Arranging the Species. Biology

The argument over spontaneous generation was, in a sense, one over the problem of classifying life; whether to place it as eternally separate from nonlife or to allow a series of gradations. The seventeenth and eighteenth centuries saw, also, the development of attempts to classify the various forms present within the realm of life itself, and this was to serve as the start of an even more serious controversy than the one over spontaneous generation, a controversy that was to reach its climax in the nineteenth century.

To begin with, life forms can be divided into separate species, a word that is very difficult, actually, to define precisely. In a rough sense, a species is any group of living things that can mate freely among themselves and can, as a result, bring forth young like themselves which are also capable of mating freely to produce still another generation and so on. Thus, all human beings, whatever the superficial differences among them, are considered to belong to a single species because, as far as is known, men and women can breed freely among themselves regardless of those differences. On the other hand, the elephant of India and the elephant of Africa, although they look very much like the same sort of beast to the casual eye, are separate species, since a male of one group cannot mate and produce young with a female of the other.

Aristotle had listed five hundred species of animals, and Theophrastus as many species of plants. In the two thousand years since their time, however, continued observation had revealed more species and the broadening of the known world had unloosed a veritable flood of reports of new kinds of plants and animals that no ancient naturalist had ever seen. By 1700, tens of thousands of species of plants and animals had been described.

In any listing of even a limited number of species, it is very tempting to group similar species together. Almost anyone would naturally group the two species of elephants, for instance. To find a systematic method of grouping tens of thousands of species in a manner to suit biologists generally is no easy matter, and the first to make a major attempt in this direction was an English naturalist, John Ray (1628-1705).

Between 1686 and 1704, he published a three-volume encyclopedia of plant life in which he described 18,600 species. In 1693, he prepared a book on animal life that was less extensive but in which he attempted to make a logical classification of the different species into groups. He based the groups largely on the toes and teeth.

For instance, he divided mammals into two large groups: those with toes and those with hoofs. He divided the hoofed animals into one-hoofed (horses), two-hoofed (cattle, etc.), and three-hoofed (rhinoceros). The two-hoofed mammals he again divided into three groups: those which chewed the cud and had permanent horns (goats, etc.), those which chewed the cud and had horns that were shed annually (deer), and those which did not chew the cud (swine.)

Ray's system of classification was not kept, but it had the interesting feature of dividing and subdividing, and this was to be developed further by the Swedish naturalist, Carl von Linn (1707-78), usually known by the Latinized name, Carolus Linnaeus. By his time, the number of known species of living organisms stood at a minimum of 70,000; and Linnaeus, in 1732, traveled 4600 miles hither and yon through northern Scandinavia (certainly not a lush habitat for life) and discovered a hundred new species of plants in a short time.

While still in college, Linnaeus had studied the sexual organs of plants, noted the manner in which they differed from species to species, and decided to try to form a system of classification based on this. The project grew broader with time and in 1735, he published System Naturae, in which he established the system of classifying species which is the direct ancestor of the system used today. Linnaeus is therefore considered the founder of taxonomy, the study of the classification of species of living things.

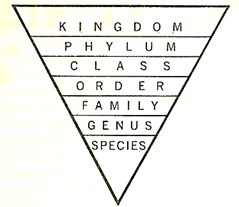

Figure 1. Diagram showing, in descending order, the main classifications—from Kingdom to Species—into which living things are placed by taxonomists

Linnaeus systematically grouped similar species into "genera" (singular, "genus," from a Greek word meaning "race"). Similar genera were grouped into "orders," and similar orders into "classes." All the known animal species were grouped into six classes: mammals, birds, reptiles, fishes, insects and "vermes." These major divisions were not, actually, as good as those of Aristotle two thousand years before, but the systematic division and subdivision made up for that. The shortcomings were patched up easily enough later on.

To each species, Linnaeus gave a double name in Latin; first the genus to which it belonged, then the specific name. This form of "binomial nomenclature" has been retained ever since and it has given the biologist an international language for life forms that has eliminated in-calculable amounts of confusion. Linnaeus even supplied the human species with an official name; one that it has retained ever since—Homo sapiens.

Date added: 2022-12-11; views: 777;