Application of Dalcroze Eurhythmics to Music Composition

In the previous section, we outlined the basic facets of the eurhythmics experience: Eurhythmics—rhythmic and purposeful movement; Rhythmic solfege—singing with movement; Improvisation—physical and musical improvisation; and Plastique animie— music represented through motion. In the Dalcroze approach, the concept of time, space, and energy permeate all of these facets. When we move, we are making decisions about speed, distance, and the energy to embody the music. When we sing, we are making decisions about tempo, duration, and dynamics. When we improvise in music, we are making all of the decisions noted above. Finally, when we engage in plastique animie, we are reacting to and representing the music in a purposeful and planned manner.

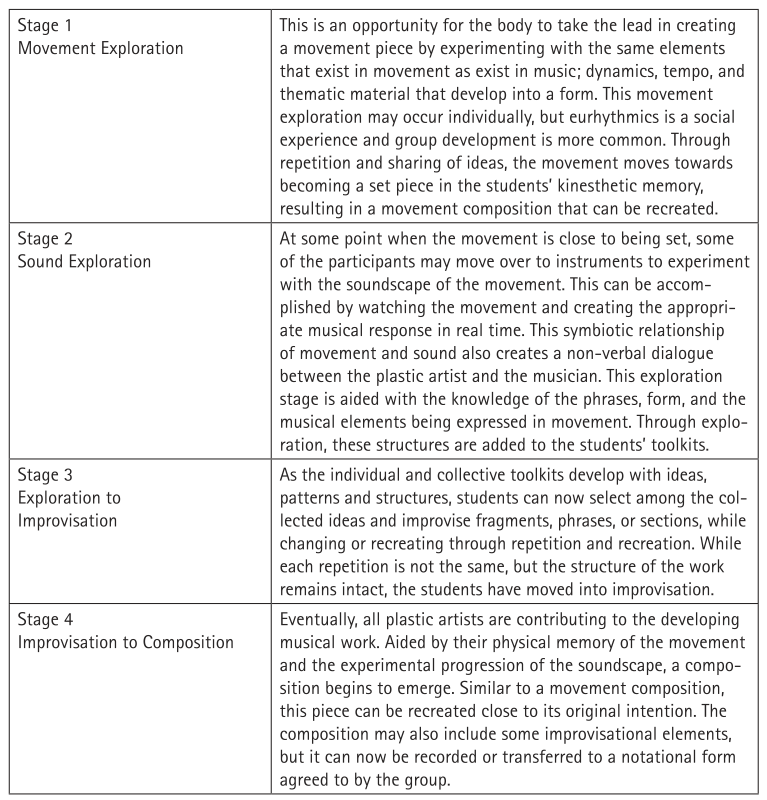

Looking through the lens of time, space, and energy, we propose that participants in eurhythmics may approach the compositional process through four stages: movement exploration, sound exploration, exploration to improvisation, and improvisation to composition. A description of each stage is shown in Figure 17.2.

Figure 17.2. Four stages to composition

Review and Reflection of the Literature. Researchers at Coventry University incorporated Dalcroze Eurhythmies into the teaching ofmusic composition. In this study, thirteen planned sessions of purposeful movement activities relating to the elements of music became learning strategies for composers to draw inspiration (Habron et al., 2012). In setting the design of the project, the authors wrote:

The intention was that the participants experienced each topic bodily before beginning to compose. In order for participants to experience composition in relation to movement, four compositional tasks were set over the course of the project. The design of the project was such that participants would be asked to compose music based directly on their experiences during the sessions: two-part composition; composition involving metric changes; chord sequence with varied bass lines; and theme and variations. (p. 19)

A follow-up interview was held with the participants and four themes emerged: 1) the influence of Dalcroze Eurhythmics on the process and product of composition; 2) the influence of enhancing musical understanding from a kinesthetic perspective; 3) the experience of kinesthetic learning; and 4) the implications for incorporating Dalcroze Eurhythmics into the composition curriculum. It was interesting that the majority of the students reported a positive and somewhat joyful learning experience, but this was not unanimous. That tells us to be aware of barriers to this approach.

These can include perceived body image, self-consciousness, ability to work within a group, and a willingness to take risks (p. 24). While this project involved college students, those same attitudes may exist with young learners as well. In our personal work with gifted/talented children, group work takes enormous energy among the learners and often leads to increased frustrations. Similarly, children with special needs, such as being on the autism spectrum, express challenges with group dynamics, levels of sound, and moving a task to completion. However, many children learn kinesthetically and can build new understandings through movement. Eurhythmics provides teachers with more options to reach efficacy in the music classroom.

Pamela Burnard (2004) has studied children’s music-making from the perspectives of both improvisation and composition. Her research revealed three attitudes of children toward these three tasks:

1. Improvisation and composition as ends in themselves and differently-oriented activities;

2. Improvisation and composition as interrelated entities whereby improvisation is used in the service of making a composition; and

3. Improvisation and composition as indistinguishable forms which are inseparable in context and intention. (p. 38)

One of Burnard’s conclusions is that the approach to teaching/facilitating improvisation may be different than teaching/facilitating composition, even though the outcomes may be indistinguishable. While improvisation is in the moment, using the tools developed in movement and musicianship, composition is goal-oriented with a product that can be replicated. This resonates with the spiral nature of the Dalcroze approach. Improvisation is often the most common activity in movement and in playing. Young children may respond in movement to a teacher’s improvisation. In another case, one child may create a movement improvisation that is accompanied in real time by young musicians using percussion and/or pitched instruments. In this example, improvisation could be one of the goals of the lesson. But, where composition is the goal, a group of students work to create a piece that can be replicated by themselves or others. Students then can agree on a notation system, if needed, and map out their work.

The second approach is that improvisation is used in the service of making a composition. This is more common in a Dalcroze class as a natural progression of learning. Repetition of movement and music improvisation often leads to setting the work. In plas- tique animee, a movement representation of a piece of music, the students’ movements start to become more concrete through repeated listening to the music. Similarly, the parameters of an improvisation start to become more predictable through repeated playing.

The third approach that Burnard wrote about was that improvisation and composition are inseparable in intention. The goal of a task in a Dalcroze class might be to create a movement built on a theme and variations where the variations are improvised, or a rondo form where the “A” section is composed and the sections in between are improvised. This can be realized in movement and in musical improvisation. In all cases, Burnard concluded that children compose through improvisation. However, the goal of the task leads to how improvisation and composition are experienced (Burnard, 2004).

In an earlier study, Burnard (1999) observed 12-year-old children engaged in music improvisation and composition through distinct modes of “bodily intention” Burnard found that children’s experiences were determined by the interplay between body movement, instrument, and preference of instrument. While this study confirmed other studies that showed children compose through improvising, Burnard found that children involved in composing used a reflective synthesis of what was known, and improvisation involved responding with what they could do in the moment.

An additional study by Burnard (2000) concluded with a model that mapped different ways of experiencing improvisation and composition. Four categories were created to indicate that these two approaches are oriented toward: 1) time, 2) body, 3) relations, and 4) space.

These categories resonate with eurhythmics specialists in that time, space, and energy are interrelated and interdependent upon each other. Similar to eurhythmics, Burnard (2000) places the body in the center with time, relations, and space around it. Both improvisation and composition activities need to be preceded with movement activities that allow students to explore how these actions function in movement and music.

Questions often asked by teachers involve notation. Western notation is a complicated system for young children to both decode and encode. Beginning in the late 1990s, researchers looked at strategies where motion could be captured and converted to sound design (Chung et al., 2011). Szu-Ming Chung and Chih-Yen Chen (2011, p. 264) adapted the approach of Dalcroze Eurhythmics in creating an electronic game that involved rhythmic, melodic, and chord progression improvisation activities. Improvisation was designed not to follow a prescribed compositional formula, but to freely create and respond to others, whereas the compositional aspect involved rules where rhythms, melodies, and chords were conceived as teachable elements that encouraged inner hearing and developed notation skills.

The Orff Schulwerk, Kodaly, and Dalcroze approaches all use some form of mapping notation for young musicians. This involves the children creating their composition, then reverse engineering to how it should look on paper. The children are able to show tempo, themes, pitch direction, articulation, and expression in their paper renderings of their works. Dalcroze teachers might give a group’s composition to another group and ask them to interpret it musically. The other group’s interpretation is in itself a teachable moment on interpreting a composition.

Susan Kenny (2013, p. 47) wrote an important article on mapping music through movement in a Dalcroze class. According to the author, moving to and mapping music assists with teaching the musical elements, interpreting a musical score, teaching children how to negotiate in and through space, and problem solving. The detailed musical maps presented in the article were useful in interpreting music through the children’s thought process. Kenny also noted the development of self-control, awareness of surroundings, large and small motor movements, directionality, and creativity. These decision-making processes are needed as precursors for both improvisation and composition.

Date added: 2025-03-20; views: 334;