The Legend of Atlantis: From Plato's Dialogues to Modern Science and Fiction

Atlantis is a hypothetical “lost continent” usually identified as having existed in the Atlantic Ocean. First mentioned by the Greek philosopher Plato (428/427-348/347 BCE) in two dialogues, Timaeus and Critias (both c. 360 BCE), Atlantis has subsequently been employed as a setting or concept by untold numbers of philosophers, pseudoscientists, explorers, novelists, and movie makers. In the process, the name has become a byword for any lost civilization.

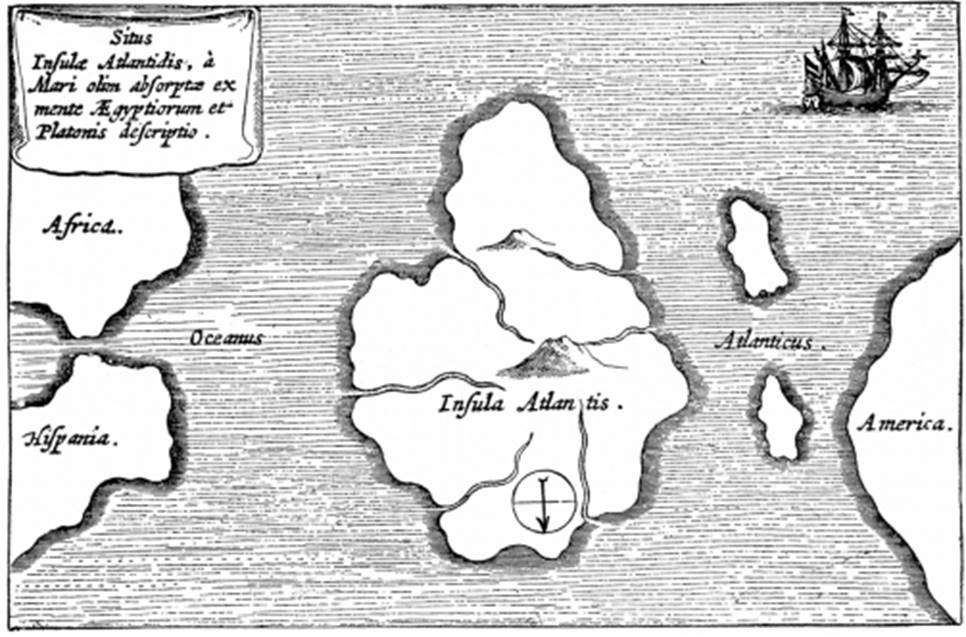

Famous engraving of Atlantis, as described by the German Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kirchner in his textbook Mundus Subterraneus, published in 1665 (Jupiterimages)

In Timaeus, Plato referred to Atlantis as a large island lying in the Atlantic Ocean beyond the Pillars of Hercules, a landmark traditionally identified by the two promontories overlooking the strait where the Atlantic and the Mediterranean Sea meet. Speaking through a character named Critias and attributing the information to the Athenian statesman Solon (c. 630-c. 560 BCE), Plato described Atlantis as the home of a great empire whose inhabitants had once conquered parts of Africa and Europe. However, the island had sunk into the sea some 9,000 years before.

In the second dialogue, Critias explains that the Atlanteans were the offspring of Poseidon (the Greek god of the sea) and a mortal woman. He describes Atlantis in idealized terms and recounts how its citizens established a great civilization and built a powerful navy thanks to their civic-mindedness. According to this account, the Atlanteans eventually fell away from their virtuous ways, leading Zeus, the king of the gods, to punish them. However, the dialogue ends at that point, with the remainder having been lost or perhaps never written.

It appears that Plato was telling a fanciful story in order to describe the characteristics of an ideal society. His account was interpreted in this manner by subsequent figures such as the English philosopher Francis Bacon (1561-1626), who set a Christian version of such a society on the imaginary Pacific Ocean island of Bensalem in his New Atlantis (1627). But the idea that Atlantis might have been real attracted a few adherents, including the German polymath Athanasius Kircher (1602-1680), who treated the story as true in his Mundus Subterraneus (1664).

The belief that there had been an actual Atlantis grew in popularity in the late nineteenth century. In an 1879 Popular Science Monthly article entitled “Atlantis Not a Myth,” would- be American archaeologist Edward H. Thompson wrote that the descendants of the Atlanteans had eventually made their way to Mesoamerica. But the greatest proponent of the lost continent was American politician Ignatius T. T. Donnelly (1831-1901), who produced a perennially popular work of pseudoscience in Atlantis: The Antediluvian World in 1882. Drawing upon the writings of Thompson and others, Donnelly argued that Atlantis had actually existed in the location Plato identified, that Poseidon had been one of its kings, that its inhabitants had spread civilization throughout the rest of the world, that its destruction had given rise to the legend of the biblical flood, and so on. In the wake of Donnelly’s unfettered speculations, others postulated the existence of lost continents in other parts of the world.

Imaginative writers also began to incorporate Atlantis into their works. Jules Verne portrayed it as a classical ruin on the bottom of the ocean in his Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (1870), while fellow French novelist Pierre Benoit (1886-1962) placed it in a vanished sea, long since transformed into the Sahara Desert, in Atlantida (1919). The British writer Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930) imagined a still-thriving underwater city in his 1929 novel The Maracot Deep. Since then, the motif of the lost continent has become commonplace in such fiction.

Researchers have speculated about real events that might have contributed details to the story of Atlantis. In the process, they have placed the elusive land in a wide range of locations, including not just the Atlantic Ocean but also the Mediterranean Sea, the coasts of Northern Europe, the Caribbean Sea, and so on. Perhaps the most plausible theory involves the explosive eruption of a volcano on the Aegean island of Santorini (Thera) in the second millennium BCE. It is believed that the cataclysm created an enormous tsunami that would have inundated the northern coast of Crete. Lying only 70 miles from Santorini, the larger island was the center of the Minoan civilization, which fell into decline over the following decades. Grove Koger

FURTHER READING:De Camp, L. Sprague. 1959. Lost Continents: The Atlantis Theme in History, Science, and Literature. New York: Dover.

Ellis, Richard. 1998. Imagining Atlantis. New York: Knopf.

Friedrich, Walter L. 2000. Fire in the Sea: The Santorini Volcano: Natural History and the Legend of Atlantis. Cambridge/New York: Cambridge University Press.

Ramage, Edwin S. and J. Rufus Fears eds. 1978. Atlantis, Fact or Fiction? Bloomington: Indiana University Press

Date added: 2025-10-14; views: 163;