Computer Support for Context-Oriented Communication

In CSCL systems, the provided material can and has to be used to serve as context. For the design of CSCL systems, a design rationale for computer-supported communication is suggested that emphasizes the difference between communicative contributions and context as well as the tight interweavement of both. Hmelo-Silver, for example, mentions this requirement with respect to computer-supported, problem-based learning: ‘‘There needs to be a mechanism for the facilitator and other students to negotiate and discuss the contents of the whiteboards in an integrated fashion’’.

These requirements are fulfilled in systems that use annotations for the support of communication. The annotations (— communicative contributions) are related to learning material (— context). Discussions occur by annotating annotations. The design of communicative contributions in the form of annotations in CSCL systems is inspired by systems for joint creating and editing of text like CoNote, CaMILE or WebAnn.

All these systems focus on functionalities enabling annotations but do not support the linkage of fine-grained material (CoNote and CaMILE) or material that is added by the learners (WebAnn). Therefore, the material cannot be used flexibly as context. Two CSCL systems that follow the context-oriented communication theory are anchored discussions and KOLUMBUS.

In the following discussion, the main concepts for the support ofcontext-oriented communication and facilitation are explained by the example KOLUMBUS. KOLUMBUS is a Web-based CSCL system and should be viewed as one example for the class of CSCL systems that support asynchronous learning. The name is an acronym for a German term that stands for ‘‘Collaborative Learning Environment for Universities and Schools.’’ The concentration on only one system in this article offers the possibility to show interrelations between different functionalities and to add experiences with the described functionalities.

The crucial feature of KOLUMBUS is to support the segmentation of content into small units. This segmentation allow the learners a highly flexible intertwining of content as context with communicative contributions in the form of annotations. KOLUMBUS provides two different views of content. In the tree view, each item is represented as a node in a hierarchical tree-structure. To focus on relevant content, parts of the tree or the whole tree can be expanded or minimized. Furthermore, newly inserted items are indicated as new. Although the structure of a set of interrelated annotations represents a dialogue- oriented discussion thread, the hierarchical structure of the material depends of the logical relationships between its content.

By contrast to the tree view, the article view shows content in a visually more attractive and readable way. Here, different types of presentations are combined to form a single document. Within the paper view, KOLUMBUS supports the perception of meaningful structures built up on a didactical basis. The teacher is responsible for preparing material, arranging how the (initial) material is displayed in the paper view.

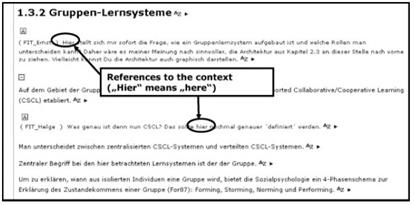

Didactically prepared material of the teacher can be used by the students as a starting point for their own research. In the paper view, it is also possible to expand or reduce the scope of displayed items and, therefore, to achieve an adaptable extent ofcontext as being necessary to facilitate communicative understanding. Figure 1 shows the menu that can be activated at every single item.

Figure 1. Communicative contributions in context

It allows users, for example, to add communicative contributions (in the form of annotations) or material. All these functions of KOLUMBUS are available in both types of representation (paper or tree view).

Both the tree view and the paper view can be used to work with an individual’s own material as well as with that of others. To differentiate between annotations and material, the tree view uses different icons, whereas the paper view employs different colors. In the paper view, the communicative character of annotations is increased by prefixing the annotation with the author’s name, which is similar to the convention with newsgroups. After switching from tree to paper view, annotations are hidden behind a nonintrusive symbol to offer the chance to assimilate the material first.

An advantage of the concept of the fine-grained item- structure is that communicative contributions can be directly linked to that part of the content to which they refer, and which therefore provides the relevant context. From this point of view, it becomes obvious that the definition of context depends on the communication act itself. Context is everything to which an annotation refers.

Figure 1 shows the paper view from a seminar in computer science: a title and some sections of material and two annotations (communicative contributions). Annotations are signed with an ‘‘A’’ and the name of the author in front. Because the communicative contributions are placed in the direct context, the author does not need to include hints for additional context. This leads to relatively short contributions and to the usage of direct references (in both annotations in Fig. 1, the word ‘‘hier’’ (German for ‘‘here’’) is used to reference the context).

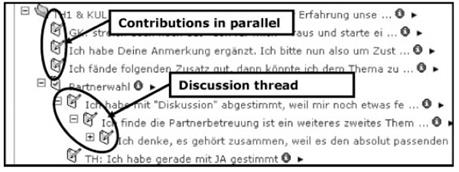

Asynchronous learning by communication is supported by the possibility of discussion threads that can be developed by annotating other participants’ annotations. These threads can be handled in the same manner as, for example, in newsgroups. Threads can occur in parallel; they can be expanded or minimized (as all items in KOLUMBUS).

Figure 2 shows an example in the tree view. Items are signed with the pencil and post-it icon. Since the tree view should only give an overview, just the beginning of the annotations (as well as text-based material) is presented in one row. The whole content can be read in a tool tip that appears with the mouse-over.

Figure 2. Discussions by using annotations

Experiences with KOLUMBUS (see Ref. 17 for details) revealed on the one hand that the integration of communication and work on material is an appropriate concept to support context-oriented communication and collaborative learning. The studies support the requirements derived from the context-oriented model of communication. Learning material serves as context and supports the communication.

The tight integration of communicative contributions in the form of annotations and segmented learning material helps in general the communicator to select the appropriate pieces of context information and the recipient to understand better the utterance of the communicator. However, problems with the detection of new communicative contributions occur when the content structure is growing very fast—this lead to the necessity for concepts like the annotation window.

This problem is also related to the question of an appropriate granularity. A fine granularity helps a communicator to relate his expression exactly to the context but results in a fast-growing content tree. A coarse granularity, on the other hand, leads to a manageable content structure but does not offer the possibility to relate the annotation to exact context information. The granularity of paragraphs seems to be appropriate for the joint development of texts.

On the other hand, they emphasize improvements concerning the handling of communicative contributions in the form of annotations and their interweavement with material as context. These improvements deal with the following topics:

Differentiation between Organizational and Content- Related Annotations.Two requested types of annotations are available. A new annotation has the property ‘‘content- related’’ by default, but it can be labeled as ‘‘organizational’’ by the author. The different labels correspond to different colors in all views that help the reader to differentiate the annotations at a first glance. These categories are context information that helps the recipient to estimate the aim of the communicative contribution.

The second round of studies revealed many incorrect typed contributions with the default entry ‘‘content-related’’ although they include only organizational issues. This finding shows that the participants often did not reflect the type of their contributions and the recipients had the major burden to reconstruct the real aim of the annotation. The existence of a default entry is misleading because the entry suggests information that is not given by the communicator.

On the other hand, the recategorization showed that both types are relevant for collaborative learning. This is especially true in long period scenarios that do not include weekly face-to-face meetings because all organizational issues are discussed with the help of the CSCL system, and this requires organizational contributions.

The studies showed that in short period scenarios the organizational effort is not that high, and in a setting with weekly face-to- face meetings, a lot of organizational issues were discussed in the meeting. To keep all these arguments in mind, the usage of the two categories content-related and organizational without a default entry are proposed. Thus, a context is not suggested that is not also given.

Usage of Keywords as Context Information.Keywords are a summary of the communicative contribution. The communicator labels the contribution with words that are important for him and that help the recipient to estimate the content. A keyword for the annotation can be added similarly to the subject field of an e-mail. This keyword summarizes the annotation and helps the reader to recognize the content of the annotation at a glance. The keyword as well as the author and the date are prefixed to the annotation itself.

The results of the studies revealed that keywords are more often used when the previous annotation was written a long time before. In timely nearby contributions, the communicator seems to suppose that the recipient can conclude the context in the form of the appropriate discussion thread. We conclude that keywords are a helpful kind of context information that has to be included in a CSCL system—especially in long period asynchronous discussions. A reply-entry (like in e-mail applications) could support a communicator in automatic filling the keyword when contributing to an already existing discussion thread.

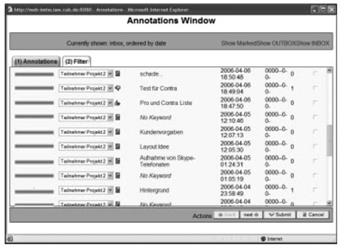

Chronological View of Communicative Contributions.Another technical improvement contains an annotation window as an additional view (see Fig. 3). This window is comparable to an e-mail inbox that gives an overview of all annotations in the chosen content area. The entries in the list are links that guide the user to the annotation’s position in the integrated view. The list can be sorted by different metadata (e.g., author, date, and subject) and filtered (e.g., only content-related annotations). This window helps to perceive the annotations in chronological order and to be aware of new annotations.

Figure 3. Annotation window as an overview of new contributions (names are hidden due to provacy reasons)

Studies revealed that the usefulness of the annotation window depends on the underlying learning scenario. In scenarios with the joint creation of material by the group of learners, the content structure is growing very fast and the detection of new annotations ‘‘somewhere’’ in this structure becomes difficult. For these scenarios, an annotation window comparable to an e-mail in- and outbox gives an overview of communicative contributions and serves as a helpful awareness feature.

Date added: 2024-03-07; views: 550;