Exercises for Novice Composers

Choral teachers become experts at extracting exercises from repertoire for warm-up exercises to make learning the repertoire easier. There is also a treasure trove of composition exercises to benefit students, from developing the voice to learning about chords and counterpoint.

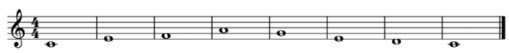

Exercises with Counterpoint.Starting with a simple cantus firmus (c.f.), the teacher can provide simple rules to first species counterpoint and have students experiment in sections (or as individuals over a section) to produce a vocal line over the c.f. (Figure 31.1). Some basic rules are to (1) begin and end on unison, octave, or fifth, (2) notes can only move with the cantus firmus (in whole notes), (3) avoiding parallel fourths and fifths, (4) avoid singing the same intervals more than three times in a row, (5) attempt to sing in contrary motion to the c.f., particularly when the c.f. skips (Mann, 1965).

Figure 31.1. Example of a species counterpoint cantus firmus (Chase, 2020). Accessed https:// hellomusictheory.com/learn/species-counterpoint/

A teacher can record the c.f. on piano in a DAW program and provide written notation. Students should notate a countermelody and then perform on a second track, then listen and reflect on what they heard. Alternately, the teacher can teach students to sing the c.f. and some students then take turns singing the c.f. while other students improvise a countermelody line individually. For improvisations, teachers can tell students to follow rules 1 and 2. In hearing each other, students will discover that it sounds different when one avoids singing parallel to the c.f., especially parallel fourths and fifths. They will also notice that contrary motion is more interesting than parallel motion. Once they have completed this exercise, they will be able to search through familiar repertoire to find which counterpoint rules the composer followed and discuss reasons for deviating from traditional counterpoint rules. An exercise like this gives students practice in self-awareness by developing their musical listening and practicing their skills at describing what they hear with nonjudgmental language.

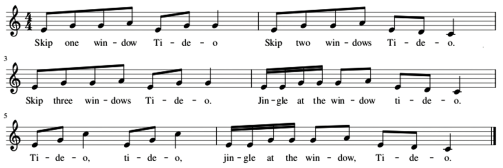

For another exercise, students should learn to sing a simple folk song like “Tideo” (Figure 31.2). Once learned, the song should be analyzed for the interval size and directions, tonal center, and key. Next, students should discuss ideas about some emotional or sensual quality they might want to convey about the lyrics and melody through a countermelody or descant. They should then explore a variety of ways to translate their intent. This exercise might be completed in sections, with each section working together to notate and record themselves singing the descant while other sections sing the melody. It will benefit everyone to hear each other’s descants because they will have the chance to hear a variety of approaches and make their own decisions about what conveys a specific intent. An exercise like this will engage students in self-management skills because they begin to think about what they want to communicate and how to communicate effectively through music. For a first exploration into this exercise, it may be best to avoid assessing for success or failure but allow students, instead, to enjoy creating and sharing their reflections on the process of decision-making.

Figure 31.2. The folk song, “Tideo”

Exercises with Chord Progressions.In planning chord progressions, the teacher can provide some simple tools to work with. Students should learn to name key signatures and have a chart of chords with Roman numerals to reference as they work. They should also have access to letter names and notation for major and minor chords so they can easily see, for example, that the notes of any type of C chord are C, E, and G. The chart can include examples of adding a seventh scale degree to a chord and names of first and second inversions. The example below will provide steps for this exercise.

For a first exercise, the teacher can have students analyze chords that accompany an arrangement of a folk song. The students would first listen to a recording of an arranged folk song, like the SATB arrangement of “Now Is the Cool of the Day,” written by Jean Ritchie, arranged by Peter and Jon Pickow, and adapted by James Erb (1971), taking notes about the sense of flow, weight, direction, and speed as the piece progresses (teacher may have each section tracking one holistic element) on scrap paper. Following a whole-class discussion of what students heard and reasons they posit for the composer’s decisions, the teacher should provide the chord progression and melody for a section of the piece for analysis.

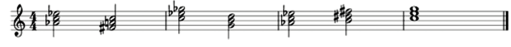

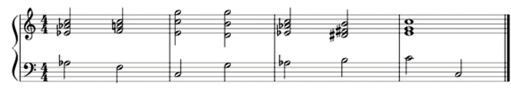

Figure 31.3 shows a condensed score for the opening voices of the chorus. Here, the teacher should have the students name the notes for each measure vertically to arrive at the chords by letter name. They should then review key signatures so they can name the chord functions. They can then discuss the reason that James Erb would include the dissonances in each measure and how the choice to leave the thirds out of most chords impacts the way they sound. Ten minutes of analysis can yield a treasure-trove of musical ideas for students, including how to use iii and vi chords, how to achieve a sense of flow or stasis with the rhythmic choices and long non-chordal tones in accompaniment voices. Analysis exercises that include “why” as part of the analysis help students to practice social awareness, interpreting the intentions of the composer to convey some quality of emotion or sensation.

Figure 31.3. Notes and chords used in the opening of chorus of “Now Is the Cool of the Day,” written by Jean Ritchie, arranged by Peter and Jon Pickow, and adapted by James Erb (1971). Lawson Gould Publishers

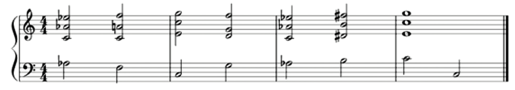

For another exercise, students can experiment with chord progressions with chordal instruments, notation programs, or online music tools like Chrome Music Lab Arpeggios4 to find a short chord progression (e.g., four bars of half notes) that they like as a homework exercise. Once they have arrived at a chord progression, they should write the letter names out and, if appropriate, the chord functions within a key signature (however, their chosen progressions may or may not fit common chord functions within a key). Next, students should notate the chord progression in root form and, even if it looks quite strange, explain why they like the chords in the order they chose. Figure 31.4 provides an example of a progression that a student might find.5

Figure 31.4. An experiment with a chord progression

Students should play the progressions for each other in small groups and group members provide feedback on the emotional and holistic qualities that they hear. These shares with discussion help students to practice social awareness and self-management, negotiating how to describe their interests and respond to others’ creative works in positive ways.

Students can learn more about part writing and the best ways to set individual voice parts by setting the progression to two treble clefs for SSAA or a grand staff and bringing the root down to the lowest voice (for example, the tenor voice could be voiced in the bass or treble clef) They will also hear differences in the expressive qualities between piano/program and the human voice. Based on what they hear, students may revise the progression (for example, the second and third chords in Figure 31.5) to provide a smoother bass voice. Further rearranging the chord tones to create smoother vocal lines may also reveals that the tessitura is uncomfortable for one or more voices (for example, the soprano in Figure 31.5), so the novice composer can be guided to rearrange pitches once more (Figure 31.6).

Figure 31.5. Voiced chord experiment with Chords 2 and 3 changed

Figure 31.6. Revised voicing with a remaining tenor challenge

Students should continue to experiment with voice placement to address difficulties that individual voices have (e.g., the tenor in Figure 31.6). They quickly discover voiceleading, range and tessitura, and evocative qualities that individual lines can sing as they experiment with voicing chord progressions and can also learn how passing and neighbor tones can help voices to transition between chords or can bring movement to the progression. They are likely to discover challenges such as the sound of parallel motion and difficult voice leadings in these exercises. These problems will help them to seek solutions that will, in turn, allow the teacher to provide instruction on common chord tones, common chord progressions, and cadences. Experimenting with voicing and re-voicing the vocal lines will help students to learn more about social awareness (how other’s will experience their music) and responsible (responsive, in this case) decision-making.

For a third exercise, the teacher can lead the choir in building chords. Starting with a pitch in the lowest voice, the teacher can have students stagger breath while holding the pitch, then add more voices to build a chord (open or closed) that includes sevenths, ninths, elevenths, and thirteenths tones. The notation should be with provided and the chord labeled for students. The teacher can then stop voices or bring the chord back to a simple root position, move the fifth to another voice and add a non-chord tone. The whole exercise should be recorded, and the file named. Students can listen to the chords they created and then discuss the expressive qualities of the chords they have sung and keep them in a chord library. Such exploration and discussion can help students to build their self-management skills because they will collect a library of musical chords, complete with the qualitative impact of each chord, to be able to express themselves through music.

Exercises Creating Layered Ostinatos.Layered ostinatos form the basis for circle singing, in which students form a circle and sing two to four layers of ostinatos while they take turns stepping into the center to improvise. Stephen Paparo (2016) provided guidance for chorus teachers to incorporate circle singing as a creative activity in choirs. A student leader should stand in the center of the circle and improvise a short melodic or rhythmic pattern, repeating the phrase and “giving it” to one part of the circle. A first layer of sound could also come from a song that the choir is already learning (bass line phrases often make good first ostinato layers because they outline or imply chord progressions). From there, the leader adds a second ostinato layer, inventing what they think will go along with and support the first ostinato, up to four ostinato layers. While the circle repeats their parts, individuals go into the center and have the opportunity to improvise freely, until they feel they’ve finished and trade places with a different student.

A teacher often finds that students, once circle singing is introduced, will practice creating and layering ostinatos outside as well as inside of choir class. To move beyond layering ostinatos, the teacher should record students and play the music back for them. Each layer should be extracted and notated, giving students a chance to practice dictation and analyze the music they have created. They are often surprised to find chord progressions they have created through the layered ostinatos. Circle singing builds relationship skills and responsible decision-making about how to act in the different roles.

Alternately, a program like Kandinsky in the Chrome Music Lab6 or an online DAW with loops will create an ostinato for students to improvise over. Short loops can be found or built, and then students sing over the repeated ostinatos. These explorations should be recorded and students journal about what they discovered about complementary rhythm, contrary motion, imitation, and the other musical gestures they work with. As before, this exercise can help students practice their relationship skills and responsible decision-making.

For another exercise, students can practice adding an ostinato to accompany this song (see “Tideo,” Figure 31.2). Students should determine or find the underlying chords for the song (a I chord, or a I-I-V-I progression in each measure). The teacher should direct students to experiment with different spoken and sung ostinatos with the intent to convey different emotional and holistic qualities. If students have difficulty thinking of different types of ostinatos, the teacher should play recordings of some folk or children’s songs set with ostinatos to great effect, like Fabian Obispo’s (2011) Mamayog Akun. The opening of this popular and challenging choral work sets the bouncy and light children’s song to strongly rhythmic, swinging ostinatos to produce a dance-like effect.7 Since different ostinatos will impact the effect of the song, students will practice their self-awareness in discussing what each type of ostinato adds to the expression of the song.

Exercises Practice Painting Emotional Qualities with Vowel Sounds.Exercises to practice composing with consideration for the sounds of words should begin with conversations about poetry and prose and reflections on the impact that different vowel sounds can have. Edgar Allen Poe’s poetry can be effective for inspiring discussions. Students can read, for example, the first verse of The Bells,8 with its playful “ih” and “in” and “ah” sounds that express joy, compared with the fourth verse that moves from “ah” to “oh” to “oo” to express foreboding and sorrow.

While the stars that oversprinkle, all the heavens, seem to twinkle With a crystalline delight; Keeping time, time, time, in a sort of Runic rhyme, To the tintinabulation that so musically wells From the bells, bells, bells, bells, Bells, bells, bells— From the jingling and the tinkling of the bells.

And from the fourth verse:

For every sound that floats from the rust within their throats Is a groan. And the people—ah, the people— They that dwell up in the steeple, All alone, And who tolling, tolling, tolling, In that muffled monotone, Feel a glory in so rolling On the human heart a stone—

Hip-hop artists and modern poets provide a wealth of powerful text to unpack and explore. Troy Osaki (2016), for example, speaking as Bruce Lee in his poem “Year of the Dragon” says: “I knew the reason why they sidestepped my fight scenes was to avoid staining their screens with slanted eyes.” The impact of this line lies not only in words like “fight scenes” and “staining . . . screens” and “slanted eyes” but in the long “a,” long “e,” and the “ah” that give a brilliance to the words. Students might compare the way Poe used those same vowels to convey happiness while Osaki uses them to convey anger, exploring together why these two emotions relate to the same vowel sounds.

For another exercise, students should work in groups to sing a simple chord progression on one vowel sound, then explore changing vowels in single voices or through the progression. Recording themselves, they will discover that closed “oh” and “oo” and “eh” vowels sound quieter than the more open vowels as well as the impact of different vowel sounds. We can all sometimes take for granted how different vowel sounds can produce an emotional impact, so analysis and discussion here will help bring social awareness to students by highlighting this important aspect of language. These exercises can also help students as novice composers to practice their self-management, learning to make decisions about how to express an emotion through the text of a poem they set to music.

Date added: 2025-04-23; views: 195;