The Basilica – the Achievement of Constantine

To the impulses of Christian piety were added the solid encouragements of imperial favour. Constantine cast himself in the role of reconciling a divided world through the two instruments of an enlightened public policy and the unifying force of a common faith.

His triumphal arch in Rome showed him crushing the forces of Maxentius in the fashion of Moses delivered from his adversaries at the Red Sea, while the motto inscribed on the arch declared him to be acting 'through divine inspiration and with the greatest breadth of sympathy'. While refusing to alienate paganism he sought to ensure the support of Christians by furthering the spread of their doctrines so that, as Eusebius enthusiastically put it:

We saw every place which, but a little while ago, had been laid in ruins by the evil deeds of the tyrants reviving as though from a long and deadly destruction, and temples once more rising from their foundations to a vast height and receiving a magnificence far greater than that of the buildings which had formerly been demolished.

Constantine extended his patronage widely, but the principal scenes of his activity were Rome, Constantinople and the holy places of Palestine. Unlike the medieval builders, with their desire to demonstrate their faith by vaults, windows and towers soaring heavenwards, Constantine remained content with the unobtrusive though effective forms of basilica-hall and martyr-shrine. The choice of materials might vary according to local custom, but lavish expenditure on decoration was expected in order to convey a sense of unearthly splendour and, incidentally, to demonstrate the emperor's 'generosity and piety’.

One class of Constantine's churches, however, seems to have lacked any great elaboration because the buildings were closely packed with tombs and funeral monuments of every type: such were the large basilicas constructed over a martyr's underground grave. Like the basilica maior of St Laurence, the church recently mapped out beneath the Baroque trappings of S. Sebastiano at Rome seems to have consisted of a large nave with clerestory windows looking out over much lower aisles, the apse being enclosed by an ambulatory, or passageway, large enough to permit orderly movement of the devout sightseers.

The church of S. Sebastiano is not attributed to Constantine in the Liber Pontificalis. This, the official chronicle of the Roman bishops, assigns to his enterprise seven churches, three outside the walls and four within, which, though serving adequately as general meeting-places for worship, owed their form and individual character to the presence of a revered tomb. Just as, in Palestine, the exact points traditionally linked with the Nativity and the Holy Sepulchre dictated the shape of Constantine's structures, so, in Rome, convenience was sacrificed in order to make the martyr's grave a readily accessible focus of honour. Nowhere is this zeal to derive the utmost benefit from a sacred spot more amply demonstrated than in the case of St Peter's.

There it was not a matter of using an obvious and ready site but of removing a number of tombs and then constructing an enormous platform cut into the hillside at one end and, at the other, raised on massive foundations to a height of nine or ten metres. The whole affair represents a notable feat of engineering, and indeed Constantine's church lasted more or less unchanged throughout the Middle Ages. It was then judged insecure and replaced during the sixteenth century by the vast building set up to the designs of Bramante and the other Renaissance architects who succeeded him. Fairly extensive traces of Constantine's church have, however, been revealed by excavations which confirm three other types of evidence. In the first place there are several written accounts, beginning with a notice in the Liber Pontificalis.

This begins by making the rhetorical and not very exact claim that Constantine, urged on by Bishop Silvester, built the basilica of St Peter and enclosed the Apostle's coffin within layers of solid bronze. More valuable is the information which follows: 'Above the grave Constantine set columns of porphyry as an adornment together with other spiral columns which he had brought from Greece.' The barley-sugar columns, carved in spiral channels with alternating bands of vine ornament, exist to this day though moved from their original site. Their curious shape, and a medieval tradition that they had once formed part of Solomon's Temple, appealed to Raphael and, perhaps through the influence of his cartoons, they were widely copied in such unlikely places as the University Church, Oxford.

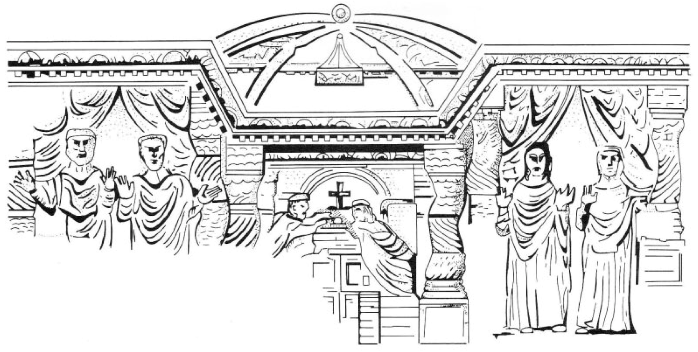

Another piece of historical evidence is furnished by the fifth-century ivory casket found near Pola, in Dalmatia, and now in the museum there (fig. 56). One side of the casket is carved with a stiffly formal representation of the shrine at St Peter's. The barley sugar columns support a rather elaborate cornice beneath which stand male and female worshippers with raised hands or, since there are curtains drawn back behind them, figures of the faithful departed.

56. Pola, the Museum: ivory casket showing St Peter's, Rome

The cornice is recessed on each side of the shrine itself and supports the four ribs of a canopy from which hangs a circular lamp such as, in the Liber Pontifical is, receives mention as one of the gifts bestowed by the emperor. The shrine itself, protected by a low screen, is made to resemble a large cupboard with doors and surmounted by a cross, while two devotees crouch beside it.

The third piece of evidence is the drawings made by sixteenth-century artists shortly before Constantine's church was destroyed; attractive in themselves, they appear from the evidence of recent excavations to be accurate also. The church faced westwards and it was that end which Constantine finished during his lifetime, as a dedicatory inscription on the triumphal arch indicated, while the rest of the building seems to have been completed slowly, over a period of about thirty years, but in accordance with the original design. The visitor approached it from the east by means of a flight of steps leading into a large, enclosed courtyard with an elaborate fountain in the shape of a bronze pine-cone. He then saw, ahead of him, a plain portico set in front of the five doorways leading into the church itself. This, following the precedent of St John Lateran, consisted, for the greater part of its length, of a high nave with double aisle on each side (fig. 57).

57. Rome, Old St Peter's: Ground-plan, c. 1820, based on the work of Tiberio Alfarano, De Basilicae Vaticanae structura

The large hall, colourful but bare, impressed the spectator with its forest of lofty columns dividing nave from aisles, as Gregory of Tours records:

St Peter the Apostle is buried in the temple which in ancient times used to be called Vaticanum: it has four rows of columns, marvellous to see and ninety-six in number. There are four more around the altar, making a hundred in all, besides those which support the canopy over the tomb.

The basilican part of the church seems to have served, like the nave of a medieval cathedral, as a meeting- place for all and sundry, beggars and pilgrims, the curious as well as the devout. It was used also as a place of burial.

Date added: 2022-12-11; views: 1130;