Developing the Skills of Hope

The issues surrounding poverty-driven marginalization are complex and without singular solution. Yet, there are actions that teachers can take to help students position themselves for success. Dixson, Worrell, and Mello (2017) have found that hope— having something to look forward to and tangibly work toward—is associated with better engagement and curiosity in the classroom and higher academic achievement among students experiencing poverty. Similarly, Seligman, Railton, Baumeister, & Sripada (2016) argue the importance of anticipating and evaluating future possibilities as a means for guiding thought and action, going so far as to describe the practice as the cornerstone of human success.

Brown (2010) defines hope as a way of thinking or a cognitive process. In this definition, hope is not an emotion but a set of action steps wherein students learn to set realistic goals, figure out how to achieve those goals, and learn to persist despite challenges (Snyder, 2000). In many ways, these processes parallel those used by composers as they engage in creating new music. As such, music teachers can help students learn the strategies that contribute to the development of hope as they engage in composition projects.

Identifying and Prioritizing Goals. Goal identification and prioritization are strategies that students can use to discern what is important to them and what they wish to achieve. The practice of naming and numbering goals can feel empowering to students as they are situated within educational institutions where goals are typically controlled by adults through predetermined curricula and practices that focus on students as a collective. Composition provides teachers with an opportunity to respond to each student’s musical goals. Centering the student in this partnership is mission-critical as many students are highly motivated to achieve goals that they establish for themselves, but quickly lose interest in the goals set by others.

Teachers can help students become drivers of their own success by inviting them to create a list of “I want” goals. These might include, “I want to write a country song” or “I want to create beats for my friends,” or similar goals that are positive and forwardlooking. Students can then be invited to prioritize their goals. This process helps students focus on what they want to achieve and limits potential distractions from stealing their focus and energy. Students also benefit from considering sub-goals. Ask them to think about what they will need to do to accomplish each goal.

Goal Analysis and Prioritization. It may be very easy for some students to create a lengthy wish list of goals. Such lists can be overwhelming and exhaust students before they set to work. Adding to this sense of overload may be the impression that goals are all-or-nothing propositions that must be accomplished all-at-once. This type of thinking is the result of the have-or-have-not dichotomy of despair. To address these misconceptions, teachers can guide students to consider their number 1 goal in detail. Students can be encouraged to consider what skills they might need to learn to achieve their goal and how the goal might be approached over several smaller steps. Students should also identify how they will know when each step toward their goal has been successfully completed and when their goal has been achieved. This allows students to acknowledge small victories and maintain the motivation needed for forward momentum.

Obstacle Framing. Like life itself, composition lessons often feature challenges and obstacles that can be frustrating. To remain engaged when work becomes hard, students need to learn that there may be multiple approaches to tackling problems and challenges. This counters the notion that encountering an obstacle signals defeat.

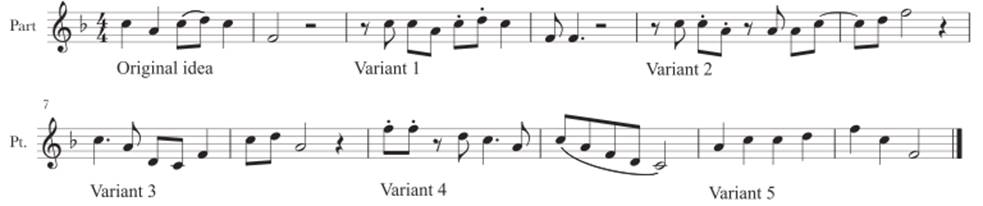

In creating music, composers often wrestle with finding, and then developing, their central idea. Without the tools to move forward, they may become stuck in a cycle of repetition that leaves them dissatisfied. The solution to this challenge lies in a combination of brainstorming and radical editing. Students can be encouraged to take their initial idea and sing it, play it, or write it in as many different ways as they can imagine (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2. Idea development

Once they have amassed several or even dozens of ideas, they can try each one within the context of the music they have already made up. This process helps students learn that the barriers they encounter are not signs that they lack talent, but opportunities to think differently, see things anew, and try other options. From this process, they learn that success is not found in avoiding challenges, but in figuring out how to address the challenge and move on.

Balancing Help and Self-Reliance. It is tempting for teachers to step in and offer quick fix solutions when students experience frustration in the composition process. While it is certainly appropriate for teachers to offer multiple solutions for students to test as a pathway forward, the teacher- as-fixer model tends to insert the teacher’s artistry into the student’s work. Ultimately, this disempowers and possibly disenfranchises the student composer. What may most benefit students in their moment of frustration is a strategy for discovering problemsolving tools.

In the composition classroom, music educators can set the stage for the discovery by including projects that feature the teacher facilitating compositions by the whole class. This setting allows teachers to engage students in the processes of idea generation, testing, and selection. They also can invite students to evaluate the affective potential of musical gestures and ask questions that guide revision. Within this collaborative setting students directly experience the enactment of a successful composition process. These experiences then become stories that students can revisit when they are stuck. Students might be prompted with questions such as, “How did we decide which idea to use?” or “How did we transition from the beginning to the middle section of the piece?” Revisiting previous successes to discover process strategies prepares students to be self- reliant, which in turn builds their self-confidence.

Positive Self-Talk. Self-talk is a powerful tool that students can use to acknowledge their progress. Physical educators have noted how the use of positive self-talk can motivate students and lead to higher levels of achievement (Ada, Comoutos, Karamitrou, & Kazak, 2019). Recently, Ohki (2020) researched similar strategies in music training and found that musicians who reinforce achievement with self-talk attain higher levels of success. Similar findings have been noted for students with learning disabilities (Feeney, 2022) and found to improve motivational resilience for middle school learners, too (Flanagan & Symonds, 2021).

As students compose, it is important that they acknowledge to themselves both minor victories (e.g., “I found the right note to end this line”) and milestones (e.g., “I finished this verse”). Teachers can help students develop check sheets to facilitate this practice. Lists might include items such as: outlined the form of the piece, completed the A- section, built the beat for the chorus, created a melodic theme and three variations, and so on. Each milestone is an opportunity for students to recognize the completion of one step toward their goal. As Brown (2010) notes, taking time to note achievements is critical in the development of hope as students who use positive self-talk are more likely to reach their goals than students who loop negative messages.

Date added: 2025-03-20; views: 261;