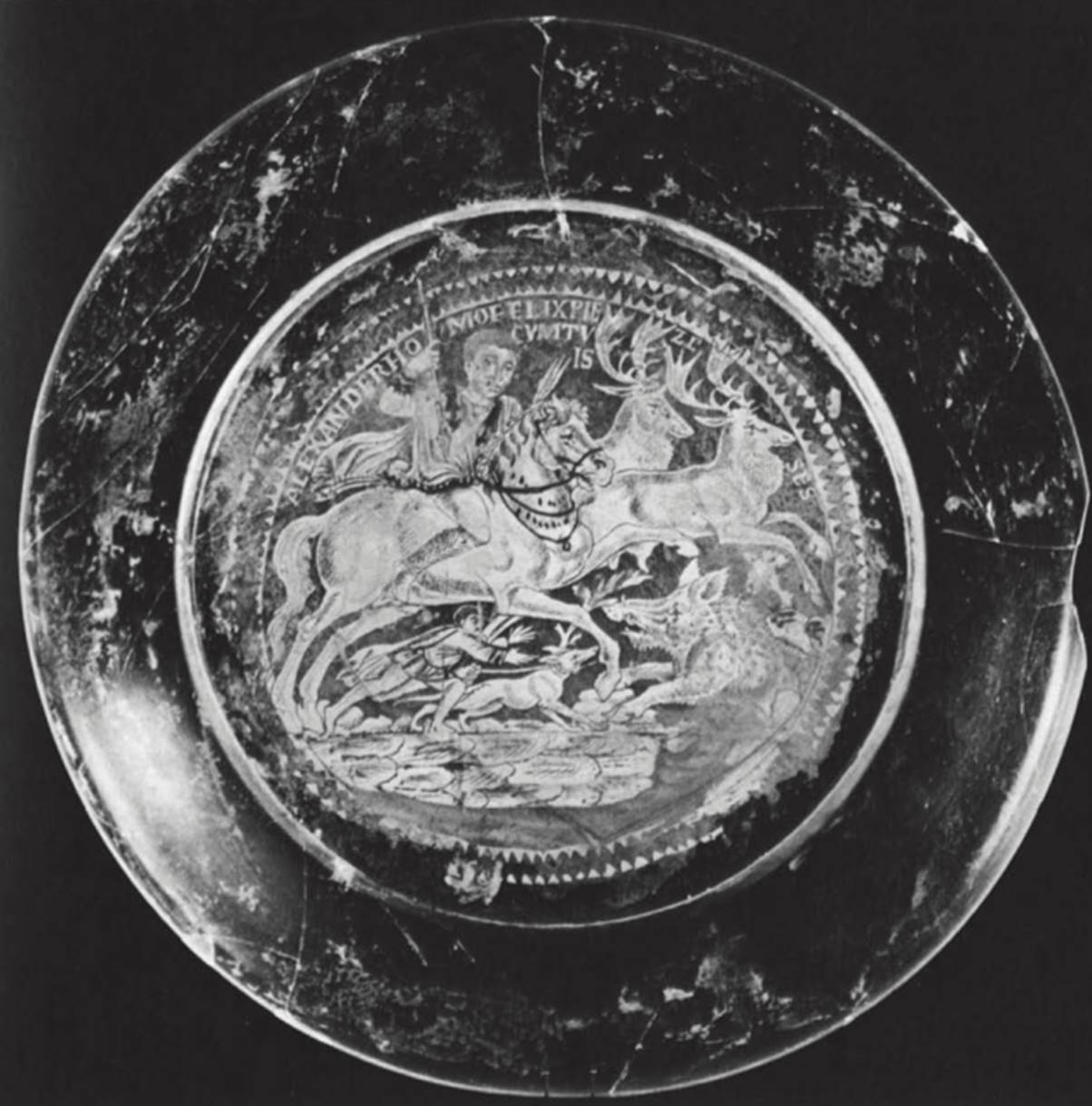

Alexander plate with hunting scene. Italy, mid-3rd century Gold glass

The Alexander plate belongs to a precious class of shallow glass dishes, enriched at the base by a gold-glass disc, fused to the body of the dish and decorated chromatically by a figured design meant to be seen from above. The finest of these gold glasses are dated in the third through the fourth century, and, although they have often come from Italian catacombs, there is no evidence that, as a class, they were originally destined for sepulchral use. Their high quality and chromatic richness demonstrate the preference for splendid luxury in the minor arts that so fully characterized Late Antique art (cf. Prudent. C. Symm. 2. 489).

Typically, this plate was executed in two parts, the large upper section in green blown glass, and the concave lower disc of greenish glass which contained the gilded and painted decoration. Gold leaf was applied directly to the glass for much of the scene with additional details painted over in red and white; the white rocks at the bottom were painted on a reddish brown base, and a green pigment was painted on the glass around them. Fine lines, masterfully drawn by a sharp point through the gold leaf, expose the greenish glass below, seen as black against the gold. A reciprocating border motif frames the disc, a device used in another glass medallion in the Vatican Museum (Cooney, 1969, fig. 4) and possibly the mark of an atelier. At some time the entire surface of the glass was deliberately abraded to remove iridescence caused by decay, which might have obscured the design.

The scene depicts a richly dressed horseman accompanied by his hunting dog and a groom; his throwing spear is raised high in the right hand with spares held in the left, as he pursues two elk and a boar who turns at bay. These animals were favored prey of the aristocratic hunters of the late empire, who tested their skill and proved their virtus in the hunt. Similar themes enriched many public and private works of art from con- torniates and sarcophagi to the Hadrianic tondi on the Arch of Constantine (no. 58).

The hunt was considered to be symbolic of transcendent victory. The inscription, Alexander homo felix pie zeses cvm tvis (“Alexander, fortunate man, may you live [long] with your family and friends in affection"), reinforces the idea of the hunter as a victor, and most scholars have recognized here another evocation of Alexander the Great. This Alexander, however, has been given contemporary clothing and a physiognomy characteristic not of the Hellenistic period but of Roman portraiture in the third century. Cooney (1969) and Engemann ([1], 1973) believe that the portrait style can be dated to about 275, if not later, but Greifenhagen (1971), judging both by appearances and by the name, thought that the Roman emperor Alexander Severus (222-235) was represented.

As Engemann ([1], 1973) observed, it is inconceivable that an emperor could be called simply homo, "man," and not by one of his regal titles; therefore, that identification is unlikely. Yet, the simple, pyramidal shape of the head, the close-cropped hair, large eyes, and sensitive mouth, when considered together with the subtle modeling effected by hatched lines, are stylistic features of Roman portraiture from about 230-255 and especially of the time of Gordian III. Thus, the plate may be dated to within this period. It is a luxurious object created in the imperial manner but for a private, aristocratic patron.

Disc intact about 1900, broken 1968, restored 1969. Bibliography: Cooney, 1969, pp. 253-261, cover ill.; Greifenhagen, 1971; Engemann (1), 1973.

Date added: 2025-07-10; views: 47;