Church Buildings in Asia. Imperial Influences and Practical Needs

Early Christian architecture is an imitation, and little evidence exists of any particular desire to hammer out a novel and distinctive style. The forms adopted had the advantage of being traditional and familiar, in addition to being well tested for usefulness and aesthetic appeal. Moreover, they were enriched by overtones of symbolism and mystical meaning which the Roman emperors, both pagan and Christian, turned to advantage in the design of official buildings and which, by an easy transference of association, gave a touch of supernatural dignity to churches.

Thus the palace, particularly the palace-fortress of the kind built by Diocletian at Salona, came to typify a dominion which reproduced on earth the government of the Universe exercised by the Almighty. As it is not easy to take in a whole palace-fortress at a glance, however, and still more difficult to draw a neat likeness of it, the palace gateway is used, as part for the whole, to represent power and authority.

At the very beginning of the Christian era, a coin struck for the emperor Augustus at Merida in Spain shows a fortified portal with battlements, two large entrance doors and a square tower at each side. This might be no more than a hint of military strength expressed in terms of a contemporary fortress, but later on, particularly in the more barbarous outposts of Empire, figures representing Plenty or Good Fortune were added to recall that the triumphant arrival of the emperor at the city-gate was accompanied by a godlike bounty of peace and prosperity.

Rather more frequently the arcade over the main entrance was stressed as being the gallery from which the emperor looked down to receive the crowd's applause. Whatever the precise steps in the argument may have been, the arcade came to suggest the eternal abode of a divine being. One illustration of this is the Ravenna mosaic which shows Theodoric's palace equipped with an elegant arcaded gallery in imitation of the pattern laid down at Salona where a formal arcade over the ceremonial entrance contained statues of the gods. Christian opinion found it easy enough to connect the formalized gateway with ideas of kingship, human or divine, by reason of passages in the Bible where the relationship is clear. In the Old Testament history kings regularly sit, where their subjects can see them, in the entrance court before the palace, as when

the king of Israel and Jehoshaphat the king of Judah sat each on his throne, arrayed in their robes, in an open place at the entrance of the gate of Samaria

while mysterious hints, suggesting not merely the victorious warrior but the universal Sovereign, echoed in the Psalmist's words: 'Lift up your heads, О ye gates, and be ye lift up, ye everlasting doors, and the King of glory shall come in.' It is therefore not surprising that entrance portals are commonly displayed on the coins of Constantine and his sons (fig. 75) together with such emblems as the 'bright morning star' and slogans, of which Providentia was the most popular, which implied that members of the imperial house kept watch over the welfare of the far-flung Empire.

75. City-gate coins: a. Constantine: Arles mint; b. Gordian II: Marcianopolis mint

The significance, on coins, of the royal house with towers at the corners was enhanced when the towers were capped with little domes or when, as on a series of coins struck for Diocletian and Constantine, the faqade was decorated with a row of turrets bearing little domes. For dome and cupola had their emblematic value as indicating the vaulted canopy of Heaven, the 'blue dome of air' as poets instinctively describe it. Under the influence, perhaps, of the great Temple of Bel at Palmyra, the dome was adopted not merely as a convenient architectural device but as signifying the universal sway of the Almighty Creator and of the emperor who acted as his visible embodiment. Here again a touch of symbolism joined with custom and the practical needs of the worshipping community to produce the forms of Christian architecture.

The pattern of church-building in Asia Minor was to a large extent shaped by the creative vigour and restless enthusiasm of Constantine and other members of the imperial house. Not only were the sacred sites of Palestine furnished with magnificent shrines but, as Eusebius records, other cities also benefited. Among them was Antioch, where Constantine constructed a church 'unsurpassed for size and beauty'. This has now disappeared, but in the fourth century it was

surrounded by an enclosure of considerable size, within which the church itself rose to a great height. It was octagonal in shape and surrounded on every side by a number of halls, courts and two-storeyed apartments: everywhere there was lavish adornment of gold, brass and other materials of the most costly kind.

This was not the cathedral of Antioch but rather the palace-church, testifying by its splendour not only to the glory of God but to the emperor’s magnificence.

Further south, at Baalbek, a city renowned for the vigour of its pagan cults, the emperor constructed a church of 'great size and splendour' and arranged for the clergy to be housed nearby. The two particularly powerful influences were the Church of the Holy Apostles at Constantinople and the rotunda of the Holy Sepulchre, and it was apparently a model of the former that the empress Eudoxia brought, together with a present of marble columns, for the men of Gaza to copy in 401 AD.

Along with the influences exerted from the capital over much of Asia went a preference for classic forms of architecture carried down as a legacy from the Hellenistic age, while the long coastline with its many harbours favoured the free import of both craftsmen and materials. Inland, however, and particularly in the remote mountainous districts, a down-to-earth rustic style prevailed. The early churches, in Asia Minor as elsewhere, fall into two distinct types, adapted for different purposes.

There is the basilica, the ample rectangular hall suitable for the celebration of the liturgy in the presence of relatively large numbers of people, and there is the martvr-shrine, circular or octagonal, built around a sacred spot. Similar needs require similar forms, and the basilica throughout Asia differed little in essentials from, indeed closely resembled, the basilican structures of the West. Two special features are, however, characteristic of the basilicas of Asia Minor in the fourth and fifth centuries.

The first of these is the ambo which not seldom obstructed the nave. The term 'ambo' is derived from the Greek word for a 'raised-up place' or reading desk, resembling the ‘pulpit of wood' from which Esdras, the 'priest and reader of the Law', declaimed the Old Testament Scriptures to the multitude assembled in the 'broad place before the porch of the temple.

In the West, as for example in sixth-century Ravenna, the ambo is an attractively carved box with steps leading up to it—rather like an English pulpit —but in the East it often became an altogether more elaborate affair. In Justinian's rebuilding of S. Sophia at Constantinople the ambo was mounted by two flights of stairs, running from opposite sides. Constructed of the rarest marbles and decorated with gold, it was upheld by marble columns and had at the top of the stairs sufficient space to allow for an emperor's coronation while there was room for a close-packed choir beneath.

The ambo at S. Sophia was exceptional, like the vast building itself, but in earlier and less pretentious churches, particularly in Syria, a stone ambo of horseshoe shape occupied a substantial part of the central nave. Set upon a platform and sometimes approached from the east by a raised pathway, it was used for readings, sermons, announcements and hymn-singing, with the deacon standing before it to ensure liaison with the people clustered in the aisles.

Secondly, the apse, or semicircle reserved for the clergy, was developed in a variety of ways. It might project eastwards and be roofed with a half dome; but far more often, at first, it was enclosed within the rectangle of the church and flanked by two chambers known as pastophoria, or sacristies. It was customary to refer to these as prothesis and diaconicon, that is to say the place for making ready the eucharistic offering on the north side and, to the south, the vestry, where the deacons kept offerings, books and church treasure. But, at least from the beginning of the fifth century, the two chambers came to be contrasted with one another. The north side continued to serve as a sacristy but the southern room, distinguished by a more elaborate doorway, was clearly used on occasion as a chapel containing the honoured relics of martyrs. The later and more elaborate churches of Asia Minor show considerable freedom of design, and sometimes there are three apses projecting eastwards, the central apse flanked by semicircles which terminate the side chambers.

Writing of Palestine about 330 ad, the historian Eusebius, using vague and perhaps exaggerated terms, notes that the remains of martyrs,

placed in splendid church buildings and in sacred places of prayer, were given to the people of God that they might honour them in unceasing remembrance.

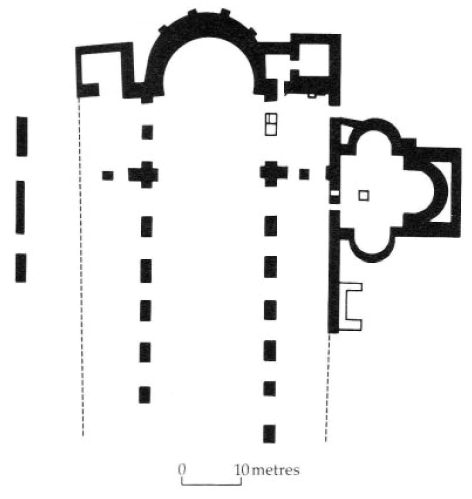

This might imply no more than an early form of medieval practice whereby a particular area within a church was reserved for the cult of a local martyr. More frequently the shrines were separate, standing alone or perhaps forming part of a group of buildings. The shrine of St Euphemia at Chalcedon, for instance, was a rotunda with galleries looking down onto a central hall. Although an independent structure, it was attached to the north side of a basilica and entered through that church. The same is true of the martyrium of St Leonidas at Ilissos, near Athens, where the shrine, rectangular in outline, occupies the corner between nave and transept of the basilica, while a church at Corinth (fig. 76) has, attached to its south wall, a large martyrium of trefoil shape.

76. Corinth: ground-plan of church with trefoil martyr- shrine annexed

The independent martvr-shrines, anyhow in fourth-century Asia Minor, were constructed according to the principles and forms of classical sepulchres, as freely adapted by Constantine to mark the holy places of Jerusalem. Such shrines, whether round, octagonal or cross-shaped, displayed a solemn, monumental character. They were places of pilgrimage where, often enough, the relics were kept in tombs of sarcophagus shape, equipped with funnels and an internal basin, so that oil could be poured over the bones and collected in small flasks for use by the pious as medicine. As the numbers of churchmen and the repute of the martyrs grew, the size of the buildings had to be increased also.

During the fifth century, when relics came to be freely bandied about from place to place, shrines to contain them were established in towns and began to serve more or less the same needs as the basilicas. The architectural form of the martyrium was therefore modified to enable the liturgy to be celebrated there 'decently and in order'. While, therefore, the basilica was tending to acquire a chapel for relics, the martyr-shrine changed into something closely resembling a parish church, and the distinction between the two quite different types of structure became blurred.

Date added: 2022-12-11; views: 1082;