The history of the Minoan civilization

The history of the Minoan civilization is steeped in mythology and mystery. The traditional literary accounts from antiquity, which are few, note that the Minoans, descended from King Minos, created the Greek world’s first thalassocracy, or naval empire. This view occurred during the fifth century, when Athens had embarked upon creating its own naval empire and sought to show the connection with the past. Further legends had a great monster, the Minotaur, which lived in a labyrinth at one of the palaces at Cnossos.

Theseus, the son of the Athenian king Aegeus, with help from Ariadne, the daughter of king Minos, killed the Minotaur in the labyrinth. This mythological background was further enhanced by early archaeological excavations carried out by Sir Arthur Evans at the beginning of the twentieth century CE on Crete at Cnossos. He noticed that the palace was not enclosed by walls as other palaces on the Greek mainland were, and that it had an elaborate underground facility, a labyrinth with storage jars and rooms. In the absence of protective walls, Evans argued that Crete had a large fleet and its navy controlled the Aegean, which accounted for the absence of forts on Crete. The idea soon developed that the Minoans had a formable navy protecting Crete so that there was no need of forts, similar to those in Evans’s Britain of the late nineteenth century CE.

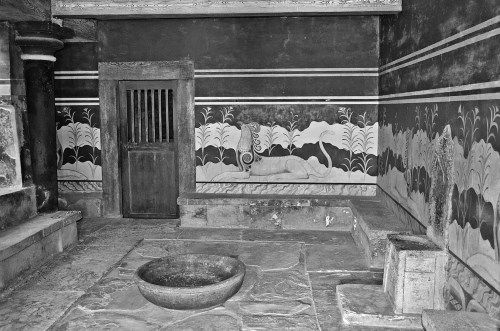

Minoan throne room at Cnossus, Crete

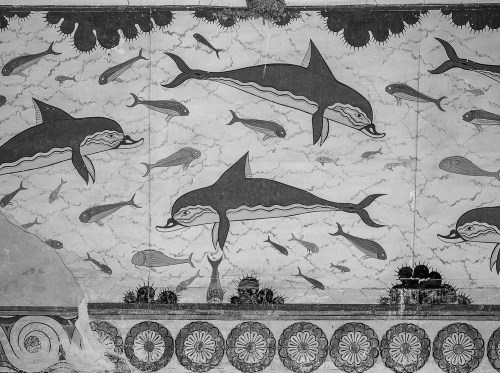

Dolphin fresco from Cnossus, Crete

Evans also dated the different periods of Minoan history through pottery, creating three main divisions, Early, Middle, and Late Minoan, which corresponded to Early, Middle, and Late Helladic on the mainland; each period was further subdivided into three eras. The archaeological evidence, especially pottery, help date and show the development of the Minoan culture. The first palaces on Crete were built around 2000, during the first stage of the Middle Minoan (2000-1900) period. Palaces were constructed at Cnossos, five miles from the sea on the north coast of Crete; at Mallia, thirty miles to its east on the coast; Phaestus, on the southern side of the mountains on the south of Crete overlooking the Mesara plain; and later at Zakro, on the far eastern coast.

These palaces show a break with the Neolithic culture of villages composed of huts and followed the Near East development of palaces at Mari or Ugarit. The development of the palaces probably indicated a move to centralized (most likely regional) government and writing.

The first type of writing on Crete was pictorial, similar to Egyptian hieroglyphics, and during the second period of the Middle Minoan (1900-1700), a syllabic script was developed at Phaestus, which Evans called Linear A. During this period, probably at its end, all the palaces were destroyed or heavily damaged, without traces of fire, probably indicating earthquakes, which are frequent on the island. These palaces were then rebuilt, but on a grander scale, in the next phase, the third era of the Middle Minoan (1700-1550), and existed from 1650-1450. They were in the same style and floor plan as earlier, but just larger.

The palaces had stone foundations, with the upper structures made of wood. The palaces differed slightly but had the same components, including a large central courtyard, which at Cnossos, Mallia, and Phaestus measured 170 feet by 80 feet. The courtyard was probably for public ceremonies, religious rites, spectacles, and festivals. Around this courtyard were separate blocks with different duties and functions. During this period, the palace at Cnossos was the largest, covering between three and five acres. The staterooms were located on the western side of the courtyard, with the more important rooms on the second floor, approached by a monumental staircase.

The first floor contained the ritual cult rooms. Farther west of the staterooms were the storage rooms, including the large pithoi used for storing oil and grain. On the east side of the courtyard were the royal apartments. The palaces were richly decorated with scenes of nature, and at Cnossos and other palaces, theaters were constructed that were capable of holding 400 people.

Other archaeological sites from Crete include the small village of Gournia, which had paved streets as well as homes built on the mountainside. A larger home existed farther up, which was laid out as a small palace and was called the squire’s house.” Also found there were carpenter’s tools and samples of fine pottery. The town was not important and was connected with agriculture, but it showed the diversity of wealth on the island at this time. Houses in larger cities had more elaborate construction and were multistoried.

The Cretan economy at this time was heavily dependent upon agricultural produce. In addition, forests covered the island, and the Cretans were known for trading in the wood industry, especially with Egypt, which was devoid of trees. Minoan pottery had been found throughout the Mediterranean, giving evidence of their extensive trade. The islands in the Aegean were probably the strongest trade partners with Crete, although there is no reason to believe that Crete dominated these islands, and many of them, especially the Cyclades, had their own cultures, which was independent at this same time. The only precisely known colony of Crete was in Cythera, off the southern shore of the Peloponnese, although others on Melos, Thera, and Ceos could have existed.

The Minoan religion seems to have been associated with natural sites such as groves and caves, where people brought their offerings. Temples do not seem to have existed at this time. It appears that palaces and some private homes had sanctuaries. The palaces were probably the major focus for the religious celebrations based on nature, with the most popular being the nature goddess guarded by lions. The goddess, with representation of snakes found in the palace of Cnossos, is probably the nature goddess who protected the palace.

In mythology, Athens was a tribute state that supplied seven boys and seven girls to Minos as offerings to the Minotaur. One of those, Theseus, the son of King Aegeus, killed the beast. It is here, in mythology, that the ideas of Crete need to be examined in light of the archaeological finds. The story of Theseus provides a good starting point. In mythology, Theseus and Heracles were contemporaries who lived two generations before the Trojan War, when the power of Cnossos had already been broken, as opposed to the Minoan myth where Theseus lived during the height of Cnossos. Further, Ariadne, the daughter of King Minos who helped Theseus in the myth, was a Cretan goddess, and Minos’s cruelty in feeding people to the Minotaur is not consistent with his other image in antiquity as a wise lawgiver.

The Minotaur is represented on some pieces of art, but no more than other demons introduced from Egypt, and it probably is an alteration of the traditional bull-leaping contests by young men and women depicted in Cretan art. The labyrinth is probably from the Carian word labrys (double-axe), a symbol found on Cretan walls, especially in one house called “the house of the double-axe,” with an intricate plan or maze. The myth of the Minotaur may have been a way to explain the elaborate palace and the motifs of the bull represented at Cnossos.

The Cretan palaces all disappeared in the middle of the fifteenth century, at their height, when everything but Cnossos dissolved into masses of rubble and ash. Originally, it was thought that Cnossos was destroyed at the same time, but Cnossos would only be destroyed after 1400. The countryside and small towns also showed destruction. What caused it? It was thought that the Mycenaeans had destroyed the palaces, but since Cnossos survived, it could not be due to them; also, it has since been discovered that when Cnossos fell, it already had been controlled by the mainland Greeks. Discovered in the palace ruins at Cnossos were baked clay tablets with a new form of writing, which Evans called Linear B. Later excavators found the same writing on tablets on the mainland, which led Michael Ventris, a classicist and linguist, to decipher them and label the language a preHomeric form of Greek.

The tablets further indicate that Cnossos was already under Mycenaean control at the time of its destruction. But why were the other palaces destroyed? One theory concerns the volcanic eruption at Thera (Santorini), which occurred around 1500. The tremendous eruption buried the island’s settlements, and Thera became three islands, with a crater in the middle filled with water, which could have caused a tsunami. Borings from the sea on the eastern side of the island show that deep deposits of ash were made both in the north and south, so it is possible that the ash covered extensive areas of Crete, especially in the east, making the land unproductive. The pottery, however, shows that the damage caused by the volcano occurred around 1500, while the pottery at the palaces occurred fifty years later, from 1450, meaning that their destruction was not contemporaneous with the eruption.

It is, therefore, probable that humans, possibly Cretan natives, Greeks, or other foreigners, destroyed the palaces. A social uprising is probably not the cause since minor towns were also destroyed and wealth was not concentrated in the hands of a few, which could have produced a strong social upheaval in that case. There is evidence from around the eastern Mediterranean of raiders attacking regions in the fifteenth century, but trade expanded in the east with Crete and does not seem to fit a pattern of plundering raids happening at the same time or immediately afterward. One idea that has been proposed has the Theran eruption of 1500 destroying the Minoan fleet, which allowed the Greeks to enter the island and destroy the other palaces in 1450 and then take over Cnossos before it was destroyed in 1400.

It is probable that the Greeks did indeed attack the island, but the idea of a Minoan navy being destroyed would not depend upon their success. If the Mino- ans did not have a navy, then the Greeks, probably from the Argolid or Mycenae, took over the island, destroying the rivals of Cnossos and concentrating power there. However, this explanation does not account for the destruction of Cnossos some years later. Evans believed that this was caused by an earthquake, but if that had occurred, then the palaces would have been rebuilt. Another idea was that the Mycenaeans on the mainland decided to eliminate a rival sect on Crete. The pottery evidence shows that the destruction took place a bit after 1400, but definitely before 1350, so any kind of link between the Minoan destruction and the Mycenaean destruction on the mainland from 1200 has to be abandoned.

What the evidence does show is that Greeks at Cnossos ruled for over seventy years after the destruction of the other palaces, and at its destruction, the palace was witnessing a considerable period of prosperity. Most likely, Greeks from the mainland arrived around 1450, seizing Cnossos and consolidating their power by eliminating other bases and destroying the remaining palaces and other sites. This invasion also destroyed smaller villages from plundering and looting. About seventy years later, Greeks from the mainland destroyed their own sects on Crete in a bid to consolidate their power on the mainland, leading to the rise of Mycenae and Thebes, among others.

The idea of a Minoan thalassocracy, which originated with the ancient writers attempting to justify the Athenian naval empire of the fifth century, was perpetuated through the use of archaeology, the absence of fortifications, and the background of the early excavator, Evans. Using the political and military situation of his own nation of Britain, a great fleet devoid of modern shore forts, Evans continued the idea of the ancient Minoan thalassocracy. The removal of the thalassoc- racy allows for a more cogent explanation of the Greek conquest of Crete and the destruction of the palaces in two phases—one in which the Greeks replaced the native population (1450), and a second in which Greeks from the mainland eliminated their fellow Greeks to secure mainland power (1380).

Date added: 2024-09-09; views: 537;