The Great Pacific Garbage Patch: Scale, Impact, and the Race to Clean It Up

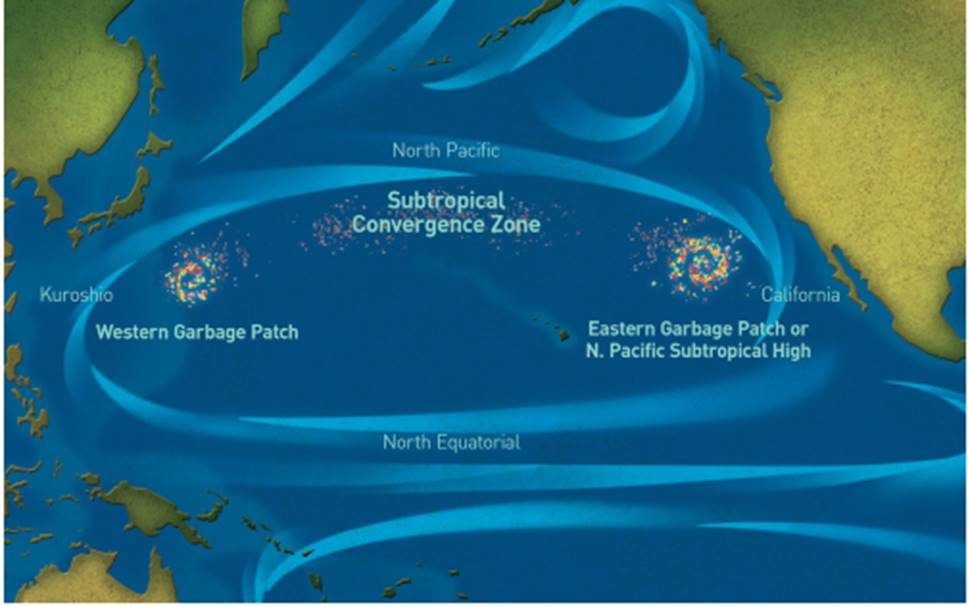

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch measures in as the world’s largest floating trash dump, although its exact size is impossible to measure because much of the debris can’t be seen in satellite photographs. The trash circulates with the currents, although two concentrations can be found—one in the east and one in the west. The eastern patch is found between Hawai‘i and California, and the western patch is found off the coast of Japan. Both patches rotate and move with the currents. The Subtropical Convergence Zone, found north of Hawai‘i where the warm waters of the South Pacific meet the cold waters of the Arctic Ocean, creates a strong current that carries the trash from one patch to the other. The entire area is surrounded by a clockwise current called a gyre that is caused by winds and the Earth’s rotation. This circulation, known as the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre, traps the trash in an area that is approximately 7.7 million m2 in size.

Cleanup efforts are complicated: the patch is so large that with today’s technology, it would be impossible to clean up the garbage in a reasonable amount of time. In fact, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) estimates it would take sixty- seven ships one year to clean up less than 1 percent of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. In addition, the oceans do not belong to anyone, and although the majority of the trash in the Pacific Garbage Patch comes from North America and Asia, no single country is willing to take on the job. Many individuals and organizations, however, are determined to find a solution to the growing problem in the Pacific Ocean, beginning with educating the public, as well as businesses, on the harmful effects of toxic disposable plastics.

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch circulates with the currents, creating two concentrations, one in the East and one in the West. The Eastern patch is found between Hawaii and California, and the Western patch is found off the coast of Japan (NOAA)

Walking on the beach anywhere on the western coast of North America, you may find debris the tide has brought to shore. You may well discover fishing nets, disposable lighters, a toothbrush, a tire, a comb, or bottle caps that have been lost from a ship’s container or thrown overboard on a fishing expedition; you might also see a water bottle, or even a toy or shoes that have been ravaged by ocean waves. There may be unidentifiable fragments with labels that may be recognizable and readable, or they may be written in a foreign language, perhaps Japanese or Indonesian. It is more than likely this debris floated to shore from the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. In 1997, while participating in a yacht race from Los Angeles to Honolulu, Captain Charles Moore came across a field of floating trash larger than he had ever seen. This debris field—filled with plastic bottles, caps, bags, and buoys—extended for miles. What Moore discovered was later named the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.

The Garbage Patch State. In 2013, several artists, in collaboration with the Italian Ministry of the Environment, as well as a number of Italian universities, decided to declare five garbage patches in the world’s oceans (two in the Atlantic, one in the Indian, and two in the Pacific) as a new federal state in order to raise awareness of the growing problem of ocean pollution. This imaginary Garbage Patch State covers an area of roughly 16,000,000 km2 (or roughly 6,000,000 m2) and has a listed population of 37,000 tons of plastic. Since the creation of the “state,” the affiliated artists stage exhibits throughout Europe to highlight their environmental cause. An official website dedicated to the Garbage Patch State allows individuals to send greeting cards from the imaginary state (http:// www.garbagepatchstate.org). Rainer F. Buschmann

How Garbage Pathes Form.Since Moore’s discovery, sailors and scientists alike continue to see floating islands on the ocean’s surface, some solid, others with pieces of trash and debris floating closely together yet independently, all moving with the wind and driven by the ocean’s currents. Plastic and debris fields are far-reaching and span from the Western Garbage Patch near Japan to the Eastern Garbage Patch between Hawai‘i and California. Plastics are the most common pollutants in ocean waters. Plastic and other debris are pushed by the winds, tides, and ocean currents in a circular motion, forming ocean “gyres,” or circular ocean surface currents.

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch may be the most infamous and the largest of the world’s floating trash dumps; however, it is not the only one on our planet. There are as many as five in the Earth’s oceans. Trash litters the Bay of Bengal, the Mediterranean Sea, Indonesia’s coast, and other coastal regions, where it gets trapped in bays and gulfs.

Environmental Impact of Marine Debris.Since Captain Moore’s discovery in 1997, the Great Pacific Garbage Patch has gained the attention of environmentalists and scientists from around the globe, mainly because of its immense size, and also because of the risk it poses to fish, turtles, and birds that mistakenly believe the debris is food. Turtles often mistake plastic bags for jellyfish. Albatrosses mistakenly feed their young plastic resin. Seals and other marine mammals are found tangled in nets that have been either thrown away or lost by fishermen and ocean cargo ships and other vessels. The sun breaks down debris and plastic trash, which in turn blocks sunlight from reaching plankton and algae, an important source of food for marine life.

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch’s sheer vastness is not readily seen from a ship or from the air. The debris, including tiny bits and larger pieces of plastic, and such items as fishing gear, shoes, or even tires, may be floating within the depths of the ocean or resting on the ocean floor. This makes the volume of debris impossible to measure, or for anyone to gather the trash within a net of any size in an attempt to effectively clean the sea. Most of the trash and debris within the Great Pacific Garbage Patch come from land areas. A lesser amount comes from offshore sea vessels and oil rigs.

Researching Solutions.Individuals and international organizations around the globe are dedicated to cleaning the world’s oceans. One such organization is the Algalita Marine Research Foundation, formed by Charles Moore, whose mission is to study the effects of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch on marine life and to assist in the effort to clean up the sea. Moore’s organization has been trawling the patch and studying the collected debris, which is then tagged and stored.

Due to the complexity and sheer amount of debris and garbage that floats within the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, which is located far from either the Asian or North American coastlines, no nation is willing to commit to funding the cleanup of the Pacific patch. Although scientific expeditions continue to travel through it to raise awareness, cleaning up the patch is difficult. In a 2014 expedition, Moore’s foundation used aerial drones and discovered islands formed by debris measuring nearly 50 feet in length. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Marine Debris Program has been actively studying the patch and seeking a solution to cleaning the ocean. It estimates nearly seventy ships would need more than a year to clean up about 1 percent of an area in the Northern Pacific Ocean.

Nevertheless, cleaning efforts are underway. The most successful of these projects, the Ocean Cleanup Project, has experimented with suspending a large catchment between two vessels. Trawling the Pacific Ocean at a languid pace of less than two miles per hour, the enormous device collects plastics on the surface and drives them toward a large, suspended sack that is periodically emptied onto one of the vessels. The plastic is separated into different categories and placed in appropriate containers. While its first two systems gradually increased the catchment area, the latest iteration—System 03, tested in 2023 and deployed in 2024—has a catchment area of nearly 2,500 meters. Modern equipment guides the vessels to prominent hotspots of concentrated plastic that promise large catches.

Initial returns of these vessels are promising, and supporters of the Ocean Cleanup Project, with as many as ten systems deployed, are now predicting that by 2040, the Great Pacific Garbage Patch will have been reduced by 90 percent. However, the Ocean Cleanup Project also has its critics. Scientists have recently discovered the development of sea life in the garbage patch. While the organisms consist primarily of jellyfish and snails, the emergent ecosystem could be destroyed by the extensive sweeps of the ocean’s surface. Joann F. Price

FURTHER READING:Kostigen, Thomas M. You Are Here. New York: HarperOne, 2008.

Pyrek, Cathy. 2016. “Plastic Paradise: The Great Pacific Garbage Patch.” The Contemporary Pacific 28 (1): 268-70.

Sacks, Danielle. 2010. “The Great Pacific Garbage Patch.” Fast Company 144: 28.

Date added: 2025-10-14; views: 204;