Food allergies. IgE-Mediated Food Allergies

True food allergies can occur through two different immunological mechanisms, the humoral or antibody-mediated mechanism and the cellular mechanism. The most common type of food allergies involves mediation by immunoglobulin E or IgE.

A. IgE-Mediated Food Allergies. IgE-mediated food allergies are sometimes called immediate hypersensitivity reactions because of the short onset time (minutes to a few hours) between the ingestion of the offending food and the onset of allergic symptoms. In IgE-mediated food allergies, the body produces allergen-specific IgE in response to exposure to a food allergen, usually a protein. The IgE antibodies are highly specific; the formation of IgE specific to one food will not confer allergy to another food unless the two foods are closely related and cross-reactive.

Some food proteins are more likely to elicit IgE antibody formation than others. Although exposure to the food is critical to the development of allergen-specific IgE, exposure will not invariably result in the development of IgE antibodies even among susceptible people. Many factors are likely to influence the formation of allergen-specific IgE antibodies, including the susceptibility of the individual, the immunogenic nature of the food and its proteins, the age of exposure, and the dose, duration, and frequency of exposure.

The allergen-specific IgE is produced by plasma cells and attaches itself to the outer membrane surfaces of specialized cells called mast cells and basophils. Mast cells are present in many different tissues and basophils are found in the blood. In this process, known as sensitization, the mast cells and basophils become sensitized and ready to respond to subsequent exposure to that particular food allergen. However, sensitization is symptomless, and no adverse reactions will occur without subsequent exposure. Sensitization to a particular allergen distinguishes allergic individuals from nonallergic individuals.

Once the mast cells and basophils are sensitized, subsequent exposure to the allergen results in the release of a host of mediators of allergic disease that are either stored or formed by the mast cells and basophils. The allergen cross-links two IgE molecules on the surface of the mast cells and basophils, which elicits the mediator release. Mast cells and basophils contain large numbers of granules that store certain mediators that are released during this process. Several dozen different mediators have been identified. Histamine is one of the primary mediators of IgE- mediated allergies and is responsible for many of the early symptoms associated with allergies. Many of the other mediators, such as the prostaglandins and leukotrienes, are involved in the development of inflammation.

The interaction of a small amount of allergen with the allergen-specific IgE antibodies results in the release of comparatively large quantities of mediators into the bloodstream and tissues. Thus, exposure to trace amounts of allergens can elicit symptoms. This mechanism of IgE-mediated reactions is involved in many different types of allergies to foods, pollens, mold spores, animal danders, bee venom, and pharmaceuticals. Only the source of the allergen is different.

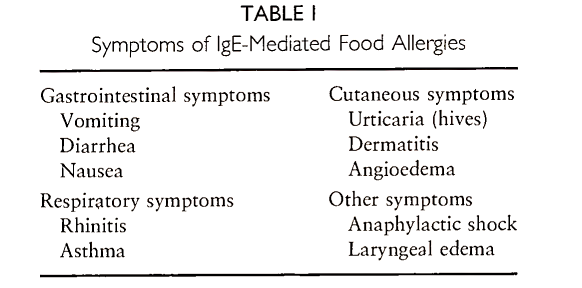

A variety of symptoms can be associated with IgE- mediated food allergies (Table I). The nature of the symptoms will depend on the tissues affected by the various mediators. Fortunately, allergic individuals typically suffer from only a few of the many symptoms. With food allergies, symptoms associated with the gastrointestinal tract are quite common since this is the organ of insult after ingestion of food. Skin symptoms are also fairly common. Respiratory symptoms are less frequently involved with food allergies than with various inhaled allergens such as pollens and animal danders. However, asthma is a very serious, though uncommon, manifestation of food allergies.

Most of the symptoms of IgE-mediated food allergies are not particularly definitive. The gastrointestinal manifestations of food allergies can also be associated with many other causes. Though there are millions of asthmatics, relatively few are allergic to foods.

Anaphylactic shock is by far the most serious manifestation of food allergies. Thankfully, very few individuals with food allergies experience anaphylactic shock after ingestion of the offending food. It involves multiple organs and is often accompanied by gastrointestinal, cutaneous, and respiratory symptoms in combination with a dramatic fall in blood pressure and cardiovascular complications. Death can ensue within minutes of the onset of anaphylactic shock.

The severity of an allergic reaction will be dependent to some extent on the amount of the offending food that is ingested. If an exquisitely sensitive individual inadvertently eats a large amount of the offending food, their reaction will be more serious than if the exposure was to a trace amount. Yet, trace quantities can elicit noticeable reactions owing to the large release of mediators.

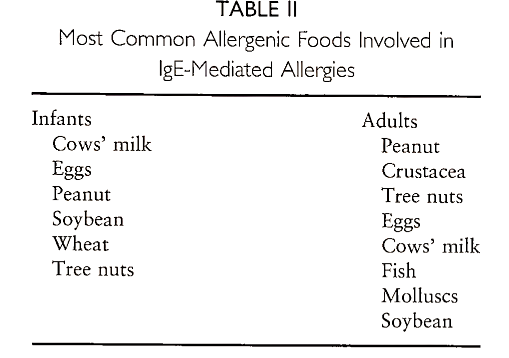

The most common allergenic foods in the United States are listed in Table II. To some extent, the most common allergenic foods vary from one culture to another. Peanut allergy is more common in the United States than in most other countries, probably because peanuts are eaten more often in the United States and peanut butter is introduced at an early age. In Japan, soybean allergy is very common, probably because the Japanese eat large quantities of soybeans. Any food that contains protein has the potential to elicit an allergic reaction in someone. The most common allergenic foods tend to be foods with high protein content that are frequently consumed. The exceptions are beef, pork, chicken, and turkey, which are uncommon allergenic foods despite their frequent consumption and high protein content.

The prevalence of IgE-mediated food allergies is not precisely known. Infants have the highest prevalence of such allergies, estimated at 4-8%. Cows’ milk is the most common allergenic food in infancy, followed by eggs and peanuts. The prevalence of IgE- mediated food allergies in older children and adults is even less certain. However, the prevalence in adults is thought to drop below 1% of the population. Thus, many infants and young children outgrow their IgE- mediated food allergies. The reasons for the development of tolerance to previously allergenic foods are not understood, but may involve the development of blocking antibodies of other types, especially IgG and IgA. Allergies to some foods, such as cows’ milk and eggs, are more frequently outgrown than allergies to other foods, such as peanuts. Thus, peanut allergy is the most common food allergy among adults, at least in the United States.

The diagnosis of food allergies is typically a stepwise practice. A good medical diagnosis is important because parental diagnosis and self-diagnosis are often wrong, identifying incorrect foods and identifying too many foods. Most individuals with IgE-mediated food allergies are allergic to one or two foods, rarely to more than three foods. Occasionally, allergies can exist to a group of closely related foods, for example, the Crustacea (shrimp, crab, lobster, and crayfish). Thus, the goal of medical diagnosis is to establish a cause-and-effect relationship between one or a few foods and the onset of allergic symptoms. Once that has been determined, the involvement of IgE must be ascertained.

Most physicians begin the diagnosis by compiling a careful history of the patient’s adverse reactions. Critical information would include the identity of the foods eaten immediately before the onset of symptoms, the amount of various foods consumed, the type, severity, and consistency of symptoms, and the time intervals between eating and the onset of symptoms. In complicated situations, histories are often needed from several episodes to reach a probable diagnosis. Challenge tests with the suspected food(s) are often necessary to establish with certainty the role of a specific food in the reaction.

The double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenge (DBPCFC) is considered the most reliable procedure. In the DBPCFC, neither the patient nor the medical personnel know when the food (in capsules or disguised in another food or beverage) is going to be administered and when the placebo is to be administered. Thus, the DBPCFC is free of bias. Single-blind and open challenge tests also have value in some situations. Sometimes, history alone is sufficient to make the diagnosis if the cause-and-effect relationship is particularly compelling. Challenge tests are seldom used on individuals who experience life-threatening allergic reactions.

The diagnosis of an IgE-mediated mechanism can be made with either the skin prick test (SPT) or the radioallergosorbent test (RAST). The simplest procedure is the SPT, in which a small amount of a food extract is applied to the patient’s skin and the site is pricked with a needle to allow entry of the allergen.

A wheal-and-flare response (basically a hive) at the skin prick site demonstrates that IgE affixed to skin mast cells has reacted with some protein in the food extract. Histamine usually serves as the positive control. An alternative procedure is the RAST, which uses a small sample of the patient’s blood serum. In the RAST, the binding of serum IgE to food protein bound to some solid matrix is assessed using radiolabeled or enzyme-linked antihuman IgE. The RAST is considerably more expensive than the SPT and is equally reliable, sensitive, and specific. The RAST is preferred for patients with extreme sensitivities. It should be emphasized that a positive SPT or RAST in the absence of a history of allergic reactions to that particular food is probably meaningless. The SPT and RAST are the most frequently used and reliable tests to assess the role of IgE in an adverse reaction.

The primary means of treatment for IgE-mediated food allergies is the specific avoidance diet, for example, if allergic to peanuts, don’t eat peanuts. With IgE- mediated food allergies, the degree of tolerance for the offending food is often very low, so the construction of a safe and effective avoidance diet can be quite difficult. The contamination of one food with another from the use of shared processing equipment and preparation equipment (utensils, cooking surfaces, pots and pans, etc.) can be sufficient to elicit an allergic reaction. Also, patients must have considerable knowledge of food composition and recognize the sources of ingredients. For example, casein, whey, and lactose are ingredients derived from cows’ milk and would be hazardous for individuals with cows’ milk allergy.

The ingredient must contain the protein component, which some foods (e.g., peanut oil and soybean oil) do not unless they have been contaminated during use. The careful scrutiny of food labels is critical to avoidance of allergic reactions. But undeclared uses of food can occur, especially through restaurant meals. As a result, many inadvertent exposures occur among allergic consumers who are attempting to avoid their offending food(s).

Cross-reactions are another perplexing issue for food-allergic consumers. Cross-reactions do not always occur between closely related foods, for example, many individuals are allergic to peanuts and most of these are allergic only to peanuts. A few of these individuals are cross-reactive with one or more other legumes, usually soybeans. Cross-reactions frequently occur among the Crustacea but less commonly among the finfish. Cows’ milk and goats’ milk invariably cross-react, as do the eggs of various avian species. Cross-reactions can also occur between foods and other environmental allergens. The most common examples are the cross-reactions between some fresh fruits and vegetables and certain pollen allergies in some individuals and the cross-reaction between natural rubber latex and bananas, kiwis, and chestnuts. The basis for cross-reactions is frequently not known.

Attempts to prevent the development of food allergies in susceptible infants are often futile. Infants born to parents with histories of allergic disease are much more likely than other infants to develop food allergies. The avoidance of commonly allergenic foods such as cows’ milk, eggs, and peanuts primarily through breast feeding appears to delay but not prevent the development of food allergies.

A few specialized hypoallergenic foods are available in the marketplace. These foods are intended for infants who have developed allergies to infant formula made with cows’ milk. The most effective hypoallergenic infant formulae are based on extensively hydrolyzed casein. Although casein is a common milk allergen, the hydrolysis of its peptide bonds renders it safe for most cows’ milk-allergic infants.

Other approaches to the treatment of food allergies are not prophylactic. Immunotherapy (e.g., allergy shots or sublingual food drops) is considered experimental and controversial therapy for food allergies. Other dietary approaches such as rotation diets are similarly controversial.

Pharmacological approaches can be used to treat the symptoms of allergic reactions. In particular, epinephrine (also known as adrenalin) is prescribed for individuals who experience life-threatening food allergies. Its early administration after inadvertent exposure to the offending food can be life-saving for such patients. Antihistamines are another group of drugs used frequently to counteract the symptoms of allergic reactions, yet they counteract only those symptoms associated with histamine and not those attributable to other mediators.

Date added: 2022-12-11; views: 736;