A Capacities-Based Approach to Music Composition

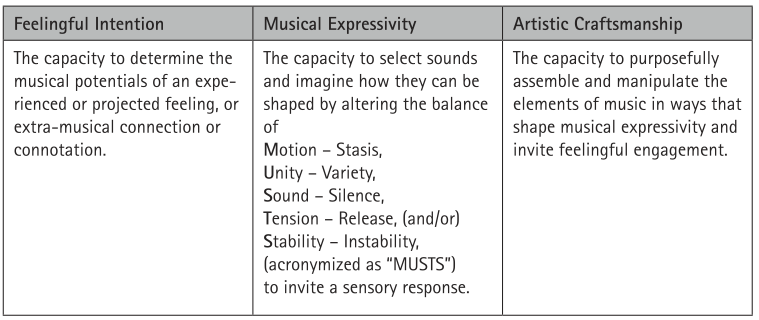

The capacities-based approach (Kaschub & Smith, 2009, 2016a) to music composition focuses on the development of Feelingful Intention, Musical Expressivity, and Artistic Craftsmanship (see Figure 16.1). Feelingful Intention refers to an awareness of the emotion or mood that one might experience in parallel to the sounds shaped by the composer. Musical Expressivity refers to how the changes in the sounds of music are physically experienced within the body. Expressive potentials can be described by referencing five principle-pairs: motion-stasis, unity-variety, sound-silence, tension-release, and stability-instability.

Figure 16.1. Compositional capacities defined

For ease of use, we refer to these by the acronym MUSTS. Each of these pairs exists on a continuum. Expressivity is achieved when a shift toward either end of the continuum is sensed or when changes in the prominence of any of the five principle-pairs is perceived. Such observances give rise to the body-based perceptual knowing that provides critical information for meaning making. The term Artistic Craftsmanship is used to refer to how a composer purposefully shapes the elements of music to create sounds with the potential to be experienced as expressive.

A capacities-based approach positions all three compositional capacities as being of equal importance. Rather than focus solely on imparting technique to advance the manipulation of pitch, time, form, and other musical elements, this approach draws on personal and shared experience to activate the imagination. It looks to feeling and somatic awareness as critical components in the creation of music. As the meanings that result from the composition process cannot be fully isolated from the conditions which influence its evolution, this approach recognizes composing as an artistic process situated in complex contexts that contribute to and shape both the musical product (art object) and its creator. Thus, to fully understand the compositional endeavor, we consider the musical product, the human shaped and reshaped by the process of creating, and the experiential process that develops the two, in reciprocal balance.

Children, left to their own devices, exhibit a natural, intuitive balance in their music making. Feeling, body-based perceptual knowing, and technique are all present in the work of young composers. While formal music study often favors a technique-based approach to composition activities, young composers will, if asked, offer comments that resist such limitations. They describe their music using words that highlight mood or emotion and can readily detail how they feel and sense music in their bodies as they chronicle experiences of calm, expectation, motion, repetition, surprise, tension, and so on. The breadth of these statements is important. Each observation demonstrates the multifaceted nature of the musical experience and suggests that a singular instructional focus has considerable and unfortunate confines. Why, then, has music education walked such a narrowly drawn path?

The Current Challenge. From the latter half of the 20th century through current practice, music education in the United States has focused almost exclusively on elements-focused instruction. Spurred by the Soviet Union’s successful Sputnik launch in 1957, political leaders in the United States turned to science to reclaim global dominance. Other disciplines scrambled. The concept of “musical elements” appeared in Basic Concepts in Music Education in 1958 propelling the elements toward center-stage where they found reinforcement in the Manhattanville Music Curriculum Project (Kyung-Suk, 2006; Thomas, 1970). Ultimately, elements-focused methods eclipsed more open- ended and student-focused pedagogical approaches (Mark, 1996; Stewart Rose & Countrymen, 2016).

This hasty alignment with science-focused conceptions of education preserved music’s place in the school curricula but failed to advance music’s most important dimensions (Reimer, 2022/2003). The after-effects ofthis preservation-driven curricular shift still linger. Beyond the element-laden content of the 2014 Core Music Standards, the initial rollout by the National Association for Music Education presents four pillars— creating; performing, presenting, and producing; responding; and connecting—with graphics akin to those of the periodic table (See https://www.nationalartsstandards. org). Indeed, over the past 60 years the notion of teaching the elements has become so normalized in the curriculum that it dominates PK-12 education as well as the preparation of music teachers.

Unfortunately, this curricular approach has some unintended consequences that eclipse the development of equally important aspects of musical knowledge and artistic understanding. For example, teachers often position lower-l evel skills, such as identifying aspects of melodic construction, patsching the beat, or naming instruments, as end goals rather than as steps toward developing an understanding of music’s expressive value. The demand to evidence “What is it” knowledge and “How to do it” skill often positions teachers to omit instruction addressing “How music comes to have meaning” as they push their students toward benchmarks outlined in school- sanctioned curriculums. Such practices disenfranchise learners through a framework of dominance that denies diversity and individual agency. Further, music activities become atomistic in design and fail to connect with students’ innate physical and emotional relationship with music. Music education conceived of in this way leaves students with a narrowed set of skills to access the meaningful interactions with music that could enrich their lives (Brown & Dillon, 2016).

So how can we reframe our curricular objectives and teaching methods to better reflect the nature and value of students’ interactions with music?

Reframing Our Vision for Music Education. When we began to teach children to compose, we found they were not particularly engaged or connected to their music. We tried to ensure student success through the use of detailed project guidelines. We offered templates which would lead students to the “right” answers. We even provided checklists and rubrics detailing required expectations that specified the use of each musical element. The resulting work might be most aptly described as “cookie-cutter compositions.” The products were nearly identical and lacked expressivity. Moreover, as the students had made very few artistic decisions in creating their work, they had little sense of ownership or interest in their products.

In questioning how we might help improve upon this situation, we discovered that many of the instructional tools being used to ensure student success—often the same types of tools used in performance-focused instruction—were, in practice, preventing our young composers from connecting with the music they were being asked to make. Drawing on philosophy, neuroscience, and creativity research to further understand the generative act of composition, we began to reframe our practices to shift more artistic control to students while simultaneously introducing them to ways of thinking and feeling that could enhance their work (Kaschub & Smith, 2009). In the next section we share the foundations that helped us to shape our focus on musical capacities.

Date added: 2025-03-20; views: 332;