Historical Perspective on Composing in Schools in Germany

For a long time, singing was the only activity intended for general music classes in Germany. This was still true in the 1920s when Fritz Jode (1928) wrote his book Das schaffende Kind in der Musik (The creative child in music). By promoting the idea to develop creativity in music education he did not commit to music composition, but instead used the argument to justify music in schools. He argued that singing was a creative activity and creative powers were needed to sustain life. This thought is typical of the progressive education movement (Reformpadagogik) that was influential in music education at that time. It facilitated later attempts to establish composition pedagogy.

Carl Orff’s Schulwerk can be considered another precursor. Based on his work at the Guntherschule in Munich in the 1920s Orff developed his well-known approach. Creating music is crucial here. “Improvisation is the starting point of elemental music making” (Orff, 1978, p. 22). What is most important is that he provided a strong argument for considering student compositions as valuable. However, even though Orff instruments can still be found in almost every music classroom in Germany and Austria, Orff’s music for children is hardly used; his Schulwerk largely fell into oblivion.

During the 1960s, music education in German schools underwent changes. Music appreciation replaced making music as a key part of music lessons. Singing traditional songs was no longer the main activity. In his influential book Unterweisung im Musikhoren (Teaching music listening) Dankmar Venus (1969) argued that in music education the content of teaching must be perceived as music practices.

Determining the music curriculum, he suggested, should be based on the distinction between production of music (improvising and composing), reproduction (performing), reception of music, transposition (transforming music into other forms of medial expression like dancing) and reflecting on music (e.g., by addressing historical and cultural contexts). However, it is not by accident that the title of his book emphasizes listening to music. Even though Venus claims that all music practices are equal and independent, they all seem to serve music listening pedagogy in the end.

There were counter movements to an art-oriented approach to music education. Since the beginning of the 1970s, new ideas emerged that were inspired by philosophies and practices of post-serial music and composers like John Cage. In these views, improvising and composing was crucial, strongly linked together, and difficult to separate. Gertrud Meyer-Denkmann (1972, 1977) was a music educator, composer, and musicologist who developed a concept of music education and methods that were based on structures and practices of New Music. It focused on experiments in sound, sought to understand the process of musical experience, and rejected the idea of the autonomous artwork. Aleatoric music, performance art, and sound collage provided the model for composing in the classroom instead.

In accordance with the political Zeitgeist of that time this was justified by the desire to change social conditions. Avant-garde aesthetics and social criticism were the basis for developing a concept that encouraged students to work as many composers of New Music do. Together with several co-authors Rudolf Frisius published the textbook Sequenzen in 1972 with similar intentions and comparable content. What students do, the authors wrote, is “analyze given sounds beyond tonality and measure. In the process, they discover elemental sound qualities and structures” (Frisius & Arbeitsgemeinschaft Curriculum Musik, 1972, p. 12).

Composers play an important role in the history of composition pedagogy in Germany and Austria. Dieter Schnebel, who composed many pieces for children, wrote the preface for Gertrud Meyer-Denkmann’s book Struktur und Praxis Neuer Musik im Unterricht (Structure and practice of New Music in the classroom). The few publications of the composer Paul Dessau about music education in schools (Dessau, 1968) are also interesting to note even though his ideas received little attention. Based on his experience as a music teacher he called for a production approach to music education, emphasizing that inventing music is essential for children’s musical development. Of particular importance are the community operas Hans Werner Henze produced at the festival Cantiere Internazionale d’Arte in Montepulciano/Italy and in Deutschlandsberg/Austria (Henze, 1984 and 1986).

He took a unique approach to music education by allowing the participation of many people in composing music theater pieces. This effort was a type of cultural education motivated by a desire to link lay music and amateur art to professional music and art. As a Marxist, Henze was driven by the wish to contribute to social development. He considered it his duty to engage actively in the process of developing social awareness and critical faculties toward a humane society. These were not school-based projects but there was great interest in Henze’s work, and his community operas served as a model for similar projects within or in cooperation with schools intending to promote cultural participation.

Since the 1980s popular music has increasingly found its way into the curriculum. This was associated with changes in classroom activities. On the one hand, pop and rock music became increasingly accepted as teaching content. On the other hand, more emphasis was placed on making music in the classroom. In addition to singing, music listening, analyzing music, and learning about music history, students were playing music on different instruments. Simple arrangements were written suitable for students without any prior experience. Volker Schutz (1981 and 1982), one of the pioneers of popular music education in the general classroom in Germany, stressed that teaching popular music must be guided by the everyday life experiences and musical activities of the students.

He was convinced that understanding music is only possible if students have the opportunity to perform and, furthermore, to invent music. Composition, in his view, is key to understanding music. Based on this popular music pedagogy Schutz suggested courses that lead to students’ working out their own songs. He was fully aware that this was a challenging goal. As then, songwriting remains a rare part of the music teacher education curriculum that is dominated by performance and musicology. The shortcomings in music teacher education still concern composition pedagogy regardless of the music genre. Because of these obstacles in implementing teaching methods for composition, it can be assumed that many innovative concepts remained on paper. At the least, it takes a long time from developing models of composition pedagogy, developing the curricula in different states, and creating the prerequisites in teacher education to get to the actual implementation in the classroom.

This is one reason why collaborations with artists are popular. Since the late 1980s many cooperative school projects with visiting composers have been initiated, often supported by concert halls or similar institutions. Response served as a model, imported from the UK and for the first time realized in 1988 with musicians of the London Sinfonietta and the Ensemble Modern (Voit, 2018a). Since then, different series of comparable projects have been launched: Querklang, located in Berlin, or Klangradar3000 in Hamburg. In many cases, however, these programs also have other objectives.

The students’ compositions refer to a specific musical work, almost always from the field of New Music. The aim of encouraging students to compose and the desire to break down barriers and to provide access to contemporary art music are often blurred. Music education and music promotion may overlap, particularly if the concert hall involved is mainly interested in audience development. Additionally, the artists involved might not be familiar with the classroom situation and might not be well prepared to act as educators. In these circumstances, conflicts and misunderstandings may arise (Rolle et al., 2018). However, that does not change the fact that the large majority of these projects are carried out with high commitment by the visiting composers and the teachers involved, and that they can open up spaces for creativity.

Parallel to the growing number of collaborative composition projects, renewed impetus for composition pedagogy was provided by several publications during the 1990s. Ortwin Nimzcik (1991) wrote a book called Spielraume im Musikunterricht (On margins in the music classroom), discussing pedagogical aspects of creative work in music. He also based his ideas on composition practices from the area of New Music, but in addition he referred to concepts of education. Building on this theoretical framework, Ortwin Nimczik published assorted teaching materials during the following years and was also involved in launching the composition competition called Teamwork for music classes and ensembles in schools inventing pieces of New Music, which is organized by the German music teacher association BMU.

The lively discussions on aesthetic education held in several educational disciplines during the 1990s in Germany provided important ideas for developing composition pedagogy. At stake was the meaning of arts education in the school curriculum as well as the question of how teaching music could contribute to education (in German “Bildung”). In retrospect, this debate might have been a reaction to emerging neoliberal ideas that were feared to affect education by focusing on measurable goals, efficiency, and usefulness. Insisting on the intrinsic value of the arts and on the meaning of aesthetic experience for education can be seen—and in fact was seen—as acts of resistance. This has consequences for how music education views itself.

Thus, the philosophical discussion affected concepts of good teaching in the arts. Against this backdrop, music education should be more than teaching and learning facts about music; it is not only about acquiring musical skills. The discussion draws attention to the aesthetic dimension of music and the importance of creative processes offering opportunities for musical experience (Rolle, 1999). Based on this theoretical framework Christopher Wallbaum (2000) developed a model of teaching composition—he speaks of “producing music”— using an approach that is oriented both toward the process of composing and the created product. Aesthetic experience and music as aesthetic practice are core concepts of his philosophy of music education.

The model suggests providing spaces where the students could discuss the quality of their work. If composition is collaborative in nature, there must be opportunities to exchange ideas and to discuss intermediate results in order to come to joint decisions. There must be room for what Rolle and Wallbaum (2011, see also Rolle, 2014) call “aesthetic argument” Teaching composition raises issues of evaluating music, and teachers ought to find ways to give students the responsibility for negotiations on the artistic quality of their music.

Typical Composition Assignments and the Tradition of “New Music”

In German music textbooks and other materials for teachers one can find numerous composition tasks that are oriented toward popular music. Many of these focus on composing a class song or a rap. There also are suggestions for lessons on electronic music production. Nevertheless, assignments that refer to the tradition of New Music still dominate.

As mentioned before the term “composition” is strongly connected to art music and was not used in educational contexts for a long time. Matthias Schlothfeldt (2009) even distinguishes between composition assignments and creational tasks (in German “Gestaltungsaufgaben”). The latter are provided to the students by the teachers and are embedded in a larger teaching context. Solving a creational task serves as a means to the end of teaching other musical skills or competencies. Creational tasks serve to apply or secure learning outcomes, for example, securing knowledge of the rondo form by inventing a rondo. In a composition task, composing is an end in itself and the students can only set their own composition assignment. Here the students themselves determine the means and the approach, and are responsible for their own decisions. They are less guided by external guidelines. To continue the example, the students only compose a rondo if this is the form they need to express themselves musically in the way they want.

The need to conceptually differentiate tasks, to the extent of using different names, demonstrates the cultural depth of the term “composition.” This is closely connected to the idea that in composing, an autonomous artist goes through a self-determined process that serves no other purpose than to create a composition. Helmut Schmidinger (2020, p. 192), however, points out that the term “composition” should also be used for putting together known elements in order to relax the pedagogical approach to composing. We agree with this view and therefore, we identify all assignments that ask students to invent music as “composition assignments” in the following.

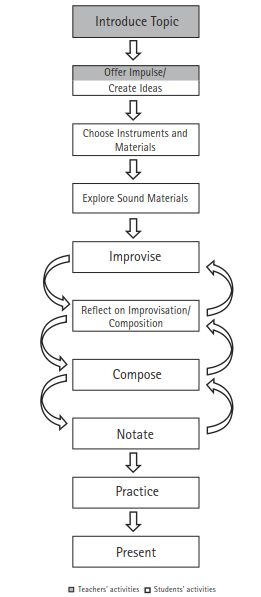

There are different models suggesting how the composition process can be structured in pedagogical contexts. Listening and reflection are essential elements in these models. We will present one of those. Renate Reitinger (2008) distinguishes 10 phases in the composition process (see Figure 37.1).

Figure 37.1. Structure of the composition process (Reitinger, 2008)

Many assignments are structured accordingly. We will present a couple of these assignments that are descriptions of lessons as they are found in textbooks for the general music classroom.

Date added: 2025-04-23; views: 238;