Terminology. Alice and Bob. The Relationship

The hard part of talking about trust, confidence or control is to getting the terminology straight. Trust has already 17 different meanings [McKnight1996] so it is not possible to casually introduce the concept and expect that everybody will end up with the same understanding. Even worse: every definition will potentially be both accepted and contested. Attempts to deliver the structured yet rich ontology of trust (e.g. [Quinn2006]) may come in handy.

Definitions of trust (here these should properly be referred to as confidence) usually highlight such elements as Alice's expectations regarding Bob and Bob's supportive action, adding sometimes aspects of Alice's vulnerability and Bob's independence. Those definitions tend to describe different aspects of confidence and tend to fall into defining one or more of the following categories: propensity, beliefs, behaviour, decisions, relationship, etc. The set of definitions offered here structures the problem from the perspective of a book where we are interested in Alice being able to make the proper assessment of her confidence in Bob.

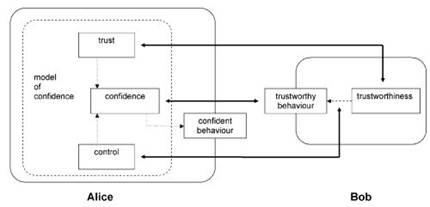

We will start from the initial scene again: Alice and Bob, each person thinking something and is behaving in some way (see Figure 1.1.).

Figure 1.1. Basic concepts

Alice. We are interested in Alice's assessment regarding her confidence in Bob, as this will presumably drive her behaviour. We are, however, not only interested in her decision alone: we would like to understand how Alice reached her decision - we would like to create a mental model of Alice, thinking process in an expectation that such a model will help us in understanding others (and will be potentially implemented in some technical devices).

We will define confidence as the belief that the other party (Bob) will behave in a way that is beneficial and desired for the first party (Alice), e.g. supporting Alice's goals, helping her or refraining from actions that may harm her. Confidence is Alice's internal state of mind, an expectation, and is not directly visible to the external observer. Only Alice can tell us how much confidence she has in Bob. In order to establish a link with measurable statistics, we will define confidence in terms of probability, but as confidence is bound to Alice's belief, such probability will be subjective - we are concerned here strictly with what Alice thinks.

Confidence is one's subjective probability of expectation that a certain desired event will happen (or that the undesired one will not happen), if the course of action is believed to depend on another agent

Confidence, apart from being a belief, can also be interpreted as a uni-directional relationship that is controlled by Alice. Alice can initiate, maintain, change the level of intensity or terminate this relationship through her own cognitive process (even though we expect that Alice will take into account certain reasonable evidence while doing it). Also in this sense confidence is subjective, as it is only Alice's cognition that makes her confident in Bob. We will see later that Alice can even misinterpret her knowledge only to continue such a relationship, no matter what Bob is doing.

We will use the following notation to describe confidence as a relationship (1.1):

where:

Alice - the agent (person) that is confident

Bob - the agent (person) that Alice is confident about

subject - the frame of discourse; action or state that Alice is concerned about

time - temporal limits of discourse

If this is not confusing, we can leave the subject and time blank, which should be interpreted as a current subject and current time (present in current considerations).

Alice's confidence is a belief, her cognitive state that emerged from certain mental process. We cannot learn about her confidence in other way than through her introspection, but we can reasonably guess how she thinks by inspecting our (and others) mental process. What we end up with is the model of confidence that attempts to explain how Alice (like all of us) thinks about confidence.

Her internal confidence should drive her confident behaviour, the externally and socially recognisable set of actions that clearly signals that she is confident about Bob. For example, she may without hesitation cross the street, thus demonstrating that she is confident that Bob will stop his car when needed. She may also cross the street for several other reasons, from being careless to being distressed.

Therefore we must be careful to differentiate between confidence (as a belief) and confident behaviour. Alice may be confident about Bob but this may not be visible in her behaviour. For example, when she request a verification of certain work that Bob has done, she may be confident about the outcome, but she may be obliged to conduct such verification.

Further, she may express confident behaviour even though she is not confident about Bob. Deutsch [Deutsch1973] provides a long list of motivations that may cause Alice to behave in a confident manner, even though her beliefs may contravene our expectations regarding confidence. Alice may look confident because of despair (choosing it as the lesser of two evils); out of social conformity (if she does not look confident then she may fear social ostracism); due to her innocence (not knowing enough about a cruel world); she may follow her impulsiveness and emotions; she may consider confidence a social virtue that should be demonstrated; she may be masochistic - so that she defies our perception of her utility or finally she may like risk and gambling.

Trust is a part of Alice's belief that leads to confidence in Bob. Another part of the same process is control. We will discuss how they interact later throughout the book. Neither trust nor control is directly visible through Alice's actions, but they are both embedded in her confidence that can potentially be observed through her behaviour.

Even though they are never directly visible, we will see that there are interactions where Alice's behaviour is mostly motivated by trust and interactions where trust and control go hand in hand - or where control prevails. We will not yet introduce definitions of trust or control as they can only be defined in relation to each other and to other elements of the model.

Bob. Let's look at Bob. He may be inclined to support Alice in her undertaking (e.g. by stopping the car) because of his intentions - his nature, so to speak. His internal intentions regarding Alice within the scope of this transaction will be called trustworthiness, in a slightly confusing manner (because trustworthiness, similarly to trust is overloaded with meanings).

Trustworthiness is a cognitive state that Bob can manage, with or without Alice. Bob can decide to do something or not, whether he is disposed to help, Alice in particular or whether he is ready to help everybody through certain actions or finally whether he would like to do it now but not later.

Again, what Bob does is not always what he thinks. In particular, Alice would like him to express trustworthy behaviour - simply to help her by providing what she wants (stopping the car, etc.). From our perspective this is what we can observe (as we do not have access to Bob's intentions). Bob's behaviour may not always be the result of his trustworthiness. He may exercise certain scenarios that may make Alice confident in him even though he does not intend to support her - the common salesman ploy.

He may also suppress his trustworthy behaviour despite his trustworthiness, e.g. to scare Alice away. The most important thing for us is that Bob can be driven to expose trustworthy behaviour (which is beneficial for Alice) even if his trustworthiness is not up to it.

There is a potential gap between Bob's intentions (his trustworthiness) and his actions. The explanation for such a gap lies in the control element - Bob may not be willing to support Alice, but he can somehow be forced to do it. For example, Bob may stop and let Alice go not because he is of a particularly good spirit but because he is afraid of possible consequences of not stopping, e.g. in a form of a fine.

The Relationship. Let's now consider the complete picture of Alice and Bob (Figure 1.1) again. We can see that Alice can maintain certain levels of trust and control, collectively leading to her confidence. How does it match Bob?

We know that trust can have several interpretations. Specifically [Baier1986], we should distinguish between trust as behaviour (Alice is behaving in a way that signals her trust in Bob) and trust as belief (Alice believes that Bob is worth her trust, i.e. he is trustworthy). Here, trust is used in the latter meaning.

Bob keeps his internal state of trustworthiness, his intentions regarding this particular interaction. Whatever the reason, Bob's good intentions are potentially (but only potentially) visible through his trustworthy behaviour. As has been already stated, Bob can also be forced to behave in a trustworthy manner regardless of whether he is trustworthy or not. Alice can rely on one or more of her instruments of control to enforce desired behaviour. In this case Bob's trustworthy behaviour is an effect of both his trustworthiness and Alice's control.

Note that Bob's behaviour relates to the overall confidence, not only to trustworthiness and it should properly be called 'confidence-signalling behaviour'. However, following the prevailing terminology that can be found in literature, we will stay with the less exact but more familiar term of trustworthy behaviour.

We are interested in Alice's transactional assessment about confidence and her decision to proceed (or not) depending on whether she is confident enough about Bob. The key element therefore is her ability to estimate Bob's intentions. If she over-estimates him, she is risking failure, but if she under-estimates him, she is missing an opportunity. What she needs is a correct estimate.

While looking at both the model and the relationship, we can see that Alice's estimate of trust in Bob should match his trustworthiness. We have provisionally defined trust as Alice's expectation that Bob will support her in the absence of any control element - in line with the way we defined Bob's trustworthiness.

Alice's estimate of control over Bob should therefore match the difference between his trustworthiness and his trusting behaviour, i.e. it should explain Bob's behaviour that is not driven by his intentions. Consequently, Alice's confidence in Bob should become an estimate of his trustworthy behaviour.

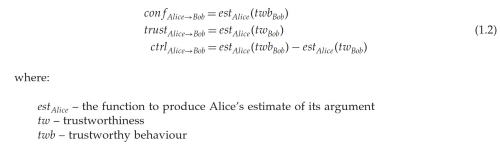

Assuming that we can consistently assign certain numeric values to all elements of the model (preferably with identical semantics), we can express the relationship as follows (1.2.):

Note that we did not introduce the concept of 'controllability' similar to trustworthiness, i.e. we do not assume that Bob has a certain predilection (or resistance) to be controlled. We can deduct the existence of control only as a difference between trustworthy behaviour and trustworthiness.

Defining all elements of those formulas in terms of subjective probability, we have:

- Trust is an estimate of a subjective probability of certain desired course of actions in the absence of control.

- Control is the difference between the estimate of the subjective probability of trustworthy behaviour and trust.

Thus, trustworthiness is Bob's internal intention while Alice does not exercise any of her control instruments. It is 'Bob on his own', without any pressure from the outside. It is Bob's internal disposition to support Alice. By contrast, Bob's response to control is visible only if Alice exercises one of her instruments of control. Such a response is a result of Alice's action so that it does not exist as Bob's mental state before Alice uses her instruments.

The amount of control does not depend on Bob so that is not part of his description. Alice, if not bound by complexity, can exercise any amount of control and Bob will eventually behave in the expected manner.

Date added: 2023-09-23; views: 768;