Bethlehem, Church of the Nativity. Jerusalem: the Church of the Holy Sepulchre

In spite of much rebuilding by Justinian, who enclosed the whole of the east end with a trefoil sheath, the present structure still bears the impress of Constantine's handiwork (fig. 60). The church consisted of three main parts: the atrium or forecourt, the basilica and an octagonal chapel set up over the Cave itself, thus providing an early example of a church for congregational worship being combined with a martyr-shrine or its equivalent.

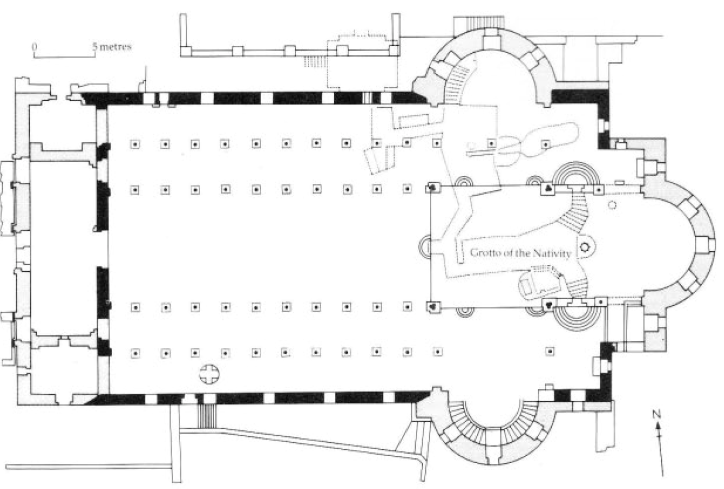

60. Bethlehem, Church of the Nativity: ground-plan

The atrium, some 27 metres wide, was enclosed by a covered colonnade which developed, on the east side, into a portico marking the entrance doors. The basilica, conventional in design, was divided by rows of columns into five aisles, the central aisle being about double the width of the others. The original foundation of large limestone blocks has been discovered beneath the floor of the present church, as have considerable portions of the mosaic floor, its richly patterned borders contrasting with the simple white mosaic of the atrium. Argument persists concerning the style and age of the columns. They have been claimed as part of Constantine's church but assigned by other archaeologists to the sixth-century restoration: possibly the answer is that they are original columns used a second time and increased in number by copies.

From the centre of the nave, at its eastern end, a flight of steps led up to the octagonal shrine, where again the scene was brightened by a carpet of mosaic on the floor. And, since devout pilgrims would wish to look into the Cave, a circular shaft, about twelve feet across, was driven down from the level of the floor and surrounded by a plain stone kerb with steps arranged on an octagonal plan. A metal screen seems to have been provided together with colourful hangings while, above, a hole was pierced in the roof to admit rays of light illuminating the birthplace of the Son of Righteousness.

Tinged as it may have been with political prudence and a streak of vanity, Constantine's fervent piety drove him restlessly on, at the end of his reign, to mark three other sacred places of Palestine with appropriate shrines.

One of these was the ancient sanctuary of Mamre, where the angels met Abraham with the encouraging message that 'Abraham shall surely become a great and mighty nation'. A yearly fair was held at Mamre when Jews, Arabs and Christians carried out an elaborate ritual which included the lighting of lamps and the offering of libations. Constantine was shocked by such irregular superstition and suppressed it, establishing instead a church 'worthy of the antiquity and holiness of the place'.

This church, so far as it can be traced now, was quite small, having only three columns on each side of the nave with an apse at the end, enclosed within the rectangle of the building. At the west side, a long porch (narthex) was continued to form additional rooms on both sides, while another set of side chambers, apparently used as sacristies or for administrative purposes, projected at the east end. The whole was enclosed within a precinct containing the oak tree near which Abraham was sitting when he received the divine message.

With this sanctuary at Mamre may be compared the Church of the Loaves and Fishes discovered at El Tabgha by the shores of Lake Gennesareth in 1932. This was a squat basilica of standard type, with courtyard and narthex. A mosaic of high quality, found within the curve of the apse, shows a basket flanked by two fishes and containing some loaves marked with crosses, thus linking the miracle with the Eucharist, while in front, at the centre of the apse, lies the stone referred to by the pilgrim Aetheria: 'the stone upon which the Lord laid the bread has been turned into an altar.

Visitors take away chips of this stone, since it heals all ills. Aetheria wrote in 385 ad while church and mosaic belong to a period some fifty years later, but underneath remains have been found of a diminutive, earlier church, just under 17 metres long, which must have been the one which Aetheria knew and goes back to a time not much after Constantine’s death, even if it is not to be numbered among his foundations.

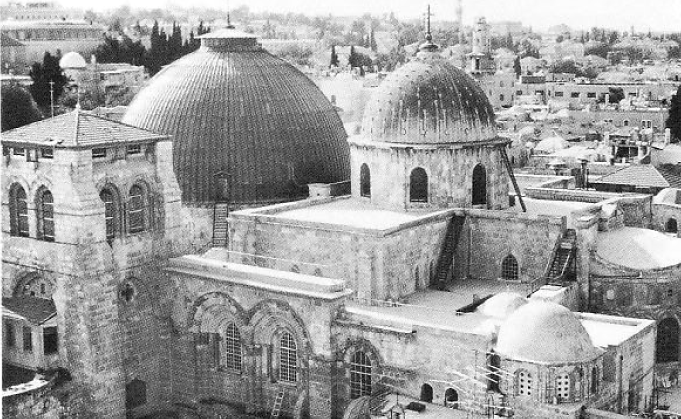

Constantine's Church of the Holy Sepulchre, including both the tomb of Christ and the rock of Calvary, was a larger and more ambitious structure than that at Mamre, but gained its distinction less from its size than as the result of a stately sequence of courts and buildings leading from one to the other. Everything has been so completely remodelled in the course of time that the description given by Eusebius in his Life of Constantine offers a clearer picture than is yielded by any results of excavation. Standing close to the centre of Jerusalem, it supplanted a temple of Aphrodite which the emperor caused to be demolished, revealing the cave and the rock which the church was then built to enshrine.

The impressive entrance (fig. 61) — 'very attractively designed', as Eusebius remarks—led from the main shopping street of Jerusalem into an open courtyard. The courtyard, with its rectangle of columns and fountain in the middle, gave access to the facade of the church where, to borrow Eusebius's words again, 'three doorways, well arranged, admitted the crowd of those who came in from outside.' No measurements are recorded but the church was clearly a wide building, and distinctly stumpy. What amazed all beholders was the brilliance of the decoration.

61. Jerusalem: the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in its relation to the city today

Constantine, in a letter to the bishop of Jerusalem, had instructed him to ensure that this building should be 'better and more beautiful than any in the world', and insisted that there should be no lack of marble or precious metals. And so it worked out. The two rows of columns on each side separating nave from aisles, and the galleries set above the aisles, may have presented an unremarkable design but the inner surface of the building was hidden beneath layers of polychrome marble: the ceiling was decorated with carved panels which, resembling a great sea, surged continuously over the whole basilica and the glistening gold with which the ceiling was covered made the whole shrine sparkle with a thousand reflected lights.

Such was the impression of Eusebius, who added that the exterior had by no means been neglected:

The outer aspect of the walls, bright with polished stone admirably laid presented an unusual beauty in no way inferior to that of marble. As regards the roof, its outer surface was covered over with lead, a sure protection against the winter rains.

At its west end, the basilica was completed with what Eusebius calls the 'hemisphere', decorated with twelve columns corresponding to the number of the apostles. Large silver bowls, presented by Constantine, capped the columns, which were enclosed at roof height by some kind of dome. This seems an elaborate structure if it was designed merely as an apse in which to seat the bishop and other clergy. Its use can only be guessed at; but a possible explanation is that it enshrined a relic of the True Cross. Another opinion is that Eusebius failed to get his facts right, and that the curving range of twelve columns extended from the basilica into the inner court to honour the relic of the Cross which the pilgrim Aetheria described as being in the open air. Still other critics interpret the 'hemisphere' as an early form of the rotunda encircling the Sepulchre.

Calvary, the traditional scene of the Crucifixion, was in the uncovered courtyard immediately to the west of the basilica. The rock itself, some four metres in height, had been chopped in forthright fashion to give it a more regular shape and to render it serviceable as a pedestal for the jewelled cross erected on top of it. The stately complex of buildings, well adapted for solemn, liturgical processions, extended still further west to include the circular, domed structure which sheltered the Sepulchre. Some of the lower courses of masonry here belong apparently to Constantine's own period, while the dome is illustrated by a little painting on the top of a seventh-century Palestinian reliquary now in the Vatican: it was made of stone, or just possibly wood, and had a range of semicircular windows round the base.

The edifice as a whole contained a wide passageway running all round the inside of the main wall. Next came a circular colonnade, leading up to the smaller columns of the gallery above, which served as a support for the dome. And last, exactly in the centre of the rotunda, was the rock cave which bore witness to Christ's victory over death. With a certain lack of historical sense this monument again had been modified from its original shape, in order to suit Constantine's architectural arrangement. The tomb was cut out in isolation from the surrounding rock and the approaches levelled in order to provide a smooth surface for the pavement of the rotunda. Columns, with metalwork grilles between them, were set round the grotto to protect it and to support a pointed canopy, while 'embellishment of every possible kind' conferred the splendour required by the fashion of the time.

Veneration was paid not only to the tomb itself but also to the stone which, as St Matthew records, served as a seal and was rolled away by the angel. This stone was held to offer a 'witness to the Resurrection', at some point it seems to have been broken in two, and one piece, enclosed within a metal sheath, used as an altar. The majestic combination of holy places on Golgotha so impressed the historians that they likened it to the New Jerusalem foretold by the Prophets and appearing in the visions of the Apocalypse where the Throne of God and of the Lamb is seen to supplant the Temple of the Ancient Law.

Date added: 2022-12-11; views: 2254;