Persian Empire: Achaemenid Dynasty, Greco-Persian Wars & Legacy

The Persian Empire (also known as the Achaemenid Empire) became the traditional enemy of the Greeks from the sixth to the fourth centuries. The Persians were an offshoot of the Median tribe, located in southwestern Iran, south of Media. As vassals of the Medes, they were controlled by the Neo-Assyrian Empire during the seventh century. A series of civil wars erupted in the late seventh century against Assyria and their allies in Egypt, led by the Medes and Babylonians. With their defeat in 609, the Assyrians essentially ceased to exist, producing a power vacuum in the Near East. The four major powers were Babylon, Media, Egypt, and Lydia in Asia Minor. Babylon attempted to fill this vacuum by attacking the remnants of the Assyrian domains, including the capture of Jerusalem and the destruction of its temple in 570.

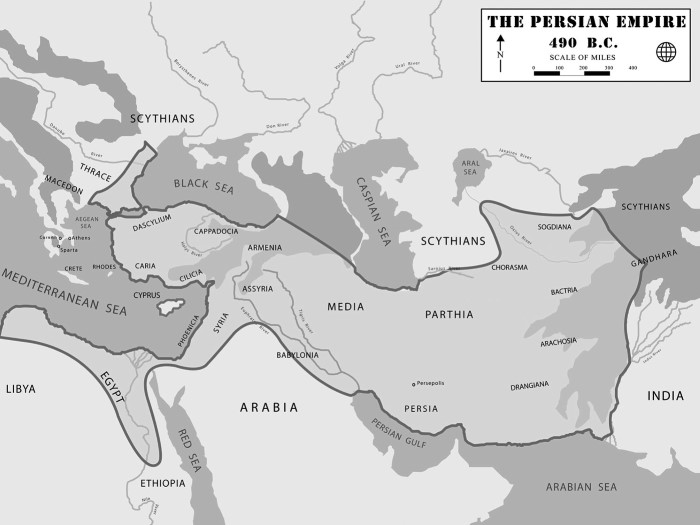

Map of the Persian Empire

During the sixth century, the Medes and Persians struggled for power with Persia under Cyrus, the grandson of the Median king Astyages, defeating him in 550. When Cyrus took over Media and its capital, Ecbatana, he was in a strong position to the east of Babylon and Lydia. Upon his victory, many of the Median vassals rebelled. Cyrus now had to deal with Lydia when its king, Croesus, advanced to seize territory to the east during the upheaval. He crossed the River Halys, marching into Cappadocia and seizing the capital and fortress of Pteria.

As Astyages’s brother-in-law, Croesus may have desired to reinstall his brother- in-law, but more probably, he wanted to use the destabilized situation to seize more land. This led to the Battle of Pteria in 547, when Croesus and Cyrus fought to a draw and the smaller army of Croesus retreated to Sardis. With winter approaching, Croesus disbanded his army, thinking that Cyrus would do the same. Instead, Cyrus rapidly advanced to Sardis, taking the city in 546. Cyrus left a local Lydian, Pactyes, in charge of collecting tribute, but he rebelled, forcing Cyrus to send in a Median general and army to reduce the region.

Cyrus now controlled two of the four kingdoms, but he had to deal with the rebellions by Lydia and former Median vassals. Cyrus appears to have made a campaign to the east to Bactria to deal with some of these former vassals. He probably did not attack the Indus; instead, he restored order, including the establishment of garrison towns, including Cyropolis in the Northeast region, perhaps modern Khujand in Tajikistan. It would later become Alexander the Great’s city, Alexander Eschate.

During this same time, Babylon and Persia were engaged in a standoff. It is possible that there were several battles leading up to the war that began between the two in 539. The Babylonian king Nabonidus had become unpopular by advancing the god Sin over the traditional god, Marduk. He left his son in charge of the defense while he continued building his religion. When Cyrus attacked, the Persian army defeated the Babylonian army and marched toward the capital. Nabonidus’s son died in battle, while the king’s fate is unknown; some accounts have him being killed, while others say that Cyrus pardoned and exiled him, a common practice that he was known for. Cyrus declared himself to be the rightful successor of the Assyrian kings and the defender of Marduk. He also restored the Jewish exiles to Jerusalem, and he may have used them as agents in his attack on Babylon.

During the next few years, Cyrus would continue his conquest and consolidation of the empire. He had two sons, Cambyses and Bardiya, and died in 530 fighting the Massagetae in central Asia, who were perhaps Scythian. His elder son, Cambyses, now became king, assassinating his brother, and continued his father’s conquest by moving south to Phoenicia and Cyprus by 525. In 526, the pharaoh Ahmose II, Egypt’s last great ruler, had died. His son faced rebellions, allowing Cambyses to defeat him at Pelusium and take the country. Ancient historians portrayed Cambyses as erratic and antagonistic to the Egyptians where he supposedly lost his mind, causing him to kill his brother, and even the sacred Egyptian god-bull, Apis. But this is probably a later invention since Cambyses in 524 helped in the sacred funeral procession of the Apis.

Cambyses now received submission from Cyrene and undertook a campaign in the south that established a fortress at the Second Cataracts, deep in the south. He then moved north to deal with a rebellion in 522; he was wounded and died of his injuries. The rebellion was by a certain Bardiya. Bardiya was the brother of Cambyses who supposedly died in one story. There are several theories related to this figure. One derived from the ancient sources is that he was an imposter, who looked like Bardiya and was put on the throne by Persian nobleman; while another theory has it that Bardiya actually did not die before Cambyses and waited until Cambyses died before claiming the throne. Darius I, the son of the satrap of Bactria and one of the leading families, led the Persian forces against the rebel. The preferred story given out by Darius was that Bardiya was an imposter; but if the rebel was actually Bardiya, then Darius had led a rebellion against the son of Cyrus who should have been the king, which was probably the most likely situation.

Darius now assumed power and had to face a series of revolts by those loyal to Bardiya throughout the entire heartland of Persia, including Media, Assyria, and Egypt. During the next year, he defeated a total of nine pretenders to the throne and reestablished his power throughout the empire. This included the retaking of Babylon from a pretender who called himself Nebuchadnezzar III and claimed to be another son of Nabonidus. This was followed the following year by another rebellion led by Nebuchadnezzar IV, which forced Darius to besiege the city again. With this conquest, the powerful city of Babylon finally fell to the Persians. Darius now began to reestablish Persian authority by campaigning in Egypt to consolidate Cambyses’s recent conquest. A pretender had stirred up a rebellion in Egypt, probably due to the Persians demanding high taxes, and Darius now moved against him; although Persia was successful in retaking control, Egypt would continually rebel throughout Persia’s rule. After securing the interior of the empire from further trouble, Darius was able to begin more conquests and reforms.

After taking Babylon and dealing with Egypt, Darius advanced to central Asia to begin his campaign there in 518. After campaigning in Aria and Bactria, he then moved toward the Taxila in modern Pakistan and the Punjab. In 516, he spent time preparing for the invasion of the Indus in Gandhara. He conquered the region of the Indus in 515, moving to modern Karachi. He then marched back to Persia through the south in Arachosia and Drangiana, the latter populated by a tribe related to the Persians. He returned in 514 to the heart of Persia before planning his next campaign to the far north.

The region from the Danube to the Don rivers was inhabited by the Scythians, an Iranian tribe that the Persians claimed to oversee. The Scythians, if left unchecked, would disrupt the rich trade along the Black Sea. Darius planned to deal with the tribe by moving from Susa north to the Hellespont in the spring of 513. The Scythians did not directly engage the Persians but rather used hit-and- run tactics while using scorched-earth practices to deny the Persians supplies. Darius crossed the Hellespont and moved north and east around the Black Sea into modern East Europe, the Ukraine, and southern Russia. While the Scythians avoided battle, they also lost their best land. Darius continued to move eastward. He halted his campaign at the Volga and returned to Thrace.

In essence, both sides failed, Darius did not bring the Scythians to direct battle and win, while the Scythians lost valuable land and produce. The Persians disrupted the fabric of society in Scythia and weakened their political and military power but failed to subjugate the Scythians, forcing Darius to abandon his planned control of the Scythians, especially in the west.

After his return from Europe and the Scythian invasion, Darius returned to Susa. In 499, the Ionian cities rebelled, bringing Persia and Greece into direct conflict. Athenian ships landed and helped burn Sardis before retreating, which forced the Ionians to fend for themselves. During the next five years, the Persians reduced the Ionians, winning a decisive battle at Lade.

With the conquest of the Ionians, Darius now planned to punish the Athenians by mounting an invasion of Greece. In 492, he sent an army to Macedon, where King Amyntas I had submitted to Persia in 513, but a storm destroyed the fleet, forcing Darius to alter his planned attack on Greece. In 490, the Persians sailed across the Aegean Sea and attacked Eretria at Euboea. After taking the island, the Persians sailed to Attica and landed at Marathon, where they were defeated by the Athenians.

In 486, Darius’s son, Xerxes, ascended the throne and planned a new and larger invasion of Greece. In 480, his army advanced across the Hellespont, taking Thessaly and, moving south, taking and burning Athens. There, at Salamis, the Persian fleet was defeated by the combined Greek fleet under Themistocles and Athens. Xerxes fled but left an army behind at Thebes. In 479, a Spartan-led army defeated this Persian army at Plataea, and supposedly on the same day, the fleet at Mycale in Asia Minor won a similar decisive battle.

With Xerxes’s setback in 480-479 in Greece, the Persians now attempted to regain the initiative, but their fleet was again destroyed in 469. In 465, Xerxes was assassinated and his son, Artaxerxes, took over, ruling until 424. He gave asylum to Themistocles after his ostracism in 471 who wandered in Greece until going to Persia. Artaxerxes had to deal with a rebellion in Egypt. Persia now decided not to directly challenge the Greeks, but rather to fund opposition in Greece.

After Artaxerxes’s death in 424, a series of palace rebellions took place, with Xerxes II dying after only two months of rule. His half-brother, Darius II, took over and ruled until 404. Artaxerxes II succeeded his father, Darius, and had to wage a civil war with his brother, Cyrus the Younger. The historian Xenophon relates how Artaxerxes defeated and killed Cyrus in 401 at the Battle of Cunaxa. After this victory, Artaxerxes ruled until 358. Artaxerxes had to work with Sparta first by supporting Sparta’s enemies and then betraying them and coming to an agreement with Sparta and forcing his Greek allies to agree to it, resulting in the Peace of Antalcidas (King’s Peace). He then had to deal with Egypt, which had successfully rebelled against him early in his reign. In 373, he decided to retake the region. His generals failed, though, leading one of them (Datames) to lead a rebellion against him during the revolt of the Satrapies, from 372 to 362.

Upon his death in 358, Artaxerxes was succeeded by his son, Artaxerxes III, who ruled until 338. Like his father, Artaxerxes III had to deal with a series of rebellions. The first was in Asia Minor where he was initially defeated by the satrap, but in 353, he defeated the rebels, retaking the region. He then attempted to retake Egypt in 351 but was defeated and forced to retreat; this caused the regions of Phoenicia and Cyprus to rebel, and it ultimately would take nearly ten years for him to reduce the regions in 343.

After this, he began a new conquest of Egypt, succeeding to dislodge the Egyptians and retake the country. He imposed new taxes and punished the local Egyptian rulers and religious leaders. Artaxerxes returned to Persia and settled the regions. In 338, Artaxerxes III died; one source said that it was from natural causes, while Greek literary sources indicated that he was poisoned by Bagoas, one of his generals. Artaxerxes IV, the son of Artaxerxes III, ruled from 338-336 and had to handle the growing threat of Philip II of Macedon. He attempted to eliminate Bagoas, who had put him on the throne, but instead was killed by Bagoas, who put Artaxerxes’s cousin Darius III on the throne. Darius III ruled as Persia’s last king until Alexander the Great defeated him, taking over the Persian Empire.

When he founded his empire, Cyrus the Great created four great capitals to rule his empire: Pasargadae (which was replaced by Persepolis under Darius the Great), Susa, Ecbatana, and Babylon. He probably created the satrapy, an administrative unit ruled by hereditary governors. They were given extensive freedom, allowing them to rule virtually as kings themselves, so long as they provided tribute and soldiers to the real king’s empire. The satrap ruled as a civilian governor, while a general took charge of the military functions. There were between twenty and thirty satrapies.

Cyrus was also responsible for the new army, including the creation of the 10,000-man unit known as the Immortals or Royal Guards. The army was a mixture of various troop units from throughout the empire. He also created a royal road system and postal service for official communications. The road system linked all of the satrapies with the main capitals; the most famous of these was the Royal Road from Sardis to Susa. It was probably under Darius that the Persians introduced the gold Daric and silver Siglos coins, creating a bimetallic monetary system. Darius also reformed the tax system so that each satrap tailored it to its own productivity and capabilities. It was under his rule that there was a codification of laws and the establishment of the capital at Persepolis.

The Persian army was composed of both infantry and cavalry. The infantry had various units. For instance, the heavily armored Immortals were the king’s bodyguard and crack troops. There were the sparabara (shield bearers), who carried wicker shields and six-foot-long spears. Although they were well trained, they were not a professional army and were landowners when not in military service. They would form a wall of shields that was capable of withstanding attacks by arrows, but not the highly trained phalanx of the Greeks.

The main offensive Persian force was the cavalry. The most important troops were on horseback and in chariots. While the early chariot archers were crucial in battle, they later became more ceremonial. The cavalry not only used spears and swords, but bow and arrows. It was this group that gave the Persians their most important force and caused the Greeks to constantly deploy their men so as not to be outflanked. There were also camel cavalry, and perhaps war elephants as well, but the evidence is not conclusive that they were used much. The Persians also used a strong navy, developed mainly by the Phoenicians and augmented by Ionians.

The Persian Empire was the first true multiethnic and cultural world empire. Its creation occurred through the military conquest of Cyrus and its downfall after being conquered by Alexander the Great.

Date added: 2025-03-21; views: 477;