S. Lorenzo: View and Plan

The most important city in Italy after Rome itself was Milan, which became the centre of government in the West when, at the end of the third century ad, Maximian divided the imperial power with Diocletian.

Maximian, and others after him, saw to it that Milan was handsomely equipped with public buildings of every description including a theatre, baths, a Circus—'the people's joy'—and a number of temples. Milan had its honoured list of martyrs, Valeria, Victor and the rest, and after the year 313, when the Edict of Milan 'granted both to the Christians and to all the free choice of following whatever form of worship they pleased' numerous shrines were set up throughout the city. In 374 Ambrose became bishop, and his combination of spiritual authority and political shrewdness made Milan for a time the most obvious source of ecclesiastical power in the West; thus the fourth century, for the Christians of Milan, was a period of enthusiastic vigour and enterprise.

Five churches still exist which date from this epoch and, though much altered or even fragmentary, they show, amid considerable variety, characteristic features in common. The buildings are notable externally for a stern solid grandeur. This is evident in the best known of them, the church of S. Lorenzo (fig. 70), more easily visible now that a huddle of miscellaneous buildings has been cleared away from the Piazza Vetra.

70. Milan, S. Lorenzo: view from the south-east, showing the chapel of S. Aquilino

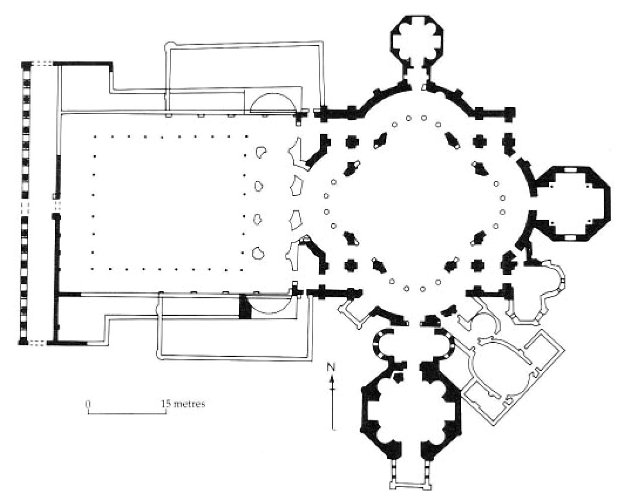

Four squared and lofty towers rise at the corners of the church, flanking what is now a sixteenth-century cupola but which seems originally to have been a dome constructed in stone or timber. Beneath this, the square hall was modified at each side by a shallow apse, its shape repeated in the lines of the ambulatory which surrounded it (fig 71). This attractive design, commonly known as the 'double shell', was copied from baths or other palace buildings and, like so much else, christianized and used experimentally for church purposes in the fourth century. At S. Lorenzo it is modified, apart from a cluster of later additions to the south-east, by three ancient chapels.

71. Milan, S. Lorenzo: ground-plan

The largest of these, dedicated to St Aquilinus, is known also as the Queen's Chapel because of a tradition that the empress Galla Placidia wished to be buried there. It is shaped as an octagon with niches in the walls, and retains decoration in marble and mosaic such as originally characterized the whole structure, sombre outside but bright and lively within. The church was approached from the west by way of a large courtyard in front of which stand sixteen marble columns originally used in a pagan temple. S. Lorenzo is sometimes described as the Arian cathedral, but perhaps the most that can be said is that it may well have been founded by Auxentius, an astute native of Asia Minor who preceded Ambrose as bishop of Milan. Lying rather apart from the main part of the city it could then have preserved Eastern and Arian rituals at a time when the rest of Milan was becoming predominantly Catholic.

Two other fourth-century churches exist at Milan in the sense that large sections of the original walling have been incorporated in a structure which, though modified by later developments, is substantially of the Romanesque or Lombardic period. St Ambrose established his Church of the Apostles in 382 ad on a site hallowed by the presence of an early Christian burial-ground, but it was renamed S. Nazaro when Ambrose placed there the bodies of the local saints Nazarius and Cclsus. The form of the building, probably suggested by Constantine's Church of the Holy Apostles at Constantinople, is that of a tall cross. The nave, some 60 metres long, ran without interruption to the apse at the east end; the transepts, forming the side arms of the cross, were connected to the nave by an arcade of three arches, so that those who crowded into the transepts on occasions of high festival could have a good view of the altar, set as it was at the central point of the cross with the sacred relics deposited beneath it.

The church of S. Simpliciano has a somewhat similar history. Here again the site is that of a primitive Christian cemetery where an unpretentious meetinghouse was transformed by the vigour of St Ambrose into a noble cross-shaped building. Originally entitled St Mary and all the Virgins, the church later took the name of Ambrose's successor as bishop of Milan, St Simplicianus, who acquired a number of martyr relics for it. The nave, ending in a spacious apse, was roughly the same length as S. Nazaro but appreciably wider, 22 metres as compared with 14.5. Of this first building some lofty external walls, made of well-laid brickwork, still remain.

Milan Cathedral, the construction of which began in 1386 ad, is well known as a particularly ornate example of the late Gothic style but the construction of airraid shelters during the last war led to the discovery beneath the Piazza del Duomo of the original cathedral, built towards the end of the fourth century and remodelled about a hundred years later. The indications are that the building was shaped as a rectangle ending in a shallow apse.

The nave was separated from the aisles by columns, a double row on each side running as far as the chancel and then continuing rather irregularly across the two chancel wings which extend to the springing of the apse. These wings may have been no more than sacristies or storerooms but they suggest the tripartite transept of S. Pietro in Vincoli at Rome and similar types of transept which established themselves in favour throughout the Aegean region during the fifth century. Another feature, more characteristic of the Aegean than of the West, which the remnants of Milan's first cathedral indicate, is the arrangement of the chancel. The usual practice was for the clergy to occupy seats around the walls of the bema or 'tribunal' —that is to say the apse alone or the apse together with part of the transepts.

In order to provide added dignity for the bema and for the altar which was often placed there, the floor might be raised and, whether raised or not, was equipped with screen partitions 'delicately wrought with the craftsman's utmost skill', so that 'the multitude might not tread in the midst of the holy of holies'. With a view to bringing the clergy more closely into relationship with the populace for purposes of either Communion or sermon-preaching, a raised pathway, known as the solea, was sometimes extended from the chancel screen into the nave. This Eastern device is repeated at Milan, where portions of the solea jut out into the nave for a distance of 12.5 metres.

What may therefore be said in summary is that recent discoveries show the citizens of Milan, in the time of St Ambrose, to have displayed both energy and skill in church-building, receiving and adapting ideas which had developed in Constantinople and possibly initiating certain elements of architectural style which others saw fit to copy later on.

The church of the martyrs Gervasius and Protasius, built by St Ambrose above the cemetery where the two saints were buried, and later named S. Ambrogio, is rightly described by the guidebooks as 'fount and symbol of the religious impulses of Milan', but, though restored with accuracy and good taste after damage suffered during the Second World War, has little to show dating back further than the ninth century. Excavation has served merely to indicate an original building with long nave and aisles terminating in a semicircular apse, a straightforward basilican plan that was widely copied elsewhere in northern Italy.

The attached chapel of St Victor is, however, of very early date and shows the characteristics of fourth- century workmanship—simple, severe lines with a rhythmical arrangement of round-headed windows designed to provide ample light subtly changing with the time of day. The roof of the central portion is a cupola made up of pottery tubes arranged in rings and perhaps originally contained within a protective drum, while the lower surface of the cupola shone with such a splendour of golden mosaic that the chapel was nicknamed St Victor of the Golden Heaven.

Date added: 2022-12-11; views: 931;