English-Only Policy at the State Level

Legal requirements promulgating the use of English are by no means new in the United States. Historically, literacy in the English language has been used in various states to discriminate against nonwhites and foreign-born Americans. In the 1850s, several New England states enacted laws requiring voters to prove English literacy. These laws were intended to disenfranchise the burgeoning population of illiterate Irish-American immigrants who had escaped the devastation of the potato famine.

As more and more immigrants from southern, central, and eastern Europe arrived in the late nineteenth century, more states passed laws intended to restrict the use of foreign languages. In 1890, the state of Wisconsin passed a compulsory education law requiring that instruction be given in the English language. At that time, three-quarters of Wisconsin's population was foreign-born or native-born of foreign-born parents.

The compulsory education law aroused a storm of political opposition throughout the state. Supporters of the law, including the governor, were defeated at the polls, and the law was soon repealed. In 1915, New York enacted an English-language literacy law aimed at restricting immigrant voting. Not until 1966 was this law, now challenged by Spanish-speaking Puerto Ricans, declared unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court.

The English-only controversy has also affected foreign-language instruction in American schools. During and shortly after World War I, a nationwide movement against the use and teaching of German in American schools developed. In 1917 and 1918 alone, twenty-five states passed laws removing German from school curricula. The anti-German movement was by no means limited to education. Americans of German ancestry experienced unprecedented discrimination. In response, many legally changed their Germanic surnames. German words were hastily dropped from the language: sauerkraut, was known as "liberty cabbage," while frankfurters became hot dogs. Some states enacted laws restricting the use of foreign languages. Oregon enacted a law prohibiting the publication of newspapers and periodicals in languages other than English. These too were overturned by Federal court.

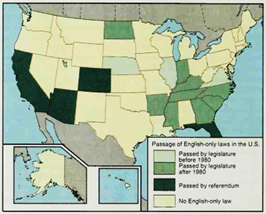

Current Efforts to Legislate English as an Official Language. During the 1980s, the issue of English as the official language of the United States became an important political controversy throughout the nation. In 1980, English as an official language had been legislated in only three states, but by 1988 all but three had at least considered such legislation. By mid-1990, the legislatures of thirteen states had passed laws specifying English as an official language (Figure 4-14).

Figure 4—14 English as an Official Language. The number of states that have passed laws specifying English as an official language has been steadily growing since the 1980s

The issues underlying conflict over the designation of English as an official language were articulated clearly in bitter election campaigns in California during the 1980s. The campaign to make English the official language of California began in 1983, when the voters of San Francisco responded to a ballot initiative about the printing of ballots and voting materials in city elections in English only. This agenda was known as Proposition "O." Previously, ballots had been printed in Spanish and Chinese, as well as in English. About 15 percent of San Francisco's voting age population were not literate in English.

Proponents of Proposition "O" advanced several arguments in favor of the new law. Universal knowledge of English was defended on the grounds that it encouraged national unity and the mobilization of a fully informed electorate, hence promoting citizenship. Others felt that printing ballots in other languages discouraged the learning of English and thwarted economic advancement. They argued further that it promoted corruption in state politics.

The San Francisco Chronicle supported the proposal. Its editors argued that non-American born citizens should be able to comprehend a ballot printed in English. If they cannot, they go to the polls unable to even understand what candidates have been saying, a poor basis on which to exercise political judgment. ... In close elections, a candidate might prevail because he has assembled the largest number of poorly-informed and incompetent voters. Proposition "O" was enacted in November 1983, with two-thirds of the vote.

In general, those states whose legislatures have adopted English as an official language are home to relatively few foreign-born residents whose native language is not English. On average, only 3 percent of these states' residents do not speak English at home, as compared with 10 percent in states whose legislatures have not passed English-only laws. English-only proposals have been defeated or tabled in every state with significant non-English-speaking minority populations.

Following legislative refusal to pass English-only laws, voters in four states with high proportions of non-English-speaking residents—Florida. Colorado, Arizona, and California—enacted amendments to their state's constitutions through the initiative process, by which the people vote directly on legislation.

The California initiative, adopted in 1986, was typical of the political debate concerning popular support for official English. Although the California legislature had rejected English-only proposals, polls of the public taken prior to the election showed broad support for the initiative. Support for Proposition 63 among Asians and Hispanics was only marginally smaller than that among native-born whites and African- Americans, and it was relatively uniform across income levels. Democrats, who are more dependent on votes from ethnic minorities and immigrants, were somewhat less likely to support the proposal than Republicans.

Proposition 63 was enacted with well over 60 percent voter support. After the election, observers noted a strong correlation between support for the issue and support for national identity. To many English-speaking Americans, use of the English language is seen as an important component of national identity. Those who accepted this premise were far more likely than those who did not to support legislation concerning English as an official language.

Date added: 2023-03-03; views: 654;