Scientists Use Controlled Experiments

When scientists are studying a phenomenon, they often perform experiments in a laboratory where extraneous variables can be eliminated. A variable is a factor that can cause an observable change during the progress of an experiment. Experiments are considered more rigorous when they include a control group. A control group goes through all the steps of an experiment but lacks the factor or is not exposed to the factor being tested.

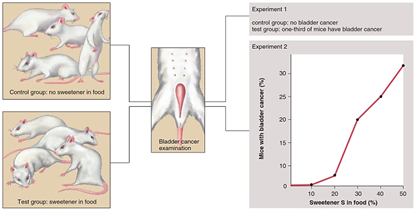

Designing the Experiment. Suppose, for example, physiologists want to determine if sweetener S is a safe food additive. On the basis of available information, they formulate a hypothesis that sweetener S is a safe food additive even when it composes up to 50% of dietary intake. Next, they design the experiment described in Figure 1.7 to test the hypothesis.

Figure 1.7 Design of a controlled experiment. Genetically similar mice are randomly divided into a control group and one or more test groups that contain 100 mice each. All groups are exposed to the same conditions, such as cage setup, temperature, and water supply. The control group is not subjected to sweetener S in the food. At the end of the experiment, all mice are examined for bladder cancer. The results of experiment 1 and experiment 2 are shown on the far right

Test group: 50% of diet is sweetener S

Control group: diet contains no sweetener S

The researchers first place a certain number of randomly chosen inbred (genetically identical) mice into the various groups—say, 100 mice per group. If any of the mice are different from the others, it is hoped random selection has distributed them evenly among the groups. The researchers also make sure that all conditions, such as availability of water, cage setup, and temperature of the surroundings, are the same for both groups. The food for each group is exactly the same except for the amount of sweetener S.

At the end of Experiment 1 in Figure 1.7, both groups of mice are to be examined for bladder cancer. Let's suppose that one-third of the mice in the test group are found to have bladder cancer, while none in the control group have bladder cancer. The results of this experiment do not support the hypothesis that sweetener S is a safe food additive when it composes up to 50% of dietary intake.

Continuing the Experiment. Science is ongoing, and one experiment frequently leads to another. Physiologists might now wish to hypothesize that sweetener S is safe if the diet contains a limited amount of sweetener S. They feed sweetener S to groups of mice at ever-greater concentrations:

Group 1: diet contains no sweetener S (the control)

Group 2: 5% of diet is sweetener S

Group 3: 10% of diet is sweetener S

Group 11: 50% of diet is sweetener S

Usually, data obtained from experiments such as this are presented in the form of a table or a graph (see Experiment 2, Fig. 1.7). Researchers might run a statistical test to determine if the difference in the number of cases of bladder cancer among the various groups is significant. After all, if a significant number of mice in the control group develop cancer, the results are invalid. Scientists prefer mathematical data because such information lends itself to objectivity.

On the basis of the data, the experimenters try to develop a recommendation concerning the safety of sweetener S in the food of humans. They might caution, for example, that the intake of sweetener S beyond 10% of the diet is associated with too great a risk of bladder cancer.

We have seen that scientists often use the scientific method to study the natural world. A particular observation backed up by data collected previously helps them formulate a hypothesis that is then tested. Testing consists of carrying out an experiment or simply making further observations. Particularly, if the experiment is performed in the laboratory, it should contain a control sample.

The control sample goes through all the steps of the experiment but lacks the factor or is not exposed to the factor being tested. In this way scientists know that their results are not due to a chance event that has nothing to do with the variable being tested. Finally, scientists come to a conclusion that either supports or rejects the hypothesis. Scientists report their findings in journals that are read by other scientists who also make similar observations or carry on the same experiment. If experiments and observations are not repeatable, the hypothesis is subject to rejection. If use of the scientific method results in conclusions that repeatedly support the same hypothesis, a theory may result.

As time goes by, it is possible that a hypothesis/theory previously accepted by the scientific community will be modified in the light of new investigations. Still, there are certain theories, such as the theory of evolution, that have stood the test of time and are generally accepted as valid.

Date added: 2023-08-28; views: 634;