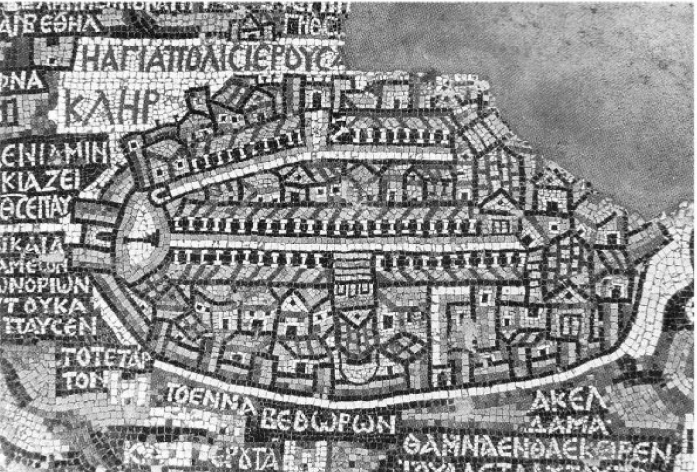

Madaba: the Mosaic Map of Jerusalem

Less than three hundred years after its construction this great shrine of the Anastasis, devised bv the emperor and attributed by tradition to an architect named Zenobius, had been destroyed by the Persian.

Subsequent rebuildings transformed the coherence of the earlier plan but some idea of what it looked like may be drawn not only from the rhetorical language of Eusebius but from two ancient illustrations. One is the fourth-century mosaic in the church of S. Pudenziana in Rome, where the Church of the Nativity appearing on the left side of the triumphant Christ is balanced by a second church, suggesting the rotunda and adjacent buildings of the Anastasis. The other is a mosaic of very different character, a map found on the site of a Christian church at Madaba, in Moabite territory east of the Dead Sea.

This map, now much damaged, dates from the middle of the sixth century and shows the land of Palestine in such fashion as to provide a commentary on events of the Old and New Testament. Various combinations of line and colour are used to indicate sea, mountain and plain, while a whimsical touch is given bv the fish in the rivers, a lion chasing a gazelle and two enormous ships, entirely out of scale, afloat on the Dead Sea. The smaller towns are marked conventionally, by a wall with two or three towers and the name inscribed above, sometimes with the addition at one side of a Scriptural text. The larger towns, however, are represented in an individual manner which could lay claim to realism. Thus Jericho is set in its circle of palm trees, while Lydda is shown with a colonnade surrounding a wide market-place with a splendid church at one end.

But the treatment of Jerusalem is on an altogether grander scale (fig. 62). The entrance by the northern, or Damascus, gateway stands out clearly on the plan, together with Hadrian's column in the open space nearby. Thereafter the central High Street with its arcaded shops strikes firmly through Cheese Market to the fortified Cate of Benjamin. Various buildings may be identified with reasonable assurance, but little attempt is made to maintain proportion. The chief emphasis is laid on the Church of the Anastasis, which, with only a slight deviation from exact geography, is placed precisely at the mid-point of the picture.

62. Madaba: the mosaic map of Jerusalem

A strain of symbolism is at work here. Some commentators held, with reference to the Psalmist's words ‘God is in the midst of her', that Jerusalem was the centre of the Universe and that the central fact of history, the death and resurrection of Christ, would naturally have occurred at the mid-point of Jerusalem. Such a place was, in any event, particularly appropriate for the tomb sanctuary of the Founder-Prince in his capital city of the New Israel. Something like a bird's- eye view is given of the church, and its various parts are clearly distinguished. The large courtyard leads from the market-place towards the three entrance doorways of the basilica, whose golden pediment and high-pitched red roof contrast, as architectural features, with the large golden apse representing the dome over the sacred spot.

The rotunda of the Anastasis, like that of S. Costanza in Rome, showed how the classic form of an imperial mausoleum could be drawn into the service of the Christian Church. Once the pattern had been laid down with such authority it was widely followed, and circular, or sometimes polygonal, buildings of this general type, which conveniently sheltered sacred remains or marked a hallowed site, became fairly widespread in Palestine and elsewhere. The church of St Carpus and St Papylus in Constantinople, which may date from as early as 400 ad, is sometimes instanced as a direct copy of the Anastasis. Certainly its ground-plan reproduces that of a domed hall surrounded by an ambulatory. But the vaulting is of brick rather than stone, and the ambulatory at one end finishes in a secondary apse which makes the building lop-sided.

Another set of Constantine's grandiose structures marking the holy places of Palestine was situated on the Mount of Olives and linked with the record of Christ's Ascension. But the remains that still exist are scanty and identification by no means easy amid the numerous churches and chapels of ancient foundation built on the mountain; a pilgrim named Theodosius calculated that there were twenty-four by the end of the fifth century. According to the contemporary evidence of Eusebius, the emperor's mother, St Helena, founded two churches there. One was set over the cave in which Christ gave final instructions to his followers: 'Go forth and make all nations my disciples', the other marked the spot which still bore the impress made by Christ's feet at the moment of the Ascension.

The Carmelites of Jerusalem, in the course of their recent excavations, have discovered traces of a large basilica very near to the highest point of the Mount of Olives. The masonry of this church, consisting of rough local stone cemented with lime mortar, points to the fourth century insofar as it indicates any clear date. Beneath the apse lies a grotto which was apparently connected by stairways with the aisles. It is therefore a reasonable, if not an entirely certain, conjecture that this is the Church of the Final Instruction where Christ 'initiated his disciples into secret mysteries'.

Some sixty metres away, exactly at the top of the mountain, fragments of walling have been disclosed which seem to fit accounts of the Chapel of the Ascension, founded by Helena. The structure follows, in general, a classical type of domed mausoleum, where the thick outer walls of an octagon, pierced by at least two entrance doorways, enclose a broad ambulatory flanked on the inside by a circle of columns. At the central point within the circle lay the venerated spot, a patch of earth left untouched by the surrounding pavement, which was here raised up sufficiently to allow pilgrims to see without causing damage.

Date added: 2022-12-11; views: 1161;