Maritime Empires: History and Global Impact

Maritime empires are political systems composed of scattered dependencies ruled by centralized national authorities and maintained by sea. The largest and most powerful maritime empires began to emerge as colonial systems during the Age of Exploration (late fifteenth through eighteenth centuries) and reached their greatest extent during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In many cases, innovations in shipbuilding, navigation, and commerce contributed to their growth.

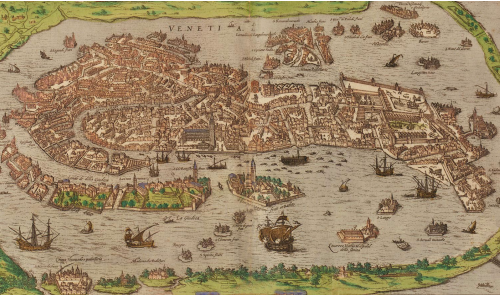

A 1493 view of Venice from the Nuremberg Chronicle, an illustrated history of the earth from creation through the fifteenth century. The Republic of Venice’s favorable location astride trade routes linking Europe to the Red Sea and beyond helped Venice to become one of the most prosperous cities in Europe in the fifteenth century (Jay I. Kislak Collection, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress).

Maritime powers of various types have played key roles in Europe and Asia throughout history. The city-states of ancient Greece, for instance, spread their culture across the Mediterranean beginning in the mid-eighth century BCE, but they seldom functioned as a single political entity. The Hanseatic League traded actively throughout the North and Baltic Seas from the mid-twelfth through the mid-seventeenth centuries CE, but as its name suggests, it was a league or confederation.

The first European power that could be called a maritime empire was Venice, whose 1082 treaty with the Byzantine Empire had already given it valuable access to spices and other trade goods from South and East Asia. Over the course of the following centuries, the Italian city extended its territorial acquisitions down the eastern coast of the Adriatic Sea and into the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean Seas. At one point the city’s navy consisted of more than 3,000 ships, including swift galleys propelled by multiple banks of rowers, and its shipyard was so efficient that its workers could build a ship in a day’s time.

Venice fell into decline when Portuguese explorers rounded the southern tip of Africa and opened maritime trade routes to Asia in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. Portugal’s coasts are on the Atlantic Ocean, and the country’s shipbuilders had developed vessels that could be maneuvered easily on the open seas. Called caravels, they were fast ships with two to four masts and lateen (triangular) sails. Carracks—larger three- and four-masted ships square-rigged on their foremasts and mainmasts and lateen-rigged further aft—were subsequently adopted for long-distance trade. Portuguese mariners also had the advantage of using astrolabes, instruments that made it possible to determine their latitude at sea.

Portugal went on to amass history’s first global empire, which by the early nineteenth century included islands in the North Atlantic Ocean, territories in South America and Africa, scattered outposts on the coasts of India and China, and an island in the East Indies. Relying on ships similar to Portugal’s, Spain also established a far-flung empire that included large territories in the Americas, several more on the western coasts of Africa, and a number of island groups in the Pacific Ocean. The Netherlands, Britain, and France began to create maritime empires of their own in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, and were followed by the United States, Belgium, Italy, and Japan in the nineteenth century. In many cases, the process initially involved the establishment of joint-stock companies that allowed individuals to share the risks of long-distance trade by sea, as well as the potential profits.

During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Portugal, Spain, and Germany lost sea power and many, if not all, of their possessions to nationalist movements and conflicts with competing nations. But over the same period, Britain came to control not only the largest maritime empire in history but also the largest empire of any kind. Its success was due to numerous factors, including access to a generous supply of timber and—as wood construction and wind power gave way to steel construction and steam power—iron ore and coal. Britain also took control of the Suez Canal, a link that shortened the sea route to its prized possession of India by several thousand miles. By the time it reached its greatest extent, in the early twentieth century, the British Empire encompassed nearly a quarter of the Earth’s land.

In 1939 Britain’s merchant marine accounted for one-third of the world’s tonnage, and its navy was the largest in the world. However, the Second World War (1939-45) left the nation weakened, and over the course of the following decades, Britain gave up virtually all of its possessions. The remaining maritime empires shed most of their possessions as well, although several found themselves involved in lengthy conflicts before doing so.

FURTHER READING: Howarth, David Armine. 2003. British Sea Power: How Britain Became Sovereign of the Seas. New York: Carroll & Graf.

Madden, Thomas F. 2012. Venice: A New History. New York: Viking.

Reynolds, Clark G. 1974. Command of the Sea: The History and Strategy of Maritime Empires. New York: Morrow.

Scammell, Geoffrey Vaughn. 1981. The World Encompassed: The First European Maritime Empires, c. 800-1650. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 2;