Brazil. Cities Old and New. Colonial cities. A modern metropolis. A most contemporary capital

From the modern skyscrapers of Sao Paulo to the cobbled streets of Ouro Preto, each of Brazil's cities reveals another fascinating chapter of the country's history. Traveling along the nation's 4,600-mile (7,400-kilometer) Atlantic coast is a journey back to Brazil's colonial past—and a glimpse of its vision for the future.

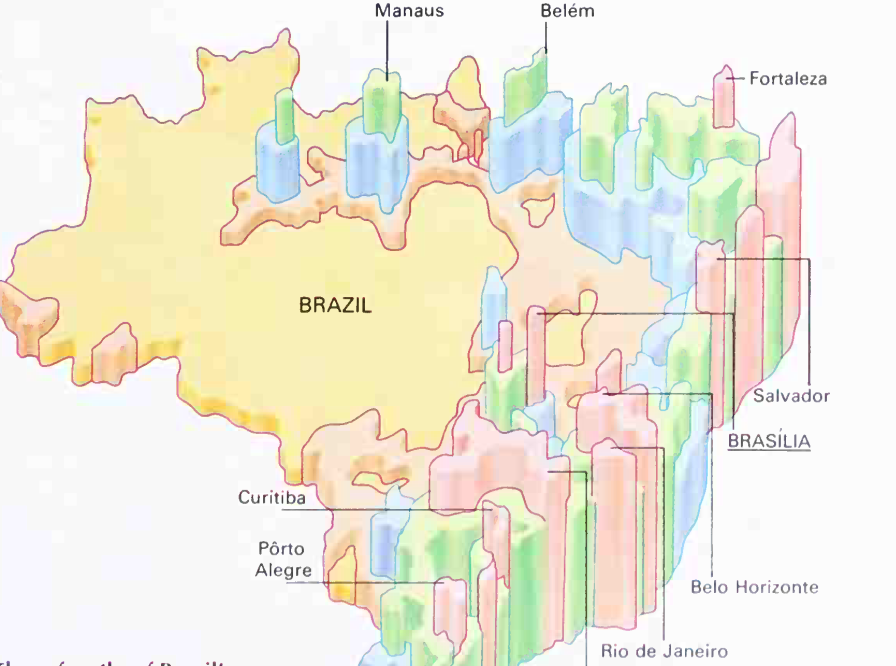

Three-fourths of Brazil's people live in urban areas, mainly within 100 miles of the Atlantic coast and in the southeast. Some of Brazil’s first cities were built along the northeast coast during the early days of Portuguese and Dutch exploration.

Colonial cities. Few cities capture Brazil's early colonial days as vividly as Recife and Olinda. Situated on the northeast coast, Recife and Olinda were occupied by Dutch colonists during their attempt to stake a claim to Brazilian territory in the 1600's. Recife is often called The Venice of Brazil because it is built on three rivers, and many bridges connect its islands and peninsulas.

Residents of a shantytown built over the river in Salvador, Bahia, cross a rickety bridge to their homo. Founded in 1549, and now the third largest city in Brazil, Salvador served as the capital of the Portuguese colony of Brazil between 1549 and 1763

The influence of both the Dutch—and the Portuguese who drove them out—can be seen in Recife's historic downtown area, where many lavishly decorated churches from the 1600's and 1700's still stand. The Gold Chapel of the monastery of Saint Anthony, one of the most important examples of religious art in Brazil, has a baroque design covered in gold leaf.

In Olinda, now a .suburb of Recife, narrow, winding streets twist up and down the hills overlooking the ocean. Many of the houses have the original latticed balconies, heavy doors, and pink stucco walls typical of the colonial period.

Farther south and hidden deep in the Brazilian Highlands is Ouro Preto, the center of the gold and diamond trading in the 1700's. Ouro Preto means Black Gold, and so much gold came from the hills around Ouro Preto that the area was called minas gerais (general mines), which became the name for the modern state of Minas Gerais.

When the gold ran out, many people left Ouro Preto, but the artistry of the brilliant mulatto sculptor of the period, Antonio Francisco Lisboa da Costa (known as Aleijadinho), remains. Aleijadinho carved many human figures and church decorations out of soapstone.

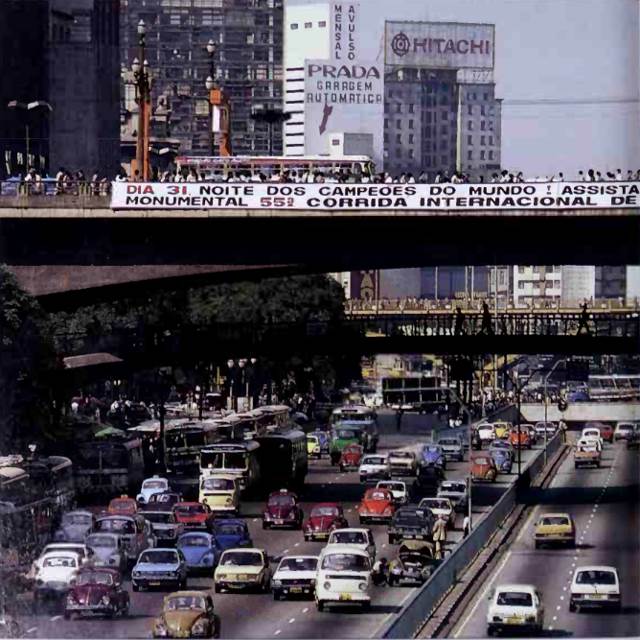

A modern metropolis. Unlike Brazil's colonial cities with their old buildings and winding streets, Sao Paulo is a thoroughly modern city. Although it was founded in 1554 as an Indian mission, Sao Paulo has a long tradition of tearing down the old and putting up the new. Most of Sao Paulo's buildings are less than 100 years old, and few of the old churches remain.

Today, Sao Paulo is the largest city in Brazil and its leading commercial and industrial center. The wide avenues of the downtown area are lined with imaginatively designed skyscrapers and high-rise apartment blocks. Large parks and gardens provide a welcome sense of spaciousness in this crowded city.

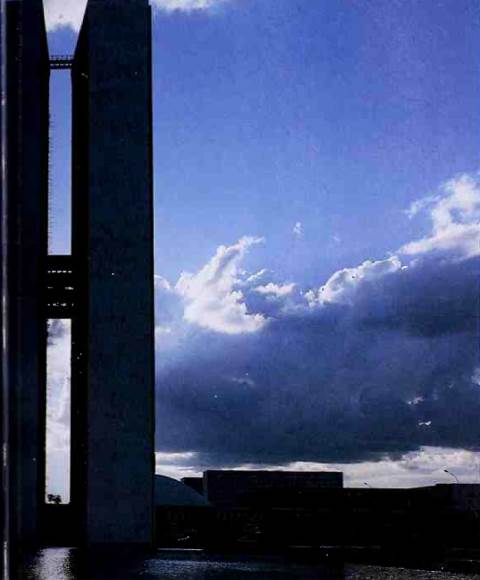

Twin towers in the capital city of Brasilia, above, house congressional offices, while the Chamber of Deputies meets in the bowl-shaped structure to the left. Viewed from the air, Brasília is laid out in a pattern that resembles a drawn bow and arrow

A most contemporary capital. Sao Paulo is a sprawling city, growing faster every day with little direction from the government. In contrast, Brasilia, the capital of Brazil, is one of the world's leading examples of large-scale city planning. Built in the east-central Brazilian wilderness in the late 1950's, Brasilia is noted for its orderly development and impressive modern architecture.

The city was built as a link between the expanding south and the economically poor Northeast and as a launching point for settlement of the vast interior of the country. The government hoped that Brasilia would attract people from the crowded coastal cities to the underpopulated interior. Today, Brasilia is a hub of highways extending north to Belem in the Amazon Region and west to Peru.

Automobile traffic crowds an expressway in downtown Sao Paulo, left. The largest city in South America, Sao Paulo also has the second largest metropolitan area in the world. The city and sur- rounding area account tor about halt of Brazil's industrial output.

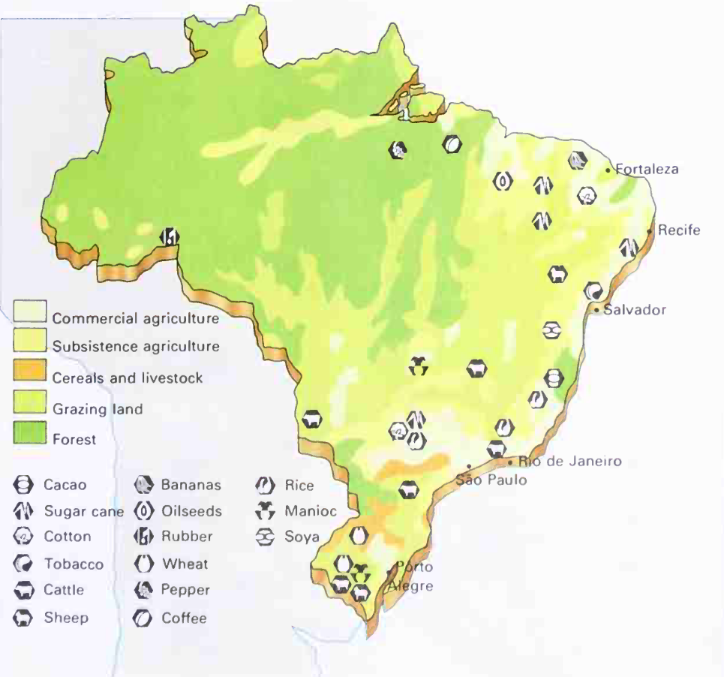

Brazil. Agriculture. "Boom and bust" cycles. Crops and farming regions. Feeding the people

Brazil has a vast amount of fertile farmland, and crops grown for export have been the main basis of the nation's economy since the earliest colonial days. Although factory production and service industries now contribute more to the GNP (gross national product), Brazil is still a world leader in crop and livestock production. Only the United States exports more farm products.

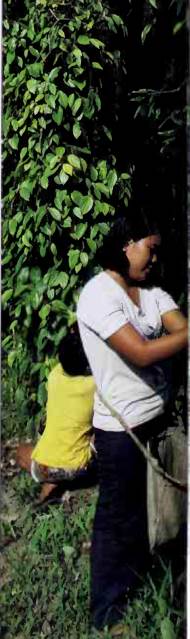

Women gather the berries of the pepper plant, which will be dried and sold as peppercorns or ground black pepper. Most rural people work on the large plantations or ranches of corporations or wealthy and owners, but some work their own small farms with traditional tools.

"Boom and bust" cycles. Beginning with the cultivation of sugar cane in the 1500's, Brazil's landowners have concentrated their efforts on growing a single crop for export in a series of "boom and bust" agricultural cycles. In each case, Brazilian farmers specialized in growing the crop that was in greatest demand on the world market at the time.

Brazil earned enormous profits during the "boom" of the crop demand, when prices were highest. But competition from other countries—or a decrease in demand—eventually brought prices tumbling down, resulting in a "bust."

Most of Brazil's chief farming and grazing areas are centered in the south and east of the country. Agriculture accounts for about 15 per cent of Brazil's economic output and employs about 30 per cent of the nation's workers.

In the late 1800's, for example, Brazil developed the Amazon Region's vast natural rubber resources in response to the worldwide demand for rubber products. But during the early 1900's, new rubber supplies from Asia reduced the great demand for Brazilian rubber. As rubber production decreased, coffee production increased. Then, in the 1920's, the price of coffee fell sharply, and thousands of plantation workers lost their jobs.

Crops and farming regions. During the 1980's, the Brazilian government encouraged farmers to grow a greater variety of crops. In addition to coffee, Brazil now leads all nations in growing bananas, cassava (a tropical plant with starchy roots), oranges, papayas, and sugar cane. It is also one of the world's top producers of cacao beans, cashew nuts, corn, cotton, lemons, pineapples, rice, soybeans, and tobacco.

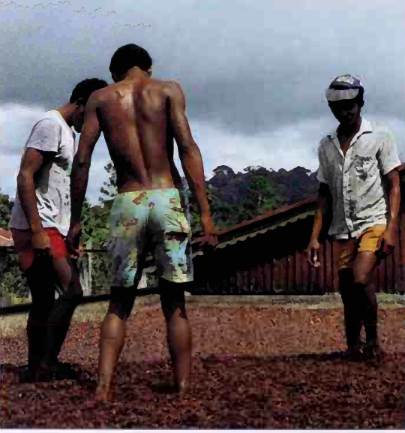

Brazilian laborers arrange cacao beans in an even layer to dry in the sun. Cacao beans, taken from the seed pods of an evergreen tree, are used in the production of chocolate and cocoa. Brazil is one of the world's largest suppliers of cacao.

Southern Brazil contains most of the nation's productive farmland. For many years, the state of Sao Paulo ranked as Brazil's chief coffee-growing region, but the northern part of Parana now supplies about half the coffee crop.

In addition to crops, Brazil is a leading producer of livestock, and cattle production has been a major source of wealth since World War (1914-1918). Brazil ranks as one of the leading hog producers in the world today, and farmers also raise chickens, horses, and sheep.

In 1975, the traditional plantation crop of sugar cane became a source of fuel as well as of refined sugar. General Ernesto Geisel, who was president at the time, began a program to reduce Brazil's dependence on oil imports by substituting alcohol for gasoline made from oil. Today, nearly half of all Brazilian cars use alcohol distilled from sugar cane instead of gasoline.

A young boy watches over a sugar cane field

Feeding the people. In addition to large cash crops of cacao beans, coffee, oranges, soybeans, sugar cane, and tobacco, Brazilian farmers grow such staples as cassava, beans, corn, rice, and potatoes for domestic use. However, the fast-growing population is outstripping the country's food supply. As a result, Brazil has had to import some food, particularly wheat, to feed its people.

Despite this situation, government policies—designed to reduce Brazil's huge foreign debt—encourage newly cultivated land to be used for growing high-profit cash crops. As a result, the increase in the percentage of land devoted to export crops was far greater than the increase in land used for domestic production during the 1980's.

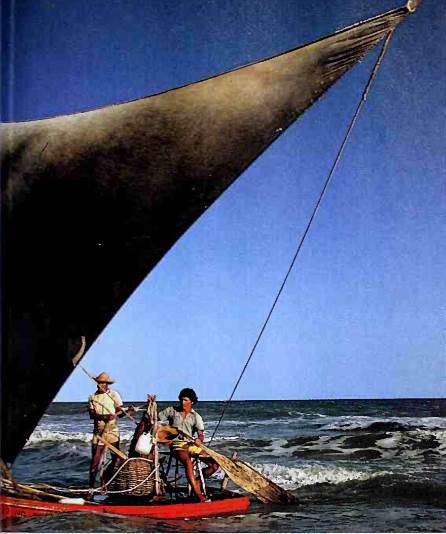

Fishing crews in a jangada sailing raft, right, the traditional coastal fishing boat of northeast Brazil, brave the waters of the Atlantic. Despite excellent fishing grounds off the South Atlantic coast, large-scale commercial fishing in Brazil is undeveloped.

Brazil. Industry. Plants and factories. Service industries. Brazil's Northeast.

Brazil’s natural resources, including its fertile farmland and rich mineral deposits, have been the backbone of the nation's economy through much of its history. However, rapid industrial growth during the mid-1900's has helped Brazil become one of the world's leading manufacturing nations.

Except for textile mills, industrial development did not actually begin to blossom until Brazil became an independent nation in 1889. Before that time, Portuguese rulers had discouraged industrial development in the colony because they wanted the Brazilians to buy Portugal's manufactured goods.

Independent prospectors mine for gold, right, at Serra Pelada (Naked Mountain) in the Amazonian state of Para. During the dry season, which lasts from June to November, up to 60,000 miners come here to seek their fortunes.

Once Brazil gained independence, industry enjoyed considerable growth under the leadership of Pedro II, who ruled for almost 50 years. Textile mills, breweries, chemical plants, and glass and ceramic factories were built, especially in Sao Paulo.

Between 1948 and 1976, the nation's greatest period of industrial growth, industrial production increased at an average rate of 9 per cent a year. In 1977, for the first time, manufactured products accounted for more than 50 per cent of the value of Brazil's exports. Manufacturing now accounts for about 27 per cent of Brazil's GNP (gross national product) and employs about 17 per cent of the nation's workers.

However, such tremendous growth has had its price. To speed industrial development, the Brazilian government borrowed heavily from foreign countries during the 1970's. Later, Brazil's huge foreign debt helped trigger hyperinflation. In 1990, President Fernando Collor de Mello froze larger bank deposits in an effort to slow down the inflation rate. He also began to sell some of the state-owned businesses to private corporations.

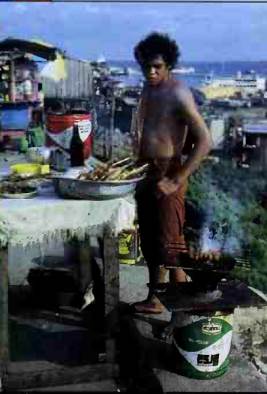

A street vendor in Manaus, below, sells churrasco, a selection of charcoal-barbecued meats. Despite Brazil's industrial development, millions of its people are extremely poor and work in low-paying jobs, if they can find work at all.

Plants and factories. Today, Brazil ranks among the world's major automobile producers, manufacturing more than 900,000 cars a year. Many international carmakers operate plants in Brazil. Latin America's largest iron and steel plant is located at Volta Redonda, near Rio de Janeiro. Brazil is also a major textile producer.

Other important industries include the manufacture of airplanes, cement, chemicals, electrical equipment, food products, machinery, pharmaceuticals, paper, and transportation equipment. Most manufacturing activity remains centered in the state of Sao Paulo.

Technicians at an Embraer aircraft plant install the nose cone of an airplane.

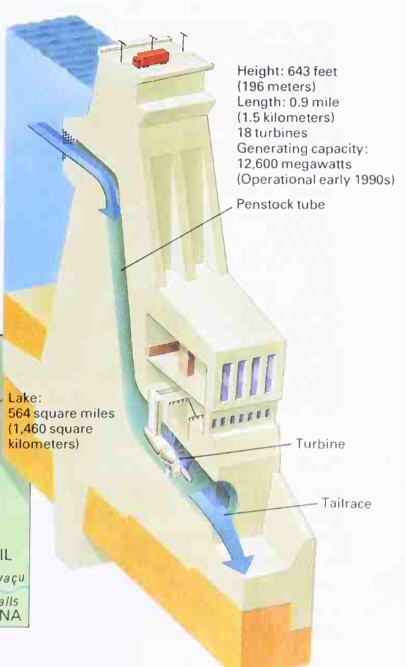

Brazil's natural resources provide the power and raw materials for its industry. For example, the vast iron ore deposits in Minas Gerais have helped the steel industry expand; large hydroelectric power stations operate on the Parana, Sao Francisco, and Tocantins rivers; and hydroelectric power stations provide almost all of the nation's electricity.

Service industries. From 1940 to 1980, the percentage of Brazil's workers employed in service industries increased from 20 to 40 per cent. Today, service industries account for about 55 per cent of Brazil's economic output—more than industry and agriculture combined.

Many business services, such as banking, communications, insurance, and transportation, have developed to meet the needs of Brazil's industries. Another important area of growth has been among government agencies responsible for providing medical care and education.

The Itaipu Dam power plant on the Parana River, a joint $20-billion project between Brazil and Paraguay, was designed to supply one-fifth of Brazil's energy needs.

Brazil's Northeast.From Fortaleza in the north to Salvador in the south, Brazil has some of the most glorious, palm tree-fringed, unspoiled beaches in the world. A tropical climate, fanned by Atlantic breezes, attracts tourists by the thousands. And the fertile red clay soil of the coastal plains that lie inland from the white beaches is ideal for growing sugar cane, cacao, and tobacco.

The Cathedral Basilica, built in the 1600's, dominates the plaza of Terreiro de Jesus in Salvador, the capital of Bahia. During the 1600's, the sugar cane industry flourished in the Northeast. Many splendid churches and buildings still stand as a reminder of the region's former wealth.

In the plateaus and lowlands of the interior, beyond the sun-drenched sands and sugar cane fields, lies the dry, harsh face of tropical Brazil—the sertao. As British journalist James Cameron wrote, it is "known as the land of miseria morte: the sorrows of death." Together, the coastal plains and the sertao form Brazil's Northeast, home to more than 35 million people and Brazil's poorest region.

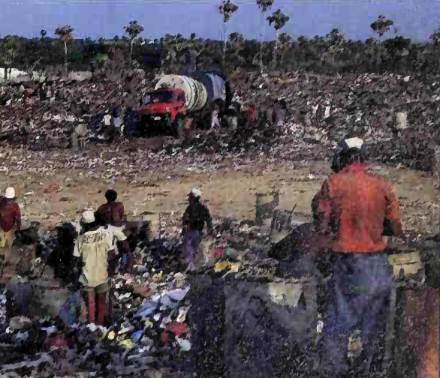

On the outskirts of Fortaleza, Nordestinos (inhabitants of the Northeast) made homeless by one of the region's periodic droughts search for scraps in a city dump, below. The poverty of the Northeast stands in stark contrast to the wealthy, more developed southern region of Brazil.

A land without mercy. The sertao is a desert that consists mainly of vast stretches of scrub forest known as caatingas, where droughts occur every 12-15 years and may last up to two years. During these times, the land becomes so dry that deep cracks form in the parched ground. Hot winds add to the dismal picture, as the lifeless soil swirls around the small, pitted hills that dot the landscape.

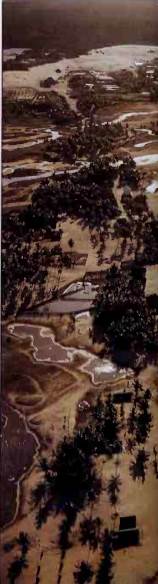

Coconut palms shade a wide, sandy beach near Fortaleza on Brazil's northeast coast, bottom center. Here, annual temperatures average a pleasant 80° F. (27° C), but the dry interior sertao suffers frequent droughts.

Stunted, thorny trees and cactus plants stand starkly against the sky, while others twist along the ground like huge snakes. Dwarf desert vegetation grows close to the ground to avoid the burning rays of the daytime sun. At night, the temperature drops sharply, and a chill sets in under the brilliant canopy of stars.

Eventually, the rains come, bringing relief to the drought-stricken land. Streams of water rush over the gaping cracks in the land and are swiftly absorbed. Thirsty vegetation springs to life, and the scent of blossoming flowers fills the air. Sometimes more damage is done by torrential rains than by droughts.

People of the backlands. In this harsh yet strangely beautiful land, millions of Nordestinos (northeasterners) struggle to make a living. Brazilians call those who try to work this often-shriveled, useless land Flagelados (The Beaten Ones) — because their life is difficult, and their rewards are few. Even in the best of seasons, the Flagelados can hope for little beyond tending scrawny cattle and growing what crops they can in the region's poor soil, or begging.

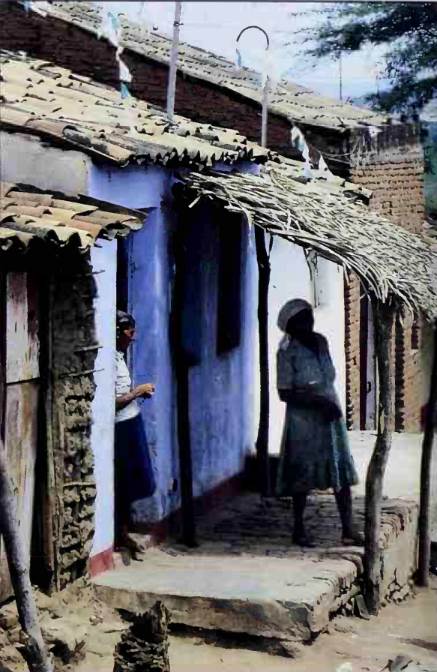

Small adobe houses with clay-tiled roofs line the main street of a village in the Northeast state of Ceara. Opportunities are few for the people of the Northeast, and many leave their villages to seek work in the cities of southern Brazil.

Many Nordestinos will die before they reach their 50th birthday, and many cannot read or write, but they are fiercely loyal to the backlands. Even when they are forced to migrate to the cities to make a living, many return to the sertao when they have saved enough money to live on.

It was the sertao and the human misery that inspired one of Brazil's most famous books —Os Sertoes (The Backlands), written in 1902 by Euclides da Cunha. The book described a peasant rebellion that took place there in the 1890's.

Date added: 2023-03-21; views: 816;