Advancing Pedagogy through Program Evaluation

In this section, I will describe two program evaluation frameworks that could be adapted to my hypothetical scenario. I offer adaptation suggestions that could guide data collection to help evaluate our school’s instrumental music program with respect to music composition, and use findings formatively to make plans for subsequent academic years.

Then, I will describe and discuss two examples of recognitions—one from a state music education association and the other from a national professional organization— that lie somewhere between individuals’ informal assessments of a school music program and a rigorous program evaluation such as those described by Pennell (2020) and Wesolowski et al. (2019). I offer ideas for how music teachers and other stakeholders might encourage organizations to adapt their criteria to consider music composition an important element of their evaluative process.

Pennell. Pennell (2020) offers a model from PK-12 literacy education that is readily transferable to evaluating a K-12 music education curriculum. As in literacy education, where students develop a variety of skills (e.g., listening, speaking, reading, writing), music educators are tasked with facilitating student learning around diverse knowledge and skills associated with processes of creating, performing, responding, and connecting. Pennell frames this process in six overarching constructs: foundational skills, comprehension (K-3), comprehension (4-12), classroom literacies and independent reading, vocabulary, and writing. Pennell’s approach can evaluate an entire K-12 literary curriculum or one aspect of a curriculum.

While these overarching constructs are all relevant to music education (e.g., What are foundational skills for musicianship? What does it mean to comprehend music at K-3 and 4-12 levels? What musical vocabulary should a student develop?), I will focus here on Pennell’s (2020) chapter on the foundational skill of writing. The challenge of teaching students to write (in our case, compose) is not unique. Pennell summarized recent research indicating that “after third grade, very little instructional time is devoted to writing. Moreover, expectations for academic writing, both in and out of the classroom, remain scant. Given writing’s pragmatic purposes and cognitive super-power, this is an unfortunate reality” (p. 96). I will describe three elements of Pennell’s structures for evaluating writing and suggest how they might be applied to teaching composition.

Writing Framework. Pennell suggests districts adopt a writing framework, a non-negotiable that outlines “how educators will approach daily writing instruction and plan that instruction throughout the year” (p. 97). This plan might include daily allotment for writing, a yearlong calendar of genres to be covered, and tools for instructional design.

Whether my district chose to adopt such a framework, I could choose to audit my most recent year of teaching, keeping in mind my goals of (a) every student composing at least one piece each year, and (b) any school-organized public performance of a student group including at least one student composition. This evaluation may have revealed that in the previous year, I approached composition in my classroom through a composition unit beginning after the spring concert and state performance assessments. As I reflected, I realized that the timing of this unit made it impossible for students’ works to be played until the following year, and that students were feeling like the year was “over” after those concerts—motivation and positive momentum they felt through winter culminated in those performances.

Further, because students seemed to perceive this composition unit as disconnected from what happened in the rest of the school year, I found they were not making connections between concepts we worked on in preparing repertoire and their compositions. While time spent on phrasing, tonality, and tension and release while perfecting beautiful melodies in Vaughan Williams’s Folk Song Suite led to a musically satisfying performance last April, melodies in students’ compositions were awkward and felt mechanical.

Through this reflection, I realized that composition needed to be a more consistent presence in my classroom, and I decided to adopt a “composition framework” in my classroom. I might, for example, determine that: (a) I will spend 30 minutes of classroom time each week engaging students in composing; (b) I will focus on genres of imitative counterpoint, theme and variations, and electronic music (overlapping with plans for students to perform Frescobaldi’s Toccata, Chance’s Variations on a Korean Folk Song, and Shapiro’s Lights Out); and (c) use three existing books related to facilitating music composition (Freedman, 2013; Hickey, 2012; Randles & Stringham, 2013) and the Understanding by Design framework (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005, 2011, and 2015) as tools for instructional design.

Writing to Learn. Pennell describes Writing to Learn as “quick and meaningful writing tasks that promote critical interaction with a text or concept” (2020, p. 83) and distinct from Learning to Write, a process of prewriting, drafting, revising, and editing. This language literacy practice might be employed in disciplinary classes (e.g., an engineering notebook in science, an annotated bibliography of primary sources in history).

In my classroom, there are two approaches I could take to adapting this notion of Writing to Learn. I might use it in Pennell’s originally intended sense, helping students engage in developing language literacy. Students might contribute to a journal through a series of listening activities in which they respond to pieces based on Kaschub and Smith’s (2016) MUSTS and apply their contributions to creating their own compositions. I could also adapt this approach to writing music by developing a series of quick and meaningful composition tasks to promote interaction with a text or concept (e.g., Hickey’s (1997) SCAMPER toolbox) to develop a variation on a theme from Frescobaldi’s Toccata.

Digital Composition. Pennell suggests that given ubiquitous social media and digital tools, it is essential that students know how to create and consume digital texts. Pennell defines these texts as multi-modal, non-linear (e.g., hyperlinks on a web page), malleable (i.e., can be continuously edited), and shareable. These tools, Pennell suggests, should contribute a sense of purpose and authenticity around the writing process.

Musicians interact with a variety of digital tools in their work, and I might provide students opportunities to engage in digital composition using these tools. As a high school instrumental music teacher, I might engage my students in sampling their acoustic instrument and using it in a digital audio workstation project, facilitate a discussion about how composers share their music using digital tools (e.g., SoundCloud, TikTok, YouTube), or assign chamber groups to collaborate on their own arrangement of “Arirang” (the folk song in Chance’s Variations on a Korean Folksong) using Bandhub.

Wesolowski, McDaniel, and Powell. Wesolowski et al. (2019) offer an ecological approach to school music assessment as “a method for helping music teachers investigate the school, student, and community factors that affect their music programs and identifying the values associated with these factors” (p. 493). Their framework includes three spheres of influence: school (i.e., institutional values, standards and curricula), student (i.e., individual values, person-inenvironment), and community (i.e., local values, community attachment). Exploring these spheres could reveal relevant information for evaluating efforts to enhance composition pedagogy.

For example, teachers might discover a mismatch surrounding institutional values (e.g., standards, curriculum). State standards may call for students to engage in composing music, a district curriculum might conflate performing with creating and not explicitly indicate students should engage in composing music, and the building principal may be calling for a schoolwide emphasis on citizenship skills. This may highlight need for stakeholder conversations to align expectations and make curricular decisions based on these values; in this situation, I might plan to study repertoire with connections to citizenship (e.g., Ronald LoPresti’s Elegy for a Young American and Omar Thomas’s Of Our New Day Begun are both inspired by acts of violence against United States citizens by other United States citizens) and ground that year’s composition project in creating works examining United States immigration policies and citizenship.

Wesolowski et al. suggest that students’ individual values might be examined through five dimensions of human development (i.e., physical, affective, cognitive, spiritual, and social). How might students value creativity generally, and composition specifically, through these lenses? How might creating music afford students a platform to explore existential issues such as identity and purpose (spiritual)? How does hearing one’s original piece performed make a student feel (affective)? Do they find collaborative composition energizing or draining (social)? Better understanding how your students value composing and creating could provide valuable information to guide planning.

Community members’ values and perspectives are also important when considering a comprehensive evaluation of a school music program. Wesolowski et al. suggest exploring this through a three-dimensional model of (a) interpersonal relationships, (b) participation, and (c) sentiments. How do stakeholders interact in the process of advocating for and influencing individual students and the school music program at large (interpersonal relationships)? What are community members’ perceptions of ways in which they are directly and indirectly affected by the school music program (participation)? For example, a community member might be directly affected by engaging with the school music program by attending a concert; they might indirectly be affected by that concert attendance shaping their perceptions of specific music genres or practices. How do students feel about their local musical community (within and beyond the school) and their contributions to it (sentiment)?

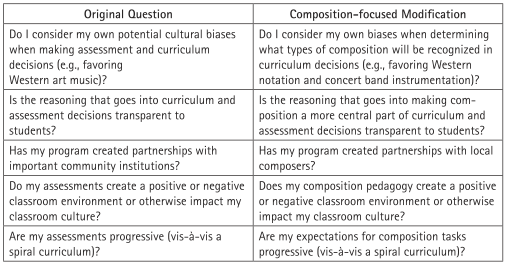

Figure 41.4. Composition-focused adaptations to the questions of Wesolowski et al. (2019)

Wesolowski et al. suggest that understanding institutional, student, and community value spheres can provide six streams of validity evidence to construct an ecologically valid school music assessment framework: (a) standards-aligned curricula and formal knowledge, (b) classroom democracy and student perceptions, (c) student self-efficacy and autodidactic knowledge, (d) local music and traditional knowledge, (e) locally and culturally appropriate teaching and ethnographic data, and (f) community service and community perceptions. The authors provide 60 questions that may be useful in facilitating data collection. Many could be readily adapted to a program evaluation initiative focused on composition, and could be used for self-reflection or to inform data collection. Wesolowski et al.’s original questions and composition-focused adaptations are listed in Figure 41.4.

Date added: 2025-04-23; views: 264;