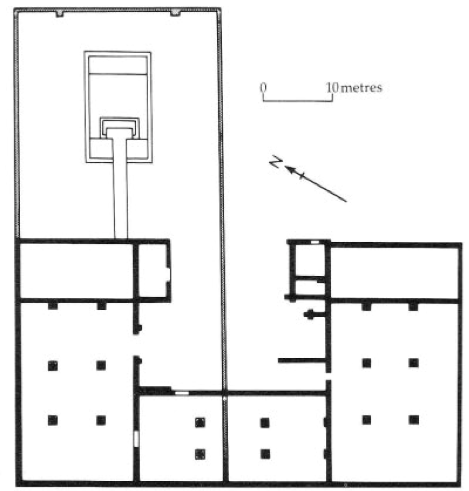

Aquileia: Plan of the Cathedral about 400 ad

The city of Aquileia, seven miles from the head of the Adriatic, grew up to become so powerful a military and commercial centre that it was known as a second Rome; and to Aquileia's rich store of civic halls and private houses Bishop Theodore added a group of ecclesiastical buildings designed with great splendour. The raids of Attila in 452, followed by the Lombard invasions, so devastated the city that it could be referred to as 'a beggar's hovel'. And, though in the Middle Ages life returned to Aquileia, which once again became a bishop's see, the works of the early Christian period have only lately been recovered, in a very fragmentary state, as the result of excavations.

The present cathedral (fig. 74), consecrated in 1031, preserves the basilican form but with sanctuary and apse raised to an unusual height. A large area of the floor is covered by a pattern of mosaic which, as an inscription shows, originally formed part of Theodore's church and is therefore to be dated about 315 ad. The cathedral seems to have grown up in clearly marked stages. The first building on the site was a Roman villa, datable to about 20 ad, from which there remain some portions of tessellated pavement and two walls of enclosure. In the precincts of this villa a fair-sized rectangular building was constructed towards the end of the third century as a hall of assembly for the local Christians.

74. Aquileia: plan of the cathedral about 400 ad, showing the two parallel halls. A few subsidiary buildings have been omitted

Not long afterwards Bishop Theodore amplified the original structure. The bishop's throne, together with the clergy bench, was placed at the east end, while a substantial screen separated altar and clergy from the pressures of the populace. Theodore then connected this building, by means of a covered vestibule, with another hall further south. The two halls were of the same length, 36 metres, and divided by six columns into nave and aisles. The south hall appears to have been designed as a school of instruction for catechumens but, if so, the arrangement did not last very long; the indications of an altar, clergy seats and so forth, together with the splendid decoration, point to its use as one of a pair of twin churches.

The richness and variety of the mosaic floor in the southern hall reveal it as a wholly exceptional work for its period. Swirling bands of acanthus leaves divide the mosaic into three zones, each again separated into three compartments; the scheme is completed with a wide band of decoration that once stretched across the entire width of the hall at the east end. In this mosaic, animals, birds and fishes of many kinds are shown with the affectionate realism which allowed even the most austere of the early Fathers to value 'a single tiny flower from the hedgerow, a single shellfish from the sea, a single fluttering wing of the moorfowl'. Sometimes the creatures are intended to point moral lessons.

The cock, bird of the dawn, fighting the grotesque tortoise, recalls the struggle between Christian enlightenment and heathen, or perhaps heretical, perversity, while the fish trapped in a vast net worked from a boat by graceful cupids call to mind the task laid upon all heavenly influences to gather the elect into the Church's net through the waters of baptism. Elsewhere round frames enclose portrait- busts of donors, more of them women than men, with whose generous support Theodore was enabled to build. Some of the roundels contain not a human portrait but a fish, while the space nearby is taken up by octagons, each displaying a bird—a peacock, perhaps, or a pheasant—perched on a flowering branch in Paradise. Similar birds, on a somewhat larger scale, are interposed between scenes referring to the Eucharist, the 'medicine of immortality'.

Here youths and maidens hold a basket of loaves or grapes or flowers, while, in a large square panel which dominates the whole composition, a dark-robed angel, clasping the wreath and palm-branch which denote victorious perseverance, stands behind the heaped-up loaves and the wine-jar In entire harmony with such emblematic pictures, the Biblical motifs chosen for illustration are the Good Shepherd and three episodes from the life of Jonah, who is also shown as an Orans clothed in the deacon's dalmatic. Framed in the mosaic just at this point is a dedicatory inscription in honour of Theodore who 'built and dedicated the church with splendour'.

Aquileia was the scene of the great Church Council of 381 ad, assembled in a vain attempt to repress the Arian heresy, and it appears that, shortly afterwards, Theodore's northern church was overhauled and enlarged with the addition of new columns, to become a wide nave with narrow aisles though retaining the earlier fashion of a plain, squared-off sanctuary. The outbuildings were extended at this time and the baptistery, with its marble-lined hexagonal font, set at a point where the water supply of the ancient villa could be utilized. The reasons for constructing double churches, a fashion favoured in the North Adriatic region as examples at Parenzo and Trieste show, need not always be precisely the same. A desire for grandeur, the manifold requirements of worship, and administrative convenience could all exert their influence in varying degree.

The Roman colony of Julia Concordia, 49 kilometres west of Aquileia, presents a cluster of Christian buildings designed to protect the city's burial-places and to ensure that the rites of commemoration were suitably observed. The most substantial of these structures began as a trefoil chapel, similar in style to those of St Sixtus and St Soter in the Cemetery of Callistus in Rome or the example at Damous el Karita, near Carthage. Originally this fourth-century 'trichora' consisted of three apses, circular within and roughly polygonal outside, with an open courtyard on the fourth side where the faithful might gather for services. The courtyard was then turned into a rectangular room, giving greater privacy and protection, by prolonging the side walls a little way and closing the gap.

After about a century this trefoil shrine was extended to become the cemetery church, enough of which remains to indicate its dimensions. It was a small basilica, 17 metres long by 10 wide, and divided by columns into a nave 4.5 metres across and two aisles rather more than half that width. The trefoil was incorporated to form the sanctuary and the eastern apse was therefore equipped with a bench for the clergy and, in the centre, a block of masonry to support the bishop's throne. At the opposite end of the building came the narthex, of the customary rectangular pattern and containing a handsome sarcophagus set in the place of honour beneath a canopy supported by columns.

The inscription runs: 'The holy priest Maurentius lies in his own burial- place at the threshold of the Church of the Apostles'. Beyond the narthex was a cloister, with fountain of the type which Paulinus of Nola described as 'washing with a serviceable stream the hands of those who enter'. There were also sockets, apparently for screens to prevent undue jostling at the entrance, while, at the side, rows of sarcophagi were neatly arranged in parallel lines.

Close to the original shrine at Concordia, and approached by a doorway from it, are two burial precincts of a type hitherto found nowhere else. Each consists of a line of three little rectangular cells, open in front and bounded by a wall on the other sides. On the inmost wall of the cells three niches are hollowed out, as for the reception of three coffins, but almost the whole of the middle cell of the eastern oratory is taken up with one splendid sarcophagus, carved on the front and right side with palms, vines and crosses, and inserted into the wall. An inscription tells the story: ‘Faustiniana, nobly born and servant of Christ, in her lifetime entrusted herself and her burial-place to the tabernacle of Christ and shrine of the saints.' Here 'tabernacle' means the chapel where the eucharisti liturgy could be celebrated, while the reference to the saints is explained by two recesses, intended to contain relics, at the foot of the altar which, as the postholes show, was placed in front of Faustiniana's tomb.

Generally comparable to Aquileia is a group of churches recently disclosed by excavation in the Austrian Tyrol. These date from the fourth or early fifth century and reflect an uncomplicated 'basilican' style. At Lorch the structure takes the form of a simple rectangular hall, divided in two by a cross-wall. Towards the east end, behind the altar and its associated recess for the storage of martyr-relics, there is a free-standing semicircular bench, a synthronon, for the clergy; attached to the north side of this chancel lay a sacristy. The church at Aguntum, though larger and slimmer, offers a closely similar pattern, but more imposing are the remains of the hillside fortress- church of Lavant.83 Here, behind the clergy bench, occurs a large rectangular compartment, also containing a horseshoe bench and explained either as a private chapel for the clergy or as a baptistery.

Notes: 1. Mentioned in Nehemiah 8.3.

2. Josephus, Jewish War vii.5.5.

3. Exodus 25.31.

4. G. F. Moore, Judaism (Cambridge, 1946) i.546.

5. Epistle of Barnabas 7, in The Apostolic Fathers (Loeb), i.364.

6. Ps. Clement, Recognitions 10.71, PG 1.1453. Revised text by B. Rehm in GCS.

7. Ecclesiastical History 8.1.

8. Against the Christians, fragment 76. See J. Bidez, Vie de Porphyre (Gand, 1913).

9. The term 'edict' is normally used; in fact it was a 'rescript' sent to an individual governor.

10. Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 10.5.

11. Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 10.39.

12. De Architectura v. 1.6, ed. F. Granger (Loeb), i.258.

13. The Antiquities of the Christian Church, viii.i (London, 1726).

14. Liber Pontißcalis, ed. Duchesne, i.153.

15. Full discussion by J. B. Ward-Perkins, 'Constantine and the Christian basilica', Papers of the British School at Rome XXII (1954).

16. Ignatius, To the Ephesians 20.

17. Apostolic Constitutions 8.42, PG 1. Later edition by F. X. Funk (Paderborn, 1905). English translation by J. Donaldson (London, 1870).

Date added: 2022-12-11; views: 1042;