Ezra, the Shrine of St George, 515 ad. Seleucia Pieria, Martyr-shrine of the Late Fifth Century

The martyr-shrine, as it developed through the centuries, took on a variety of forms showing keen inventive powers exercised within the formula set by pagan tombs. The square, the circle and the octagon, alone or in combination, served as the basis for most of them, but the 'tetraconch' also was favoured, its four apses projecting each from one side of a square that was usually indicated only by four robust corner-pillars.

A rather ambitious example of the more advanced type of martvr-shrine is provided by the sanctuary of the saints Sergius, Bacchus and Leontius at Bosra, which served also as the cathedral of the local bishop. This building, which an inscription conveniently dates to 512 ad, is essentially a square from which three apses project. The large central apse, of octagonal shape outside but a flattened semicircle within, is flanked by the two smaller ones, square-ended but semicircular inside the thick walls.

Whether these should properly be thought of as relic-chapels or as sacristies, two lesser rooms are squeezed between them and the central apse, thus making the east end of the church a fivefold arrangement of interlocking members connected by substantial doorways. The square nave of the cathedral is converted internally, with the aid of four niches rounding off the comers, into a circle. Windows abound, and the circle itself acts as an aisle flowing around a quatrefoil composed of piers and columns. This central part of the building seems to have been covered in wood while the aisle was roofed, in Syrian fashion, with large slabs of stone.

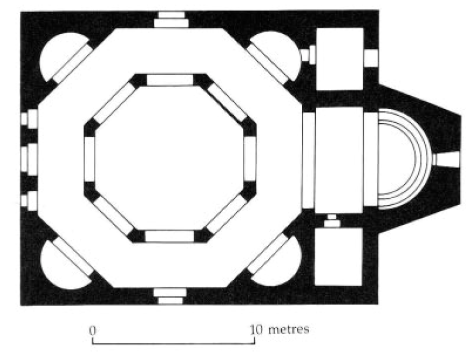

A variant on this complex but balanced pattern is evident in the shrine of 'the triumphant, holy martyr Ceorge' at Ezra, also in the Hauran district of Syria, and bearing the date 515 ad (fig. 80). Here the east end consists of a semicircular chancel with a solitary window piercing exceptionally thick straightened walls. In front of the semicircle lies a rectangular space, well adapted for celebrations of the liturgy, with a subsidiary room at each side. The square nave, once more enriched with semicircular recesses in the massive walling of the corners, is shaped internally as an octagonal aisle enclosing not a quatrefoil, as at Bosra, but another octagon. This internal octagon extends upwards to serve as the drum of the cupola.

8o. Ezra, the shrine of St George, 515 ad: ground-plan

Greater stability is secured by arranging the top two courses of stone in the drum so that the eight sides are doubled to form sixteen and then doubled again to make up thirty-two, thus easing the transition from octagonal to circular form. The cupola itself is eggshaped, perhaps under the influence of precedents drawn from Central Asia, while the small roundheaded windows at the base of the cupola are an early essay in the type of clerestory adopted with such impressive effect at Santa Sophia. St George's, Ezra seems to have been a dark building with few windows but with doorways to north and south as well as the bolder feature of a triple entrance marking the west end. The general pattern suggests the influence of early baptisteries, which often consisted of an octagon surmounted by a dome.

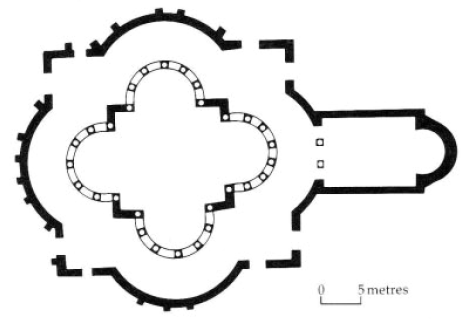

One other example of bold design, having much in common with S. Lorenzo in Milan, is the martyr- shrine recently unearthed at Seleucia Pieria, just outside Antioch (fig. 81). Constructed partly of limestone, partly of rubble, it has a chancel floor of marble slabs and much gailv-patterned mosaic elsewhere. The basic form of this buiding is that of two quatre- foils, one inside the other. The inner quatrefoil has well-marked rectangular corners suggesting a square from which, in perfect regularity, columns arranged as a semicircle protrude on all four sides. The external walls also are squared off, on three sides, with rather flattened semicircles. These give the building a diameter of some 37 metres. On the east side, and extending for over 15 metres, is an addition shaped like a little basilica, with rectangular hall and a shallow apse contained within thick walling. Along lines such as these the Syrians developed their national style of church architecture, making use of materials to hand, with sensitive regard to practical needs and artistic harmony.

81. Seleucia Pieria, near Antioch: a recently discovered martyr-shrine of the late fifth century

The remote country eastward, the mountainous region of the Tur Abdin and the neighbouring territories of northern Mesopotamia, formed a debatable land both politically and ecclesiastically. The emperor Jovian ceded Nisibis to Persia in 363 ad but the redrawn frontier was an unstable one. Generally speaking, the Persians to the east came to provide a refuge for the Nestorians, while the Melkites, the 'King's men' of the Byzantine Orthodox church, prevailed in the west. These divisions, however, were without effect on the style of church architecture, which may be divided into two groups: the parochial and the monastic. The parochial, village churches are unpretentious buildings, longitudinal in form with an entrance on the south side and sometimes a small oratory free-standing nearby. A brick barrel vault covers the whole area of the church, gaining stability from arcades built close up against the side walls. Dating is uncertain and many of these churches are nowadays referred to the period shortly after the Arab conquest in 640 AD.

Examples of the second or monastic type of church are less frequent but distinctive in character. Nearly square in plan, they customarily have three separate chambers, or sanctuaries, attached to the east and a narthex to the west. Low, heavy arcades line the walls, forming the basis of the barrel vault. The only one of these churches securely anchored to a relatively early date is that in the monastic complex of Mar Gabriel at Qartamin. This appears to owe its prestige, as well as its now fragmentary mosaics, to the patronage of the emperor Anastasius round about 512 ad. The church lies broadways on, in what is sometimes described as the Babylonian fashion. Squat and ill-lit beneath its vast tiled roof, it nevertheless gives a firm impression of Syrian stateliness and power.

Armenia, where, under the influence of Gregory the Illuminator, Christianity was recognized as the official religion by King Tiridates III not later than 295 ad, might be expected to offer a distinctive style of Christian architecture. This is indeed the case, though existing churches all display evidence of renovation dating from the seventh century or later. Beneath the alterations, however, a structure such as Etchmiadzin still retains primitive features. It seems that here the fourth-century church was originally built as a square, covered by a cupola based on four pillars and enclosing an eastern apse.

This form, practical yet impressive, may owe something to the royal Hall of Audience transformed into a shrine appropriate to the victorious Christ. A hundred years or so later the rectangular lines were modified by semicircular extensions on all four sides. The church at Ereruk, which may be as early as the beginning of the sixth century, shows that the Armenians were also perfectly capable of constructing a basilica on the Syrian model, with barrel vaults to nave and aisles, a tower at each end of the faqade, and round-headed windows moulded in flowing lines.

Date added: 2022-12-11; views: 1039;