Cologne, St Gereon. Trier: the Basilica Today

The remarkable vigour and ingenuity which the emperor Diocletian passed on as an inheritance to his Christian successors is to be noted further north than Milan, in one or two of the great border towns of Germany. These, though serving from time to time as imperial residences, were in the first place military strongholds, with precise town plans and robust fortifications. But the arts of civilization, and architecture in particular, were not neglected. At Trier the imperial baths were constructed in the liveliest fashion with a number of projecting apses which make up a ‘symphony of cross-vaults, domes and half domes'.

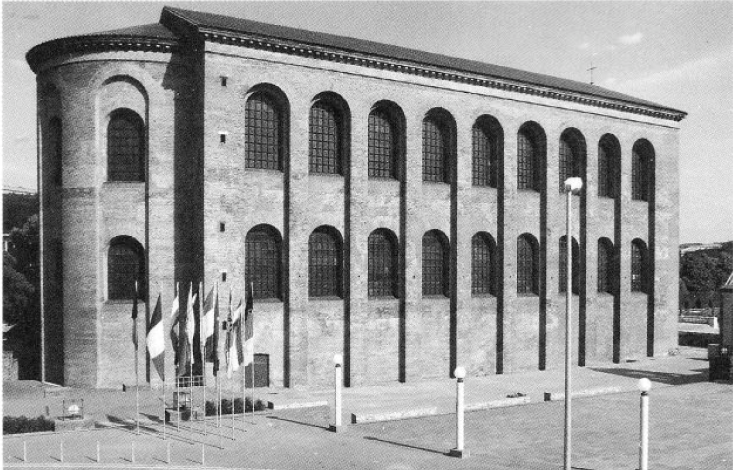

Nearby, in a contrasting style, plain, rectangular and flat-roofed, rose the basilica (fig. 72)—the town hall which served as law court and market. Moreover the cathedral, though devastated by the Franks and largely rebuilt in the Romanesque style, incorporates a substantial amount of the fourth-century structure. It seems that Constantine handed over the remains of an imperial palace, from which fragments of a richly decorated ceiling still survive, as part of the site on which to build a double church. Both naves are long and narrow, the northern being appreciably the larger, while between the two ran a substantial passageway containing a baptistery.

72. Trier: the basilica today

The southern building is completely superseded by the present Liebfrauenkirche, but portions of the earliest walling in the cathedral indicate a structure of red sandstone with binding courses of brick or tile and a plain, plastered exterior. The east end, as remodelled fifty years later by the emperor Gratian, formed a tall, square block. Four vast granite pillars, connected by arches, upheld the central tower, while other compartments were ranged around with complete exactness. At each side of the square in the middle was set a rectangle, furnished with two rows of large roundheaded windows and a sloping roof lower than the height of the square turrets which marked the four corners.

The external appearance, severe but in no way lumpy, must have resembled that of S. Lorenzo at Milan, and hints at a close connection, in styles of building and architecture, between the two cities. But the bold design, whatever its artistic merit, was chosen for practical ends. If the discovery of an arcaded recess sunk into the floor beneath the tower is anything to go by, this part of the building served the purpose of a martyr-shrine or perhaps a relic-shrine containing a portion of the True Cross discovered by the empress Helena.

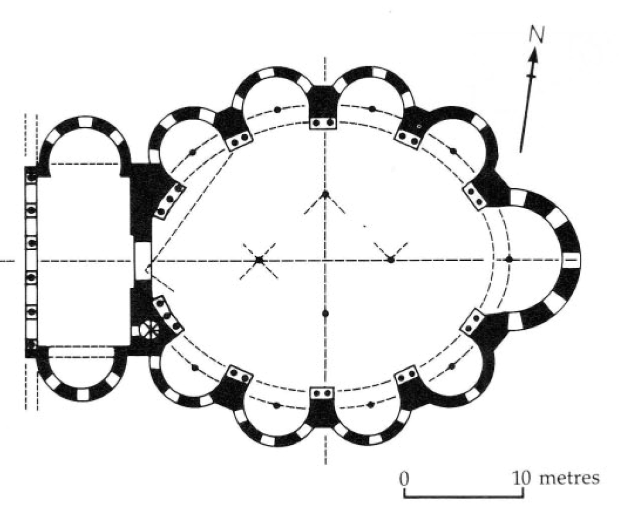

Another outpost city in which such emperors as Constantine and Valentinian I took a keen interest was Cologne. It is claimed on behalf of several of the churches here that they stand on fourth-century sites, but the only one which retains any part of its original form is St Gereon. This structure, now sandwiched between a long Romanesque choir and a square vestibule, is oval in shape, marked out by ten heavy piers supporting clerestory and roof. Between the piers the wall is recessed to form a series of vaulted semicircular niches (fig. 73).

73. Cologne, St Gereon: ground-plan of the fourth-century martyrium

The larger ones, which used to mark the entrances respectively to a western narthex and the eastern apse, have been much modified, but the other sides match each other precisely with their four niches of identical size. The church presumably derived its unusual shape from the pattern of a pagan temple or imperial audience hall; it has been compared with the building known as the Temple of Minerva Medica in the Esquiline district of Rome.

Date added: 2022-12-11; views: 781;