The origin of the terrestrial planets

The golden age of planetary exploration in the 1960s and 1970s provided new insights into the seemingly intractable problem of accounting for the planets that orbit the Sun. On Earth the oldest rocks have an age of 3800 Ma, but they do not provide useful information on its earliest history. The lunar rocks do give us a snapshot of the first 700 Ma of solar system history.

The rocks of the dark maria regions on the Moon are datable at 3300 Ma to 3800 Ma. In the lunar highlands they are as old as 4200 Ma. and rocks that are even more ancient show that the Moon was very hot some 4400 Ma ago. This evidence for a hot Moon Implies that the primitive Earth, being larger, must have been holler still, and therefore volcanic activity and outgassing of the lighter gases must have been commonplace in its early history.

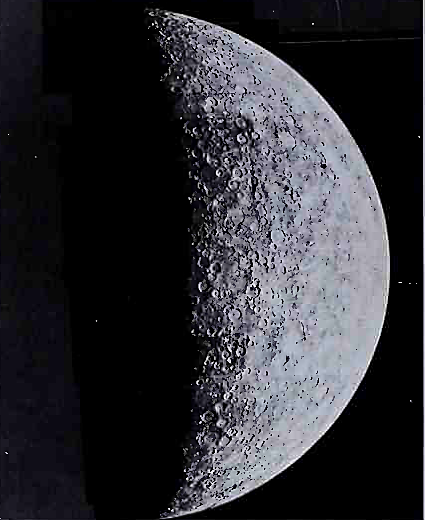

The solar system planets that do not possess thick atmospheres, Mercury and Mars, and also the Moon, suffered intensive bombardment in the past (Figure 2.11). The most ancient lunar rocks are not lumps of lava ; rather they are fragments welded together into rocky masses, having the appearance of collision debris. On Mercury the cratering is at saturation density, no part of the planet having escaped repeated barrages.

2.11: The strong resemblance of Mercury, shown here, to the Moon. Hummocky terrain and faults can be seen in this cratered area

There is no way in which the Earth can have escaped a similar epoch of cratering. but eons of tectonic activity and weathering processes have removed all traces of it. The lunar rocks indicate that the intense bombardment ended about 4000 Ma ago. by which time most of the large rocks in interplanetary space had already crashed into planets and their moons. From the cratered surfaces it can be deduced that one of the final phases of planetary formation was the accretion of fragments onto the planets. It is instructive to trace this argument yet further back in time to see if accretion processes can give a reasonable account of the origin of the planets.

There is no one picture of planetary formation accepted by all planetary scientists. The tentative outline given here is a broad indication of what might have happened after the Sun had condensed from its interstellar cloud. Rotational energy in the collapsing proto-Sun would cause cloud fragments to be left stranded, spinning in orbit round the central massive object. Angular momentum would force this material to orbit in a flat disc, which is why the planetary orbits are almost confined to a plane.

Within this disc protoplanets then condensed out. each with its own gravitational field. Huge numbers of these small protoplanets might have formed, and they would gradually have settled into larger accretions by gravitational coalescence. Certain meteorites, the chondrites, provide us with the best evidence of what probably went on at this stage in the evolution of the solar system.

These meteorites are generally thought to be typical samples of the clumps of particulate matter that condensed from dust and grains in the interstellar cloud. One of the stumbling blocks is explaining how these smallish rocks contrived to form planetary nuclei a few kilometres in size. Once such nuclei formed they swept up further rocks and also collided and joined with each other. In such a manner the rocky planets of the inner solar system grew. The later stages of the process might have involved glancing collisions, which could explain why the rotation axes of the planets arc inclined at a variety of angles to their orbital planes.

An important feature of the accretion model is the kinetic energy contributed by the in-falling fragments. It is estimated that this could have raised the surface temperature as high as 10 000 degrees on the Berth. Another source of heating was the formation of a dense core. Radioactive beating continues to keep the interior of the Earth fluid. I he Moon, being small, soon lost its heat energy: tectonic activity ceased 4000 Ma ago and vulcanism 5200 Ma ago.

Date added: 2022-12-12; views: 672;