Advancing Pedagogy through Teacher Assessment

In this section, I briefly describe three music teacher assessment frameworks and offer composition-specific modifications. These may be useful self-assessment tools and promote dialogue with evaluators and administrators. While these music-specific resources may certainly assist music teachers—and other stakeholders (e.g., administrators, evaluators)—as they exist, specific to this chapter, they generally conceptualize and describe music teaching as emphasizing performance-related skills, with few examples of using these frameworks to improve composition pedagogy. While they may not describe composition pedagogy with the same level of priority or nuance given to teaching music performance, they are readily adaptable.

Danielson. The Framework for Teaching Evaluation Instrument, 2013 Edition (Danielson, 2013), presents aspects of a teacher’s responsibilities that have been documented through empirical studies and theoretical research as promoting improved student learning . . . [that] seek to define what teachers should know and be able to do in the exercise of their profession. (p. 1)

The framework comprises four domains: planning and preparation, classroom environment, instruction, and professional responsibilities. Within these domains are nested 22 components, each with multiple elements and indicators, and four levels of performance (i.e., unsatisfactory, basic, proficient, distinguished). For example, within the domain of planning and preparation, one component is demonstrating knowledge of content and pedagogy. Two elements of that component are “knowledge of content and structure of the discipline,” and “knowledge of content-related pedagogy,” and two indicators of that element are “lesson and unit plans that reflect important concepts in this discipline” and “feedback to students that furthers learning”

More recently, the Danielson Group (2019) published a series of music education scenarios. Not a prescriptive document, it provides example scenarios, few of which relate to composition. Those that are included most often appear at the “distinguished” level. For instance, consider this “distinguished” example of “setting instructional outcomes”: “Using poems created in language arts class, the students, working in dyads of poet/composer, will compose and record original songs using GarageBand software” An example of “proficient” in “Demonstrating Knowledge of Resources” is: “The music theory teacher is taking an online course to learn how to better use GarageBand with her students”

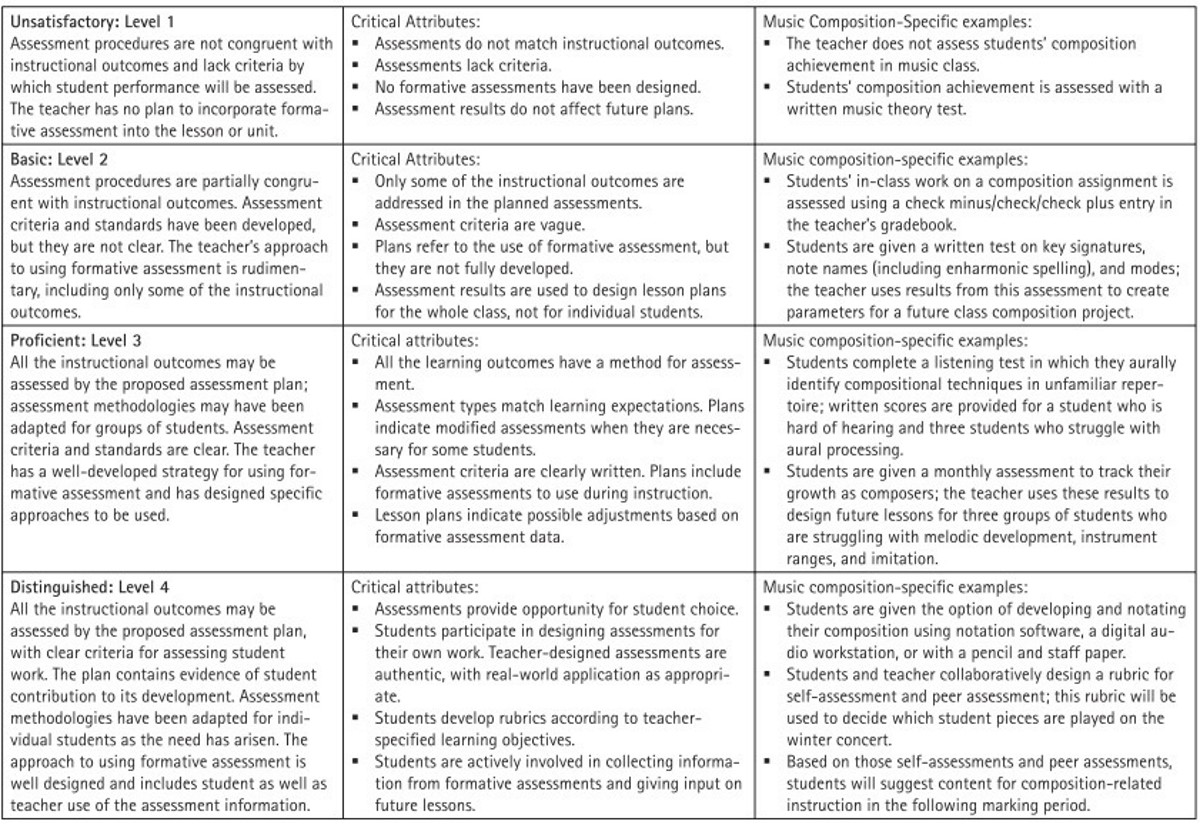

While I am glad that examples of composition instruction appear in this document, relatively isolated examples at “proficient” and “distinguished” levels could reinforce misperceptions that teaching composition is a pursuit for teachers with composition training, or for particularly advanced students with enough advanced theory knowledge to begin composing. A broader range of examples could help teachers and other stakeholders conceptualize what it might “look like” to describe composition-related pursuits in this framework. With that in mind, I present examples of composition- related scenarios for the component “Designing student assessments” that might be observed in a high school instrumental music classroom pursuing two hypothetical goals I created earlier in this chapter. These appear in Figure 41.2, along with descriptions of levels and their critical attributes.

Figure 41.2. Descriptions, critical attributes, and music composition specific scenarios for designing student assessments

Doerksen. Doerksen (2006) offers a resource for evaluating music teachers who offer instruction to performing groups. While noting that this instruction “is usually limited— rightly or wrongly—to the development of individual and group performance skills,” and suggests that a relevant performance indicator might be “teaches to and assesses specified [NAfME] National Standards for Music” (p. 23), the text primarily presents music teachers as large ensemble rehearsers. Still, Doersken offers useful documents, evaluation considerations, and frameworks for conversations between music teachers seeking to incorporate composition and administrators.

Doerksen provides job descriptions for ensemble-based music teachers, including responsibilities at varying degrees of specificity. While sample responsibilities include broad references to teaching to and assessing national standards, more specific references are primarily related to music performance, such as: “Conducts rehearsals and performances, demonstrating understanding of differences in style among various types of music” or “Identifies and diagnoses problems in individual and group performance skills, and prescribes appropriate and effective corrective feedback” (p. 13). While Doerksen’s text is explicitly oriented toward teachers of music performance groups, a teacher whose teaching assignment includes music performance groups and who seeks to improve their composition pedagogy could negotiate that as part of their job description with their supervisor. For example, the descriptor “designs or selects and uses planned sequences of instruction so that students acquire skills in string technique and music reading” (p. 13) could be expanded to include “skills in composing music for string instruments” or “skills in creating original music.”

Similarly, in conversations about goals and objectives, Doerksen suggests that a pre-observation conference might include discussion of class activities, including, “a warm-up period, a time for working on group technique, and a time for working on repertoire” or establishing “position, breathing, and tone production” with beginning students. In a pre-observation conference with their principal, a teacher might explain that the lesson being observed will also include time for skill and knowledge development related to composition. This might include not only explicit time devoted to students composing, songwriting, or producing, but also intentionally-selected activities to help students develop skills and capacities for creating music.

For example, students might develop aural skills by learning important elements of their repertoire by ear as a warm-up (e.g., Shewan, 2009; Snell, 2015). In another lesson, they might engage with cinematic or literary works and make connections to a piece they are studying (e.g., Sindberg, 2012). They might also develop interrelated capacities as performers and listeners using Kaschub and Smith’s (2016) principle pairs continua of motion-stasis, unity-variety, sound-silence, tension-release, and stability-instability to discuss repertoire they are rehearsing. As Kaschub and Smith note:

Music-making and the capacities that support it are dynamic in nature and execution. Listeners who tap their feet or drum on their steering wheels are adopting performer actions as they contribute their own sounds, performers who wonder why a composer has crafted a line in a particular way are exploring the composer’s intent, and composers who imagine their work as it will be experienced by an audience assume the listener’s ear. (p. 39)

Onuscheck, Marzano, and Grice. Based on Marzano (2017), Onuscheck et al. (2020) offer an art- and music-specific instructional model with three overarching categories (i.e., feedback, content, context) and ten design areas (e.g., using assessments, building relationships, communicating high expectations). Within these design areas, Onuscheck et al. articulate 43 more detailed elements (e.g., formal assessments of individual students, academic games, probing incorrect answers with reluctant learners) and offer “additional, subject-specific strategies that teachers can use to increase students’ response rates” (p. 5). Similar to Danielson’s performance levels, Onuscheck et al. provide five-point rating scales for teacher self-reflection.

Like Doerksen (2006), Onuscheck et al. (2020) cite four artistic processes in National Core Arts Standards as a reference point for establishing goals; however, the majority of the text is written through a lens of a performance-centric music education. For example, the authors state “celebrating success in music has two facets: (1) celebrating the ensemble and (2) celebrating the individual . . . in relation to the ensemble” (p. 20) and seem to conflate learning to perform a piece of music in an ensemble with “the process of creating music” (p. 25). (To be clear, while there are creative elements of preparing a piece of music for performance, National Core Arts Standards clearly delineate performing music from creating original music.)

Similarly, while authors acknowledge that engaging students with composition could be part of what a teacher does (e.g., “music portfolios could consist of . . . original compositions or lyrics” [p. 27]), statements about performance-centric objectives are more frequent and more explicit (e.g., “the teacher will ask students to use a pencil to mark sections of the music that require reminders” (p. 63) or “when the teacher stands at the podium or in front of the class and raises his or her hand, this signals to the students to be quiet immediately” [p. 105]).

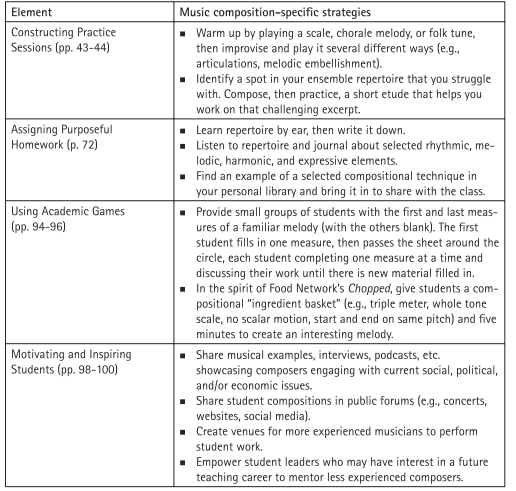

Figure 41.3. Composition-specific strategies for four elements (Onuscheck et al., 2020)

This framework could easily be expanded to provide teachers and evaluators with additional composition-specific strategies. Additionally, numerous visual art examples (where students creating original art seems more commonplace) in this text could be readily adapted. In Figure 41.3, I offer composition-specific strategies for four of Onuscheck et al.’s (2020) 43 elements.

Date added: 2025-04-23; views: 295;