Challenges of Composing Projects

There are challenges for teachers to be aware of before starting a composing project, particularly one that will require student collaboration. Anyone who has ever been involved with a group project is aware of some or all of these pitfalls. Obstacles to effective group interaction include (a) off-task talk; (b) social loafing, in which some students allow other students to do all of the work; (c) unequal interaction; (d) negative interactions such as anger, ridicule, and racist or sexist remarks; (e) working independently instead of together, or splitting up work instead of collaborating; (f) low-quality interactions that do not involve much thinking; and (g) reinforcement of students’ beliefs that some students are not capable of contributing (Chinn, 2010). In addition to these obstacles, I will briefly describe other variables that may influence collaborative composing projects.

Time.In my own research, I found that when groups had less time to compose their pieces, the amount of off-task talking and playing was reduced, with little impact on compositional quality (Hopkins, 2015). As Parkinson’s Law states, “Work expands so as to fill the time available for its completion” (Editorial, 1955). I recommend adding time to the project as needed rather than providing students with more time than they need from the outset. In my research I noted that productivity increased as the deadline neared.

Friendship and Gender.A number of researchers have found friendship to have a positive influence on student interactions and the resulting composition (c.f. MacDonald, Miell, & Mitchell, 2002). Many of these research findings occurred with elementary or middle school students. In my research with high school students (Hopkins, 2015) I found that some groups of close friends were prone to high levels of off-task talk and social loafing, in which some students were allowed (or expected) to do all the work.

Some researchers have found that in mixed gender groups of students who are nine to 11 years old, girls take control of musical tasks and, in general, that these groups cooperate less well than single-gender groups (Burland & Davidson, 2001; Morgan, Hargreaves, & Joiner, 1997). However, in my research of high school students (Hopkins, 2015) the mixed gender groups had high levels of collaboration. The two weakest collaboration scores were in the all-female groups. One possibility for this contradictory finding is that gender groupings may vary in their effectiveness at differing levels of maturity and development. Teachers should definitely take into consideration the age, gender, and friendships among students when forming collaborative composing teams. As Berg (1997) noted, gender influences the status of individuals within chamber groups, and gender can influence the linguistic forms used and the quality of interactions.

Coaching Teams.Ensemble directors often provide direct instruction and may struggle to adapt to their new role as a facilitator. You do not want to hover over students as they engage in the creative process, so take a few minutes before the composing begins to provide suggestions about how to help and support each other as a team. Explain to your students the importance of balanced collaboration and participation to help reduce the amount of time spent off-task. Advise students to seek you out if their group is experiencing a decline in productivity. As students compose, be prepared to differentiate instruction by providing higher levels of guidance to groups with less experience, and greater levels of independence to groups with more experience. If you check in on a group and they appear to be distracted, remember that sometimes students need to take a creativity pause by talking about something unrelated to the task. Sometimes the best musical ideas are generated after a brief period of being “off-task.” When students give a “work-in-progress performance” for you they may make negative comments about their compositions (e.g., “It’s not very good”). Remind them that they can always make changes. Ask them to brainstorm how they might further develop their musical ideas to make the piece more exciting. Resist the urge to propose your own solutions! Some slight changes in pitches or rhythm or dynamics often make an enormous difference in how music is perceived.

Notation.A composition needs to be preserved in some type of medium. It can be an audio recording, or a score of some type. The creative process works best if students are encouraged to develop well-formed musical ideas before they are required to record or write the ideas on paper in standard notation. I think that preserving compositions using standard notation is extremely valuable for students, however, if students are notating as they compose, rather than after they have a well-formed idea, the process of notating will slow down and may interfere with the creative process. Many students will need help translating their musical ideas into correct notation. They may also write notes on paper first and then discover how those notes sound by playing on their instrument, which is in some sense the opposite of composing. In the early stages of the creative process, it may be helpful to make audio recordings or notational sketches of preliminary ideas and translate the finished product into a score using standard notation.

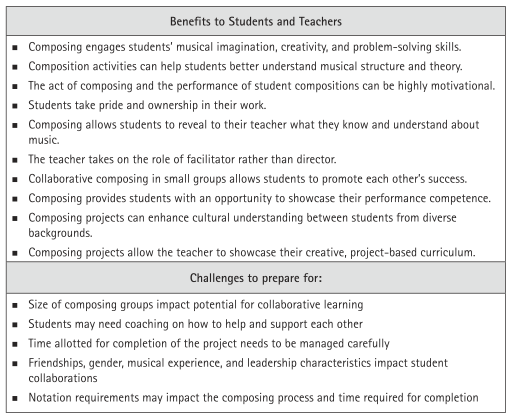

Figure 32.1 provides a succinct summary of the benefits and challenges that orchestra teachers should prepare for when planning composing projects.

Figure 32.1. Considerations for composing in orchestra

Date added: 2025-04-23; views: 321;