Homeric Epics. Detailed history

According to one view, the author Homer wrote two works, the Iliad and the Odyssey, in about 800, describing events that had occurred three to four centuries earlier. The other view is that a series of authors composed two epic poems handed down through oral tradition until finally coalescing into these two works. Modern scholars also believe that although the two poems were composed at about the same time, they were probably written by two different authors, perhaps one named Homer, the other unknown. The debate, however, is far from over and will probably never be settled.

In antiquity, Homer was said to be a blind poet from Ionia or the western coast of Turkey. Other ancient authors have it that he was from Chios and was a wandering poet. While these stories about Homer are fictitious, the ancients made Homer into a semidivine person who understood society, politics, and warfare.

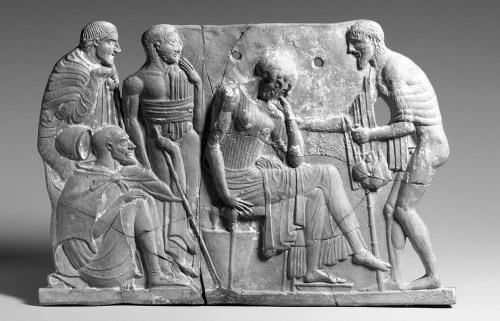

Odysseus returning to Penelope. (The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Fletcher Fund, 1930)

The poems are a mixture of Ionic and Aeolic dialects and contain words, phrases, and morphology from different centuries, with eastern Ionia dominating. The poems were transmitted orally at first, and many of the phrases show examples of stock formulas and words, often repeated, such as words for war, honor, individual combat, and lineage. The name Homer then should be seen more as a way to celebrate the culmination of the Iliad and Odyssey being written down rather than an individual writer who composed the final version.

The two works were the earliest textbooks for ancient students. In particular, the Iliad was used more by teachers in antiquity, especially during the Hellenistic and Roman eras. His works were used by succeeding generations to describe the education and philosophy of the pre-Classical Greeks, with Homer even being seen as a philosopher. In the modern period, scholars hold that the two poems were not produced by the same author due to extensive differences in the treatment of the gods, ethics, geography, terminology, and politics. Each poem, however, shows unity within itself, indicating that they were probably each created as a distinct entity rather than merely a compilation of smaller poems put together to tell a story.

Although in antiquity, the audience thought that Homer was an eyewitness to the events described, it is now known that the differences between the two works and the events afterward show that the final authors lived several centuries after the Trojan War and relied on a tradition of oral stories passed down. In the pre-twentieth century, many individuals even doubted whether the events took place at all, but Heinrich Schliemann in 1873 showed that there was indeed a Troy in the area described by Homer. While Schliemann’s archaeological dig may have misidentified the particular ruin, it has been shown that a series of wars took place at the site over several centuries, with some corresponding to the period from 1250 to 1000.

The current theory is that the Iliad was written shortly before the Odyssey, with Homeric formulas preserving earlier materials than the contemporary poems. They were written in heroic hexameter poetry or unrhymed dactylic hexameter. This type of poetry used quantitative meter rather than stresses. The dactylic hexameter has six feet, where each foot would be a dactyl composed of one long and two short syllables, although with the spondee (or two stressed or long syllables) in place of the dactyl. This system helped the poet extemporize due to a continual repetitive structure, and the poems could be memorized based upon the story and structure of the language.

The Iliad concerns itself with war, particularly the fighting that took place before the wall of Troy. Multiple stories are interwoven in the poem, telling about events that occur over only four days in the tenth year of the war. Taking its name from Ilion, another name for Troy, the poem is about the “wrath of Achilles” and how the Greek leader Agamemnon avenged his honor. During the war, a plague descends upon the Greek army due to the daughter of a priest of Apollo, Chryseis, being taken by the great king. If he returned her, it is said, the plague would be lifted. Agamemnon assents, but he takes in her place Briseis, Achilles’s slave- concubine. Achilles refuses to accept this affront and does not participate in the fighting, so the Greeks are bested.

Although Agamemnon attempts to make amends, Achilles continues to brood. When the Trojans attack and burn the Greek ships, Achilles’s friend Patroclus puts on Achilles’s armor, with Achilles’s blessing, and goes to meet Hector, prince of Troy. Hector kills Patroclus, thus bringing Achilles out of his despair; he meets the Trojans, killing Hector and then abusing the corpse by tying it to his chariot and dragging it through the dust. The poem ends with the funeral games of Patroclus and the Trojan king Priam begging Achilles for the body of Hector. After his anger subsides, Achilles pities the old king and allows the body to be returned.

The poem also describes the court life of Troy. The aged monarch Priam and his wife, Hecuba, witness so many of the Trojan warriors and their own sons being killed (especially their favorite son, Hector) in battle. The poem also shows the interplay between Hector and his wife, Andromache, with one scene where Hector, readying for battle in his full armor, frightens his young son when he wears his helmet. The poem also explains the story of Helen, wife of the Greek king Menelaus who was taken by Paris, Hector’s brother, to start the war.

The poem originally shows Helen willingly leaving Menelaus for Paris, but now she despises the Trojan prince. The poem includes various other subplots that contribute to the background of the war. One of the most important sections for Greek development includes the catalogue of Greek Ships and catalogue of Trojan forces, which occupies most of Book 2 of the Iliad describing the forces on both sides engaged in the great war. This section provides an understanding of historical powers both in the eighth century, when the work was written, and the thirteenth century, when the war was supposed to have taken place.

The differences in the poem show itself in a variety of fashions. For example, the warriors in the poem are cremated, as was common in the eighth century, not entombed in shaft graves as in the Mycenaean period. The weapons described by Homer are forged of iron, which was inexpensive in his time but costly in Mycenaean times, when bronze still dominated. On the other hand, Homer describes the cup of Nestor, which was decorated with Minoan art motifs found in Mycenaean sites, and a helmet that had gone out of style before Mycenae had even fallen. It is in the Catalogue of Greek Ships that one finds the greatest difference between the Mycenaean and Homeric periods.

The Odyssey, like the Iliad, is written in twenty-four books that cover the wanderings of Odysseus after the Trojan War. While the actual time in the poem is only the last six weeks, Odysseus relates his story and adventures from even earlier. After Troy’s destruction, Odysseus sails to Thrace and engages in piracy; then to the Lotus-Eaters, where his crew becomes placid due to eating the lotus; and then to Italy and the land of the Cyclopes. Here, he kills Polyphemus, the son of Poseidon, earning the sea god’s enmity. He and his crew are then entertained by Aeolus, who gives him a bag filled with all of the adverse winds so he could sail home without incident, but his crew opened the bag since they believe it holds treasures.

This act drives his ships to the land of Laestrygones, cannibal giants who destroyed eleven of his twelve ships; and then to Aeaea, where the witch Circe turned Odysseus’s men into pigs. After Odysseus has forced Circe to restore his men by threatening to kill her, she instructs him to go to the underworld to consult Teiresias about how to return home. There, he meets his mother and other heroes, including Achilles. Teiresias tells him how he would be able to return.

Odysseus and his crew then sail past the Sirens and between Scylla and Charybdis mythological creatures which destroyed ships in the Strait of Messenia off Sicily, probably rocks and a whirlpool, respectively, and then to Thrinacia, where his crew kills the sacred cattle, prompting Zeus to destroy his ship and crew. Odysseus then makes it to Ogygia, where Calypso takes care of him for seven years before being ordered by the gods to set him free. Odysseus next sails to Scheria, where he is found by Nausicaa, the daughter of King Alcinous. He finally returns home to Ithaca, where his palace has been invaded by suitors aggressively wooing his wife, Penelope.

During the time, Odysseus has been gone (ten years at Troy and ten years wandering), Penelope has been true. Raising their son, Telemachus, she has been the model of wifely virtue. When Odysseus does not return after the war, she is pressed to marry again. She is able to put off the request for a while by indicating that she had to finish the burial cloth for Odysseus’s father, Laertes, before considering remarriage. Every night she undoes the work of the day until her deception is discovered. Telemachus visits Nestor at Pylos and Menelaus and Helen at Sparta, attempting to discover where his father is. With Odysseus returning as a beggar, and after being abused by the suitors, he reveals himself to Telemachus.

Penelope is instructed to give a task to the suitors—whoever can string Odysseus’s bow and shoot an arrow through twelve ax heads can wed her. After all of the suitors fail, the old beggar asks and successfully strings the bow and shoots the arrow. He then proceeds with Telemachus’s help to kill all of the suitors and hang all of the women of his household who had become their lovers. He finally convinces Penelope that he is her husband by describing their wedding bed. Athena prevents any further blood feud by stopping the families of the suitors from attacking to seek revenge.

The poems relate the society of both the Mycenaean world and the Dark Ages. Social structures exist but are often at variance. For example, the Iliad refers to Agamemnon as “Wanax,” a term for “king” not used much in the Dark Ages. The fighters in the Iliad use chariot to bring them to the battlefield like taxis but the chariots do not play any part in the actual battle. The Greeks use the spear as a throwing weapon, even though it was used as a thrusting weapon during the Mycenaean period. These differences stem from the fact that the poems underwent dramatic changes during the 300 years of oral tradition before being written down.

There are also differences such as terminology, the use of aristocratic councils in the Odyssey, and the role of the gods. In the Iliad, the gods are at odds with each other and take sides, while in the Odyssey, they act more as spectators, with the exception of Poseidon and Athena. The Homeric Age, as related through the Iliad and the Odyssey, describe the continual evolution of Greek society from the Heroic Age of the Mycenaean through the Dark Ages before the creation of the polis. They describe the lives of kings and the emerging aristocrats, rooted in military conflict.

Date added: 2024-09-09; views: 487;