Intervening Variables

The mounting stress of HIV infection may cause infected people to appraise their world as uncontrollable, resulting in their inability to deal with additional challenges and in a greater likelihood of depression, substance use, risky sexual behaviors, and poor self-care. This sequence is more likely among those with inadequate coping skills and sustained social support losses. Several psychosocial factors, such as perceived loss of control, maladaptive coping strategies, and social isolation, have been related to impaired immune functioning in a wide variety of healthy populations.

These processes (and intervention-associated changes in these processes) may be associated with immunological alterations in HIV-infected people. Recently, studies have demonstrated a possible link between these psychosocial processes and the physical course of the infection.

Perceived loss of control. Various stressors, especially those viewed as uncontrollable, have been associated with decrements in immune function in healthy people. Some of these are particularly prevalent among HIV-infected people attempting to cope with their illness and include bereavement, the stress of being a caregiver for a loved one with a terminal disease, and divorce or break-up. Among HIV+ men, those with more cumulative stress had faster disease progression over a 9-year period. Some work suggests that stress may affect immune declines in HTV+ people by disrupting sleep.

Coping strategies. Coping strategies, such as active coping, active confrontation, ‘‘fighting spirit,’’ and denial, have been related to changes in physical health during HIV-infection. The use of active coping was associated with decreased symptom development in HIV-infected gay men. A ‘‘fighting spirit’’ coping strategy also predicted less symptom development, whereas denial coping predicted a greater number of HIV-related symptoms over a 12-month period.

Other coping strategies such as avoidance and denial have also been associated with declines in immune function in HIV+ men. During the stressful period of HIV antibody testing, greater avoidance of distressing AIDS-related thoughts predicts greater anxiety, depression, and confusion as well as lower lymphocyte proliferative responses and NKCC after notification of positive serostatus. Increases in the use of denial during the postnotification period also predict a faster progression to AIDS over a 2-year follow-up period.

In another cohort of HIV+ men, greater use of denial predicted faster progression to AIDS over a 7.5-year period. Gay men with AIDS who used a strategy called realistic acceptance showed a shorter survival time than those not endorsing this strategy. Realistic acceptance appears to reflect excessive rumination and focus on HIV-related matters, almost to the exclusion of many other facets of life. It may be that while denial is maladaptive and predictive of poorer health outcomes, obsessing and ruminating about the disease may also have negative health ramifications.

Newer work has produced evidence that greater use of distraction as a coping strategy predicts a slower subsequent course of disease over a 7-year follow-up period. Distraction here reflects an effort to focus on living and pursuing activities that are meaningful rather than denying the existence of the infection or refusing to focus on it excessively. This sort of balance between acceptance and nonrumination has also been identified as a common trait of those who are long-term survivors of HIV infection and AIDS.

Social isolation. HIV-infected people face a variety of stressors and challenges that they must continually negotiate in an effort to deal with the potentially overwhelming psychological and physical health consequences of their illness. Stigmatization, alienation from friends and family, increased reliance on medical personnel, social disconnectedness, and gradual deterioration of physical health status and immune functioning may leave these individuals feeling socially isolated. Social resources have been found to buffer the negative physical and psychological effects of major life-threatening events.

Low social support availability predicts a faster decline in CD4 counts over a 5-year period among HIV-infected men with hemophilia. Larger social network size and greater informational support provided by that network predict greater survival time in HIV-infected men but only among those with AIDS. Greater perceived social support also predicts a slower progression of disease in initially asymptomatic HIV+ gay men over a 9-year period. It remains to be demonstrated whether actively intervening to increase the quality of HIV-infected people’s social support influences their long-term psychological adjustment, immune functioning, physical health status, and subsequent disease progression.

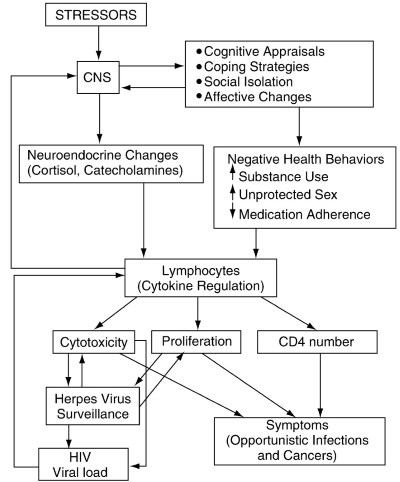

To summarize, HIV infection is a chronic disease often associated with severe psychosocial and physical stressors, which can potentially overwhelm those infected in a number of domains. The stressors that encompass HIV and AIDS impact the way in which those infected appraise day-to-day situations, choose coping strategies, acquire support, and deal emotionally with stressful events in their lives, which in turn can alter stress hormones as well as influence their ability to engage in healthy behaviors.

Figure 1. Model relating stressors, psychosocial factors, neuroendocrine changes, health behaviors, immune status, and disease in HIV infection. CNS, central nervous system; CD4, T-helper lymphocytes; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus

These processes can then lead to alterations in immune system functioning, which may have repercussions for the development of symptoms and increased HIV viral load. Figure 1 displays the interconnectedness of these multiple factors in HIV disease.

Date added: 2024-08-23; views: 423;