Ancient Phalanx Tactics: How Greeks and Macedonians Ruled Battlefields

The phalanx was the type of battle formation in which the Greek hoplite (heavily armed infantry) was used. It became the dominant form of warfare for nearly a millennium. There are reliefs from Sumeria that show the marching of infantry in lines similar to later Greek infantry tactics. The phalanx typically was an infantry formation where the parallel lines eight to sixteen soldiers deep were spread out across a plain. The phalanx was mainly used on the level field, not on hills. The hoplite soldier was outfitted in heavy bronze armor, a helmet, a breastplate, grieves, a large, round shield, a six- or seven-foot lance, and a sword.

The shield, held in the left hand, protected his left half-side and overlapped with the right halfside of the comrade to his left to cover him as well. The major weakness of the phalanx was the right side, which was not protected by the shield. The phalanx had a tendency to shift to the right to ensure that it was not routed. The Greeks did not use archery or cavalry extensively at this time.

In his epics, Homer mentioned that the Greeks fought in a phalanx formation. This is in contradiction to other passages where he described the protagonists as fighting hand to hand as individuals, as opposed to the organized fighting in later periods. The hoplites who composed the phalanx came from the upper class since they could afford the equipment needed to outfit them. In this dense formation, the army could not move right or left easily; instead, soldiers could merely advance or retreat. The initial tactics of the fighting must have been fairly simple—just an attempt to push the enemy off the battlefield.

Only the first two or three rows would have their spears positioned out, while the remaining lines held their spears vertically and pushed their comrades forward. The offensive weapon used in the battle would have been the spear. Often, if an enemy hoplite fell, the advancing soldiers would impale him with the sharp metal butt of their spears. The battles probably lasted a few hours, with potentially heavy losses if one side became disorganized in retreat. The soldiers would use their swords in the pursuing rout.

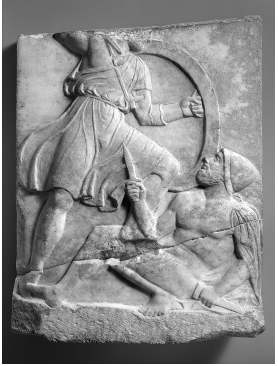

Funerary stele with a hoplite battle scene. (The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Fletcher Fund, 1940)

During the early period, the fighting and tactics were typically one-dimensional. This was probably the type of fighting during the first few centuries until a change occurred in 490, when the Athenians under Miltiades engaged the Persians at Marathon. Facing a larger enemy force than previously witnessed, Miltiades decided to change his tactics. Wanting to ensure that his men would not be outflanked, Miltiades stretched his lines out to make them wider, while at the same time increasing the size of his wings or flanks; but in the process, this weakened and reduced the number of lines in the center.

At the same time, the enemy would attempt to use arrows and cavalrymen to break the line. To counter this tactic, Miltiades ordered his infantry to attack when the Persian cavalry was away foraging, and to run to prevent the Persian archers’ attack. The Athenians’ wings were able to crush the Persian wings before the hoplites turned on the Persian center, achieving a complete rout. According to the historian Herodotus, the Athenians lost only 192 men, while the Persians lost 6,400; although these specific numbers are probably inaccurate, they nevertheless point to the superiority of the Athenian hoplites.

The next major development came during the Peloponnesian War, during the Battle of Mantinea in 418, when the Spartans shored up their line by moving their units from one side to another. This was unusual since such a maneuver was difficult and potentially disastrous. If the units did not move in a coordinated fashion, they could become disorganized where some moved and others did not and allow the enemy to break through a gap in the lines. This tactic had never happened before, and the Spartans successfully achieved victory.

The next major invention was the development of the oblique phalanx, in which one side placed troops at an angle to the enemy. This was further developed by the Thebans under Epaminondas, who arranged his troops at an angle against the Spartans at Leuctra. In addition, he increased the size of the one of his wings, the side closest to the Spartans on his left wing, opposite the Spartan right wing, which would be most exposed. Epaminondas was able to use his enlarged and concentrated force to break through the Spartan wing and rout the enemy.

The most significant development occurred under Philip II of Macedon, who had spent his young adult years at Thebes as a hostage of Epaminondas. He probably learned directly from the general and used his new knowledge to change the Macedonian phalanx. He increased the number of rows of the phalanx to twenty. He then gave the soldiers a longer spear, the sarissa, sixteen feet long, which required the use of both hands. This meant that the shield size had to be reduced, and it was now hung by a strap around his neck and carried by his left arm through a grip to allow the soldier to still hold a spear. These men were now called “foot companions” instead of hoplites, and their job was to hold the enemy infantry at bay. With the sarissa, the Macedonian infantry could keep the main enemy force checked while the enlarged Macedonian cavalry could not only sweep the enemy cavalry off the field, but allow it to break through the enemy lines and attack in the rear, where the opposing generals were stationed.

At the Battle of Chaeronea in 338, the Macedonian cavalry was stationed on the left wing and Philip’s phalanx was at an angle or moved obliquely. Here, the right wing of the Macedonian infantry retreated so that the line was at an angle. Opposite this were the Athenians, who now began to move rapidly, thinking that the infantry was retreating in a disorganized fashion. This created a gap in the line between the Athenians and the Thebans, who were opposite the Macedonian cavalry commanded by Philip’s son, Alexander the Great. With the gap that was created, Alexander and the cavalry attacked the Thebans on the Greek right, where the famous Sacred Band, a select and elite force of 300 men concentrated so as to produce a shock force, was defending. Upon breaking the right wing, Alexander was able to annihilate the Sacred Band and allowed the Macedonians to win the battle.

Alexander used this new form of infantry and cavalry tactics to defeat the Persians. The Greek phalanx was successful until the Greeks met the Roman legions, first in 280 at the Battle of Heraclea in Italy, where the Greek king Pyrrhus won the battle but suffered such great losses that he had to retreat from Italy. And then in 197 at the Battle of Cynoscephalae in Thessaly, the Romans successfully defeated the Macedonian phalanx showing the legion’s superiority in being able to maneuver more readily and defeat the Macedonians. With this victory, the age of the phalanx finally ended.

Date added: 2025-03-21; views: 378;