Santa Maria Maggiore, S. Stefano Rotondo, S. Angelo: Interior

The slender elegance of S. Sabina admits of no rival in Rome for beauty of form, but the same style, harmonious and rhythmical yet perfectly adapted to the purposes of congregational worship, is used to excellent effect in the majestic church of S. Maria Maggiore (fig. 67). Here, however, the fifth-century simplicity is much modified by a variety of later additions. It seems that there had been an earlier church on the site, adapted from a civil basilica, but this was completely destroyed by Pope Sixtus III and replaced by a more ambitious structure in the neo-classical fashion of the times. Besides being an enthusiastic patron of the arts, Sixtus was active in his opposition to the Nestorians, who stressed the humanity of Christ at the expense of his divinity, and a desire to emphasize the newly-propounded doctrine of 'Mary, the Mother of God' was no doubt one of the influences which drove him on to erect so grandiose a building in honour of the Virgin.

67. Rome, S. Maria Maggiore: interior

The nave, 88 metres long and 33 metres high, is separated from the aisles by forty marble columns, topped by Ionic capitals, that were originally made for a temple of Juno Lucina. The capitals have superimposed upon them not the high flung arches of S. Sabina but the firm horizontal line of an architrave, a stately and somewhat heavier design which allows ample space for framed panels of mosaic. Twenty-seven of these panels out of the original forty-four remain more or less intact and display a lively interest in the historical details of the Old Testament, from Abraham to Joshua, without much attempt to derive symbolic meaning or doctrinal lessons from them.

As early drawings of the church indicate, the mosaic panels were formerly contained within plaster frames with barley-sugar columns at each side and a low pediment above, while the tall round-headed windows of the clerestory were set higher still. There were, however, irregularities and variations in this pattern, and the whole arrangement was simplified in the interests of an ordered uniformity during the eighteenth century. Precious as these nave mosaics are, they must always have played, as they do now, a relatively small part in the decorative scheme of the vast church. The compositions tend to be crowded and, as in the case of medieval stained glass, it is often difficult from ground level to make out the events represented. A general effect of brilliance would, however, have been secured by the mosaics as the light from the windows on the opposite side of the nave fell upon them.

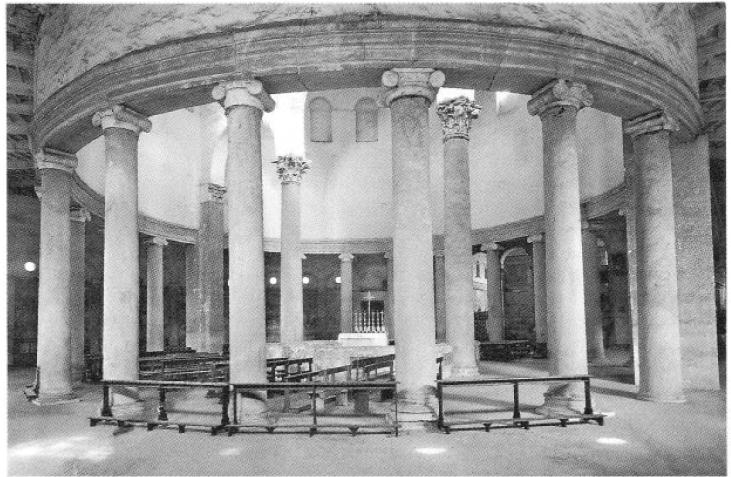

A similar respect for tradition and balanced good taste appears in a building of very different type, somewhat later in date but archaic in feeling: the church of S. Stefano Rotondo (fig. 68). As its name implies, this is a circular structure, formed more on the pattern of a martyr-shrine than of a congregational meeting hall, and perhaps intended by its founder, Pope Simplicius (46&-83 ad), to house relics of St Stephen. The building consists of a large drum set upon a ring of twenty-two granite columns with Ionic capitals of white marble.

68. Rome, S. Stefano Rotondo: interior

The columns support an architrave on which rests the dome pierced by twenty- two windows, all but eight now blocked up. This round nave is encircled by the ring of the broad aisle, the outer side of which is marked out by a second series of columns, smaller than those of the nave and topped by arches instead of an architrave. The arches formerly opened onto yet another ring, now destroyed, which consisted of a perimeter wall joining the ends of four rectangular chapels. These, projecting from the main part of the building, suggest a cross superimposed on the circle and witness to the influence of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre at Jerusalem. Between the chapels there once ran little gardens open to the sky, affording clear light in effective contrast with the comparative darkness of the chapels.

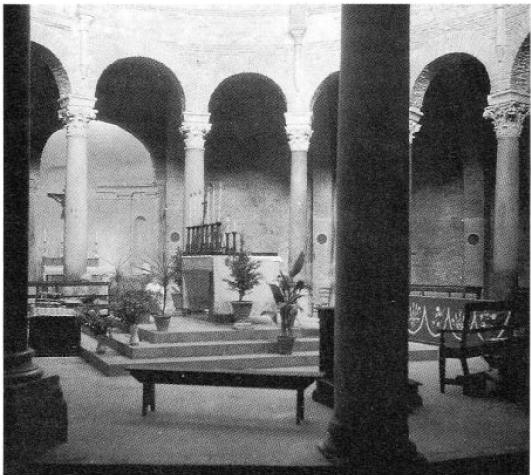

In the Western Empire there were few imitations of this type of building where the tradition of the mausoleum is boldly taken over as the form of a commemorative church. The best example is S. Angelo at Perugia (fig. 69), half a century later than S. Stefano.

69. Perugia, S. Angelo: interior

Here a wide ambulatory with an inner circle of sixteen columns supports the central drum, while four chapels, three square and one shaped as a horseshoe, extend outwards from the ambulatory along the lines of a cross. As at S. Stefano, Asiatic influences have been adapted to the Latin idiom.

Date added: 2022-12-11; views: 1078;