Insects. Plagues and Pests

Insects (arthropods with three pairs of legs) are small, but they are the most numerous and most diverse creatures on the planet. If an alien intelligence were to land on Earth, charged with surveying its living creatures with limited time and limited resources, it could not do better than study just beetles, dismissing everything else as sampling error.

Despite their small size, insects have had a powerful influence on the world and on humans' relationship with the environment. They have been able to achieve this influence because of their vast numbers, their versatile adaptability, and their mind-numbing diversity.

Insects are thought to have been largely responsible for the explosion of angiosperms (flowering plants) in the Cretaceous period (145-65 million years ago), a basic fact that influences every aspect of the present environment on Earth. These are now the dominant plants on the planet and the most important feature of virtually any landscape in the world.

The evolution of flowers has been intricately linked to the evolution of the insects that are attracted to pollinate them. And since that time, too, unimaginable numbers of insect herbivores have mounted a continuous and prolonged attack on plants, bringing to bear a heavy selective load on the evolution of plant defenses, both chemical and physical.

Looking around at the greenness of the world, it is easy to imagine that plants are thriving more or less everywhere and that the nibblings of plant-eating insects have only a minor effect on plant growth. But this belies the fact that these plant-eaters are kept in check by predatory species in an intricate ecological web. The effects of plant-eating insects are best noticed when this web is disrupted.

The gypsy moth (Lymantria dispar) is one of many alien species that has been imported into the United States (ironically it was deliberately introduced to test its suitability for silk production). Having left its normal predators and parasites behind in Europe, it has become a serious forestry pest, defoliating vast areas of conifer forest. Likewise, but for the benefit of ecology, the deliberate introduction of the prickly- pear moth (Cactoblastis cactorum) into Australia cleared 24.2 million hectares of the normative prickly-pear cactus (Opuntia), which had become an invasive weed squeezing out the native flora.

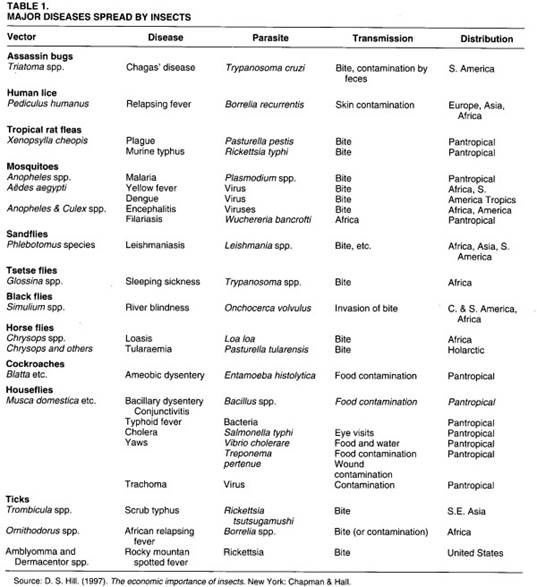

Plagues and Pests. Insects have most profoundly influenced the environment through their depredations on agricultural crops, forests, domestic food stores, and farmed animals and by their implication in the spread of human and animal disease. (See table 1.)

As soon as early humans changed from being nomadic hunter-gatherers to settled agriculturalists, insects were on hand to take advantage of the ecological niches provided to them. Crop monocultures (forest trees as well as agricultural plants) made it easy for some insects to become major economic, even famine-inducing, pests.

Plagues of locusts may have biblical overtones, but they still occur today, and they are still as dramatic and as terrible. Almost all groups of insects have plant-feeding species, and these are considered pests when feeding on cultivated plants.

Other well-known agricultural pests include Colorado beetle (Lep- tinotarsa decemlineata) on potato, vine phylloxera (Viteus vitifoliae) on grapevine, Japanese beetle (Popillia japonica) on horticultural plants, maize weevil (Sitophilus species) on rice and maize, Mediterranean fruit fly (Ceratitis capitata) on soft fruit, cabbage white butterflies (Pieris species) on brassicas (herbs such as cabbage), and bollworms (Diparopsis and Earias species) on cotton. The list is seemingly endless.

Less-obvious but equally devastating attacks come from a wide variety of insects feeding on stored products in silos, warehouses, shops, and homes. Some of the most damaging species are weevils and other beetles that "in nature" eat seeds and nuts, but have adapted to feed on the bountiful surplus of stored grain. Although difficult to measure worldwide, it is estimated that 30-40 percent of all crop produce (currently valued at more than $300 billion) is destroyed by insects, either in the fields or in postharvest storage.

Worse than the damage done to stored products is the damage done to homes constructed of wood. The words termite and woodworm are shot through with the base associations of destruction and worthlessness. The notion that homes, hospitals, universities, libraries, temples, and all the other tokens of a civil society are under gnawing attack from wood-boring insects is a powerful and sobering indictment of what is often viewed as a menacing, malevolent insect nation.

Timber continues to evoke feelings of mellow warmth and naturalness as a construction material, but its natural limitations, including its vulnerability to attacks by insects, have led to the use of impervious stone and glass, and later concrete and steel. The imposing strength of important architecture, from cathedrals to castles, was driven by a response to these attacks and the natural decay of wood, thatch, and other previously available materials.

Date added: 2023-10-02; views: 717;