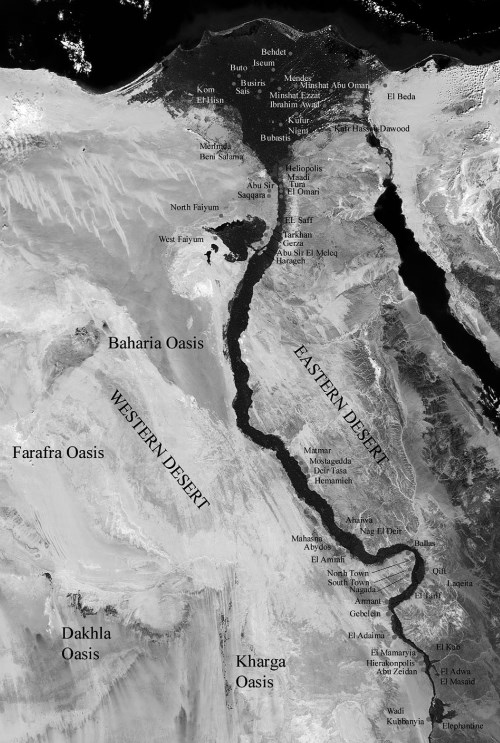

Egypt, Pre-Pharaonic. Location map of principal Predynastic sites in Egypt

Communities settled along the banks of the Nile from the border with Nubia to the shores of the Mediterranean were brought together 5000 to 4700 years ago to form a single state under the rule of powerful kings, who were later referred to as ‘Pharaohs’. The Egyptian state depended on the agricultural productivity of the Nile Valley and the Delta. Agriculture was introduced in Egypt 2000 years earlier (see Plant Domestication).

The earliest food-producing (Neolithic) communities in Egypt were established on the western margin of the Delta at Mermida Beni Salama and around the Faiyum Depression (Figure 1 ). These sites indicate that wheat and barley were cultivated and that domestic sheep, goat, and cattle were herded. Except for a breed of cattle which was ‘kept’ in the Eastern Sahara around Nabta Playa and Bir Kisseiba, domesticated species of animals and plants were introduced from Southwest Asia.

Figure 1. Location map of principal Predynastic sites in Egypt

Initially, a small community sheltering in flimsy huts, the inhabitants of Merimda Beni Salama developed into a well-organized community living in a large village with mud huts. Graves were found with the settlements, but grave goods were rare. The repertoire of the last occupation at Merimda which lasted until about 4100 BC included polished dark red/black pottery, bifacial tools, figurines, and other bone, ivory, and shell items. At El-Omari, near Helwan, burials included an individual with a scepter and valuable grave goods, perhaps indicative of the rise of local paramount chiefs.

In Upper Egypt, the earliest food-producing communities are in the Badari region where small encampments, probably of herders, date back to 4400-4200 BC. These sites signal the beginning of the period commonly referred to as the Predynastic. The Badarian Early Predynastic sites contain a variety of brown, red, and occasionally black pottery with a shiny, burnished surface with ripples. This Rippled pottery is produced from very fine untempered Nile silt.

The Badarian pottery is a variant of a burnished pottery present in Late Neolithic sites of the Egyptian Sahara. Badarian personal items included hairpins, combs, bracelets, and beads made out of ivory and bone. Palettes were also found. A variety of clay and ivory figurines are also represented in the Badarian. A component of the Badarian is known as the ‘Tasian’ which perhaps represents greater affinities with highly mobile groups that moved between Nubia and the Assyut region via desert routes.

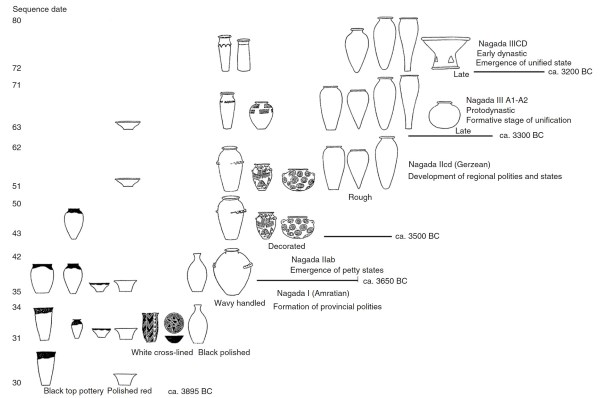

South of Badari, in the Nagada region (between Danfiq and Ballas), are numerous Middle and Late Predynastic village settlements and remnants of two towns (North Town and South Town) as well as extensive cemeteries dating from 3800 to 3500 BC. Two archaeological units on the basis of pottery types are identified during that period (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Changes in the material, form, and decoration of Predynastic-Early Dynastic pottery have been used to generate pottery types and pottery assemblage zones. The absolute chronology of the assemblage zones, Nagada I, II, and III (called after ‘Nagada’, also known as ‘Naqada’ in Upper Egypt), span the period from c 3950 to c. 3000 BC. This period was characterized by significant political transformations that led c. 3200 BC to the emergence of a unified Egyptian state

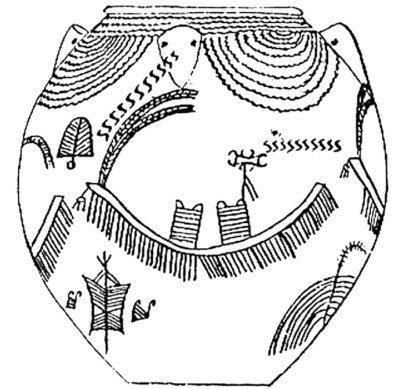

The earliest ceramic assemblage zone called Naqada I (or Amratian) is generally characterized by a high frequency of Black-Topped Polished Red and White Cross-Lined pottery. This zone marks the Middle Predynastic dating from 3950 to 3650 BC. It was succeeded by the Late Predynastic Naqada II (also known as the Gerzean), dating from 3650 to 3300 BC, which is characterized by Rough pottery, and marked by the presence of Decorated and Wavy-Handled pots (Figure 3). Naqada I and Nagada II sites extend from Badari to Hierakonpolis.

Figure 3. A diagnostic type of pottery (Decorated) that became common in Nagada II (Gerzean). Painted in red over a buff background, the ‘decorations’ show a variety of motifs and themes. Many, as in the case of this pot, show zigzag lines suggestive of water, trees, and boats with many oars and two cabins. These pictorial representations reveal the first steps toward writing and are most probably symbolic of religious beliefs concerning the journey from the land of the living to the land of the dead. Source Petrie WMF (1974) Prehistoric Egypt, London: Aris and Phillips

The majority of Predynastic sites in the Nagada region belong to Naqada I. The sites range in size from a few thousand square meters to 3 ha. They represent overlapping occupations of scores of huts in small villages and hamlets in a string along the edge of the former floodplain. Small postholes and the wooden stub of a post suggest flimsy wickerwork around a frame of wooden posts. The abundance of rubble and mud clumps indicates that many dwellings were constructed from local Nile mud and desert surface rubble.

The houses contained hearths and storage pits. In some cases graves were dug into the floor of houses. Trash areas were interspersed with domestic dwellings. The houses included animal enclosures as indicated by thick layers of dung. The faunal remains indicate exploitation of cattle, sheep/goats, and pigs. Hunting was limited. However, fishing and fowling were important.

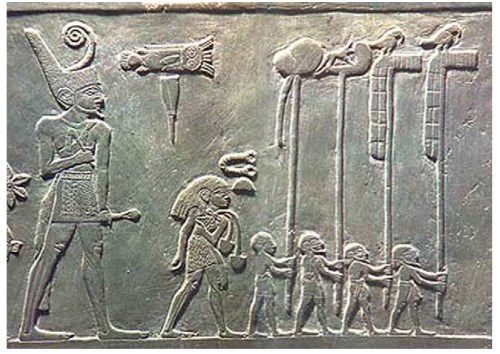

Nagada I and II sites in Upper Egypt reveal pronounced progressive transformation of social organization and increasing complexity (Figure 4). The tombs yielded a rich variety of grave goods including copper objects, flint knives, amulets, stone vessels, pendants, hairpins, combs, and slate palettes. Only a few graves contain large numbers of special goods, and the distribution of grave goods indicates the emergence of tiered social hierarchy by Nagada I. By Nagada II, the elite segregated their burial grounds from those of the commoners. Their graves were larger and well-endowed with grave goods (see Social Inequality, Development of).

Figure 4. Detail from Narmets palette (now in the Egyptian Museum, Cairo) showing Narmer, the first or second king of a unified Egypt, in a ceremonial procession. The procession is led by standard-bearers who may represent the domains or main allies of the king. The palette has been interpreted in many ways, but is most likely symbolic of the emergence of a powerful king who commands the Delta and Upper Egypt. The palette also shows well-developed hieroglyphic signs as a part of a writing system that emerged 200years earlier

The rise of a local elite was embedded in a religious ideology linked with mortuary rituals as indicated by the standardization of the placement of the dead who were buried in a flexed position with heads to the south facing west. However, there were regional differences in the prevalence of this orientation. The iconography of Nagada II pottery and a variety of figurines from mud and vegetable substances suggest that the incipient ideology included notions of female-male duality associated with concepts of life, death, and apparently life after death.

Centered on grave goods and funerary rituals, the ideological technology of the emerging elite promoted trade within and beyond Egypt for elite mortuary goods. Hierakonpolis in the south was a conduit for trade with Nubia, whereas Maadi and later Buto in the Delta provided trade links with Southwest Asia.

During the period when the Nagada I and II pottery types were emerging and spreading in Upper Egypt, communities in the Delta shared a distinct pottery assemblage, referred to as the Maadi-Buto Horizon. By the middle of the Late Predynastic, the pottery types common in Upper Egypt became prominent in the Delta. It is unlikely that this is an indication of a population replacement or a military conquest.

It is most probably a result of the adoption by the Delta elite of the funerary ideology and practices of Upper Egypt with its intricate rituals, elaborate burials, and fancy grave goods. This was facilitated by the close trade links between the two main trade centers of Hierakonopolis and Buto and by the use of boats bypassing overland donkey routes.

It appears that the Middle Predynastic was a period of incipient state formation on a regional scale, with at least two prominent states or petty kingdoms namely Hierakonpolis and Nagada in Upper Egypt, and perhaps several town-principalities in the Delta. By about 3300 BC, Hierakonopolis seems to have extended its power over Nagada so that it began to dominate the area north of Nagada from a new stronghold at Abydos, establishing a far more suitable strategic geopolitical position within a shorter distance from Middle Egypt and the Delta than that of Hierakonpolis at the southern border of Egypt.

Considering the narrow floodplain at Hierakonpolis and access to a more extensive floodplain north of Abydos, the leaders of Hierakonpolis would have buffered themselves from droughts which appear to have become more prevalent as Nile flood discharge began to diminish c. 3300-3200 BC, coincident with the transition to hyperarid conditions in the Eastern Sahara. It is also likely that the residents of the desert regions surrounding the Nile Valley and the Delta who struggled through the transition from wetter conditions before 6200 to 4100 BC might have been forced to raid the prosperous villages in the Nile Valley and the Delta giving rise to occasional skirmishes.

This would have provided the elite with another legitimizing opportunity - the portrayal of the chiefs as ‘warriors’ smiting enemies. This was expressed in the use of the mace-heads as symbols of authority and in the depiction of battle scenes on commemorative ceremonial palettes. There is also the possibility that some of the ferocious desert warriors were integrated within settled agrarian communities.

Given the benefits to small communities either for defense or food security against droughts and food shortages, and for the tendency of elites to aggrandize and strengthen their position through bigger tombs, more and more costly grave goods of rare materials and better artisanship, a trend was set for large political entities like the expanding Hierakonpolitan ‘kingdom’ to get bigger by annexing small polities. This perhaps demanded no or little use of force or intimidation since an alliance with a larger power may be conceived as beneficial to small polities.

The transition from the level of regional complexity to that of multiregional complexity, extending from Hierakonpolis to Abydos and perhaps beyond, made it imperative to co-opt regional chiefs and rulers within the demonstrative structures of the expanding kingdom thus attenuating the grip of kinship as a social bond among the elite. This also necessitated syncretic religious ideologies that incorporated a pantheon of regional and local deities. Alliances may have also been fostered by inter-regional royal marriages. This may explain the important role of royal wives in the development of the Egyptian state and the role of women in the ideology of kingship.

Royal wives were perhaps the link between the king and his allies, and their position as mothers of future kings consolidated their role, within religious ideology, as divine mothers. Although the bull might be a more likely religious entity in hunting societies, the cow is perhaps equally important, or even more important, in a herding community. Cow burials were already manifest among cattle keepers of the Eastern Sahara before 5000 BC. Narmer’s palette depicting the king as a bull is surmounted by two large cow heads.

During this formative stage of Egyptian kingship, writing was developed within a ritual, royal context and is attested on ivory labels predating Narmer’s palette which carries phonetic signs of his name. Narmer was succeeded by Aha who together with his successors began to lay the foundation of a unified Egyptian state heralding the Dynastic Period.

They established an administrative capital at Memphis close to their Delta allies while maintaining Abydos as a religious capital and a royal burial ground. The unification suffered periodic setbacks, especially during the Second Dynasty. By the time Zoser established his reign, he was able to build a monumental step- pyramid of unprecedented dimensions as his royal tomb, a clear indication that a mighty Pharaoh ruled over a state society with an elaborate administrative structure.

Further Reading: Adams B (1988) Predynastic Egypt, Aylesbury: Shire Egyptology 7. Bard K (1999) Predynastic period, overview. In: Bard K (ed.) Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt, pp. 23-30. London: Routledge.

Hassan FA (1988) The Predynastic of Egypt. Journal of World Prehistory 2: 135-185.

Hassan FA (1999) Epipalaeolithic cultures, overview. In: Bard K (ed.) Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt, pp. 15-16. London: Routledge.

Hendrickx S, Friedman RF, Cialowicz KM, and Chlodnicki M (eds.) (2004) Egypt at its Origins. Studies in Memory of Barbara Adams. Brussels: Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta. Peters Publishers.

Maisels CK (1999) Early Civilizations of the Old World. London: Routledge.

Midant-Reynes B (2002) The Prehistory of Egypt. Oxford: Blackwell.

Wenke RJ (1999) Neolithic cultures, overview. In: Bard K (ed.) Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt, pp. 17-22. London: Routledge

Date added: 2023-11-08; views: 851;