The history of the Battle of Chaeronea

In August 338, the classical Greek world ended on the battlefield, near the small city of Chaeronea outside Thebes. Philip II, king of Macedon, defeated a Greek army composed of hoplites from Athens, Thebes, Corinth, Megara, Achaea, Chal- cis, Epidaurus, and Troezen. The Athenians under Demosthenes broke its treaty with Philip, who now moved south into Boeotia to confront the alliance.

Philip had been given command of the Amphitryonic Council to lead a sacred war against Amphissa, south of Delphi, for cultivating land sacred to Apollo; this gave him the religious right to enter Greece with his army, although he probably would have found some other pretext anyway. In November 339, he arrived at Phocis and successfully defeated the force protecting Amphissa, took over the town, expelled its citizens, and gave it to Delphi.

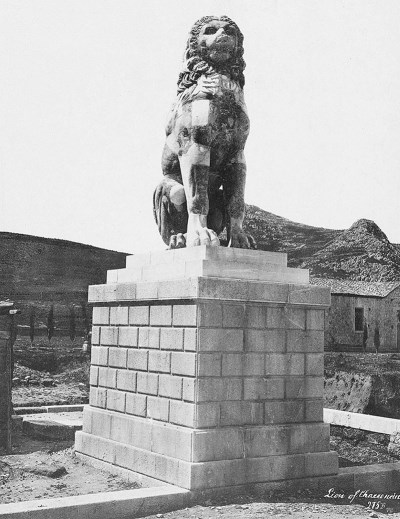

The Lion of Chaeronea, commemorating the battle won by Philip II of Macedon. (Rijksmuseum, Gift of J. C. P. Bierens de Haan)

With Philip’s arrival in Elatea, only three days by foot from Athens, the Athenians panicked at first, but they were calmed by Demosthenes, who suggested that they make an alliance with Thebes. Although Thebes was not yet at war, and Philip had asked them for permission to pass through their territory so he could march on Athens, the Thebans decided to ally with their traditional enemy, Athens, against Macedon.

There may have been several small battles or skirmishes during the winter, as suggested by Demosthenes. Finally, after diplomatic avenues were exhausted, Philip marched into Boeotia with his army against the allied forces at Chaeronea, which were blocking the road and holding the stronger position.

The Macedonian force, with its new phalanx-style infantry, numbered about 30,000 infantry and 2,000 cavalry. Philip commanded the right wing, while his eighteen-year-old son, Alexander, commanded the left. The forces were probably about the same magnitude, but the allied hoplites, mainly troops from Thebes and Athens, may have had a slight numerical advantage.

The Athenians were on the left wing, opposite Philip, while the Thebans were on the right, opposite Alexander, with the remaining allies in the center. The allied right line was next to the Kephisos River near Mount Aktion, while the left was on the foothills of Mount Thurion, which protected the allies on both flanks. In addition, since they occupied the high ground and had assembled their forces so that they slanted toward the northeast, the allies were ideally disposed on their two-and- a-half-mile front.

If Philip attacked the allied left wing, he would have to move uphill, while at the same time, the slanted allied front would have been able to attack Philip’s own left wing and potentially roll up the Macedonian line.

The battle appears to have been drawn out, perhaps to tire the inexperienced Athenians. Philip may have engaged the Athenians on their left wing for a while and then retreated in an organized manner to draw them away from their defensive positions.

Once the Athenians moved toward Philip and his right wing, the Macedonians were able to extend the Athenian line and then wheel about to counterattack. At this point, Alexander and his infantry on the left attacked the Theban Sacred Band, the elite infantry, and apparently punched a hole in the Greek line, probably where the Athenians had moved out to engage Philip.

Regardless of how the battle unfolded, the new Macedonian phalanx showed its superiority and flexibility over the Greek hoplite. The 300 men of the Sacred Band were wiped out, while over 1,000 Athenians were killed and more than 2,000 captured; the Thebans and other Greeks were likewise destroyed. A monument, the Lion of Chaeronea, marks the spot where members of the Sacred Band were buried.

The victory was complete for Philip and Macedon. Philip did not want to besiege cities or fight extensive campaigns since he needed them as his allies for his upcoming war against Persia. He then marched to Thebes, which surrendered, and he expelled the Theban leaders who had allied them with Athens; then he installed a Macedonian garrison for protection.

Philip disbanded the Boeotian Confederacy, the Theban alliance, and punished Thebes by reestablishing the cities of Plataea and Thespiae, which Thebes had destroyed earlier, in order to keep an eye on them. By contrast, he treated Athens leniently, allowing prisoners to be ransomed, probably in hopes of winning Athens to his side so he could use its navy against Persia. He also made peace with Corinth, which received a garrison.

Although Sparta did not help the allies, it was ravaged after refusing Philip’s negotiations; Philip, however, did not directly attack the city. Finally, in 337, he established the League of Corinth out of the members of the Greek cities (except Sparta) to declare war on Persia to help him in his conflict. The Battle of Chaeronea ended the Classical Age.

Date added: 2024-08-06; views: 483;