Doing Lexicography in Electronic Age

Tono (28) predicted the advantages of online media using machine translation, saying “Electronic dictionaries have great potential for adjusting the user interface to users’ skill level[s] so that learners with different needs and skills can access information in... different way[s].’’ (p. 216).

First of all, one must note that electronic dictionaries have developed based on a healthy integration of developments in computerized corpus linguistics and modern technology, used to enhance learning in many fields, particularly computer-assisted language learning (or CALL) or computer-mediated communications (CMC).

Laufer and Kimmel (2) provide a clear summary of this field, noting that

If the consumer is to benefit from the lexicographer’s product, the dictionary should be both useful and usable. We suggest a definition of dictionary usefulness as the extent to which a dictionary is helpful in providing the necessary information to its user. Dictionary usability, on the other hand, can be defined as the willingness on the part of the consumer to use the dictionary in question and his/her satisfaction from it. Studies of dictionary use by L2 learners ... reveal that dictionary usefulness and dictionary usability do not necessarily go hand in hand. (pp. 361-362)

Laufer and Levitzky-Aviad’s (4) study recommends working toward designing a bilingualized electronic dictionary (BED) more clear and useful for second language production. Whereas conventional bilingual L1-L2 dictionaries list translation options for L1 words without explaining differences between them or giving much information about how to use various functions, Laufer and Levitzky- Aviad (4) examined the usefulness of an electronic Hebrew-English-English (L1-L2-L2) minidictionary designed for production.

Their results demonstrated the superiority of fully bilingualized L1-L2-L2 dictionaries and some unique advantages ofthe electronic format. Their literature review provides a good overview of this field:

Surveys of dictionary use indicate that the majority of foreign language learners prefer bilingual L2-L1 dictionaries and use them mainly to find the meaning of unknown foreign (L2) words (Atkins 1985; Piotrowsky 1989). However, if learners writing in L2 need an L2 word designating a familiar L1 concept, they do not readily turn to an L1-L2 dictionary for help. The reason for this may lie in a serious limitation of most L1-L2 bilingual dictionaries.

They rarely differentiate between the possible L2 translations of the L1 word, nor do they provide information regarding the use of each translation option... An electronic dictionary can fulfill the above requirements since it can combine the features of an L2-L1bilingual dictionary, an L1-L2 bilingual dictionary and an L2 monolingual dictionary.

The advent of electronic dictionaries has already inspired research into their use and their usefulness as on-line helping tools and as contributors to incidental vocabulary learning. The built in log files can keep track of words looked up, type of dictionary information selected (definition, translation, example, etc.), the number of times each word was looked up, and the time spent on task completion. (pp. 1-2)

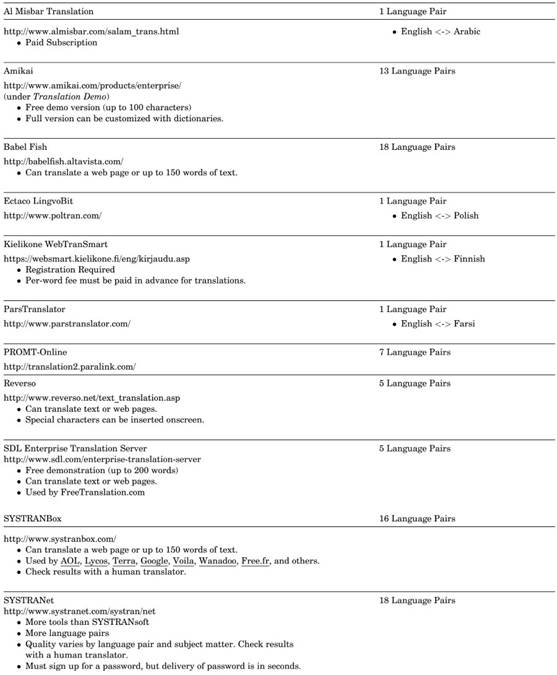

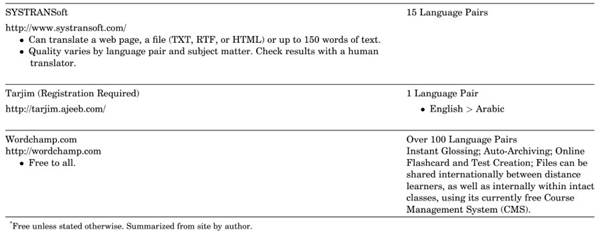

Although most electronic dictionaries do autoarchiving of any new words by means of their history search function, most online dictionaries do not have a means of tracking student use, except for programs like Wordchamp.com or Rikai.com, which give students a way to archive words they have double-clicked. These words may later be seen, printed, and reviewed. In fact, Wordchamp.com, by far the most sophisticated online electronic dictionary and vocabulary development program, allows users to make online flashcards with sentence examples and links to online texts where target words are found in context.

It can also automatically generate about 10 types of online vocabulary quizzes and provides a free course management system (CMS) for monitoring students’ work online. Wordchamp’s Webreader provides the most versatile online glossing engine known, already for over 100 languages, with more being added regularly.

Teachers need to show learners how to best integrate the use of such portable and online dictionaries to make them maximally effective for their language development, in both receptive and productive aspects. Chun (12) noted that learners who could read online text with ‘‘access to both internally (instructor-created) glossed words as well as externally glossed words... recalled a significantly greater number of important ideas than when they read an online text and had access only to an external (portable electronic) dictionary’’ (p. 75).

Loucky (29) also examined how to best maximize L2 vocabulary development by using a depth of lexical processing (DLP) scale and vocabulary learning strategies (VLSs) taxonomy together with online CALL resources and systematic instruction in the use of such strategies. It used 40 of the 58 VLSs identified in Schmitt’s earlier taxonomy.

An electronic dictionary use survey (see Appendix) was designed to solicit information about how students used various computerized functions of electronic or online dictionaries at each major phase of lexical processing to help learners maximize processing in the following eight stages of vocabulary learning: (1) assessing degree of word knowledge, (2) accessing new word meanings, (3) archiving new information for study, (4) analyzing word parts and origins, (5) anchoring new words in short-term memory, (6) associating words in related groups for long-term retention, (7) activating words through productive written or oral use, and (8) reviewing/recycling and then retesting them. Portable devices or online programs that could monitor and guide learners in using these essential strategies should be further developed.

In Loucky’s (7) findings, despite being one grade level higher in their proficiency, English majors were outperformed on all types of electronic dictionaries by Computer majors. The author concluded that familiarity with computerized equipment or computer literacy must have accounted for this, and therefore should be carefully considered when developing or using electronic dictionary programs of any sort for language or content learning.

His study compared vocabulary learning rates of Japanese college freshmen and functions of 25 kinds of electronic dictionaries, charting advantages, disadvantages, and comments about the use of each (for details, see Loucky (6) Table 1 and Appendix 3; Loucky (8) Tables 1 and 2. For a comparative chart of six most popular EDs for English<->Japanese use, see www.wordtankcentral.com/ compare.html).

Table 1. Comparative Chart of Some Translation Software

Generally speaking, language learners prefer access to both first and second language information, and beginning to intermediate level learners are in need of both kinds of data, making monolingual dictionaries alone insufficient for their needs. As Laufer and Hadar (30) and others have shown the benefits of learners using fully bilingualized dictionaries, the important research question is to try to determine which kinds of electronic portable, software, or online dictionaries offer the best support for their needs.

Grace (31) found that sentence-level translations should be included in dictionaries, as learners having these showed better short- and long-term retention ofcorrect word meanings. This finding suggests a close relationship exists between processing new terms more deeply, verifying their meanings, and retaining them.

Loucky (32) has researched many electronic dictionaries and software programs, and more recently organized links to over 2500 web dictionaries, which are now all accessible from the site http://www.call4all.us///home/_all.php?fi=d. His aim was to find which kind of EDs could offer the most language learning benefits, considering such educational factors as: (1) better learning rates, (2) faster speed of access, (3) greater help in pronunciation and increased comprehensibility, (4) providing learner satisfaction with ease of use, or user-friendliness, and (5) complete enough meanings to be adequate for understanding various reading contexts.

As expected, among learners of a common major, more proficient students from four levels tested tended to use EDs of all types more often and at faster rates than less language-proficient students did. In brief, the author’s studies and observations and those of others he has cited [e.g., Lew (3)] have repeatedly shown the clear benefits of using EDs for more rapid accessing of new target vocabulary.

They also point out the need for further study of archiving, and other lexical processing steps to investigate the combined effect of how much computers can enhance overall lexical and language development when used more intelligently and systematically at each crucial stage of first or second language learning.

Regular use of portable or online electronic dictionaries in a systematic way that uses these most essential phases of vocabulary acquisition certainly does seem to help stimulate vocabulary learning and retention, when combined with proper activation and recycling habits that maximize interactive use of the target language. A systematic taxonomy of vocabulary learning strategies (VLSs) incorporating a 10-phase set of specific recyclable strategies is given by Loucky (7,29) to help advance research and better maximize foreign language vocabulary development (available at http://www.call4all. us///home/_all.php?fi=../misc/forms).

A summary of Laufer and Levitzky-Aviad’s (4) findings is useful for designers, sellers, and users of electronic dictionaries to keep in mind, as their study showed that: ‘‘the best dictionaries for L2 written production were the L1-L2-L2 dictionaries... Even though the scores received with the paper version of the L1-L2-L2 dictionary were just as good, the electronic dictionary was viewed more favorably than the paper alternative by more learners.

Hence, in terms of usefulness together with user preference, the electronic version fared best’’ (p. 5). Such results should motivate CALL engineers and lexicographers to produce fully bilingualized electronic dictionaries (as well as print versions), specifically designed not merely to access receptive information to understand word meanings better, but also for L2 production, to practically enable students to actively use new terms appropriately as quickly as possible.

Date added: 2024-02-20; views: 640;