The Pacific Ocean: Earth's Largest Ecosystem Explained

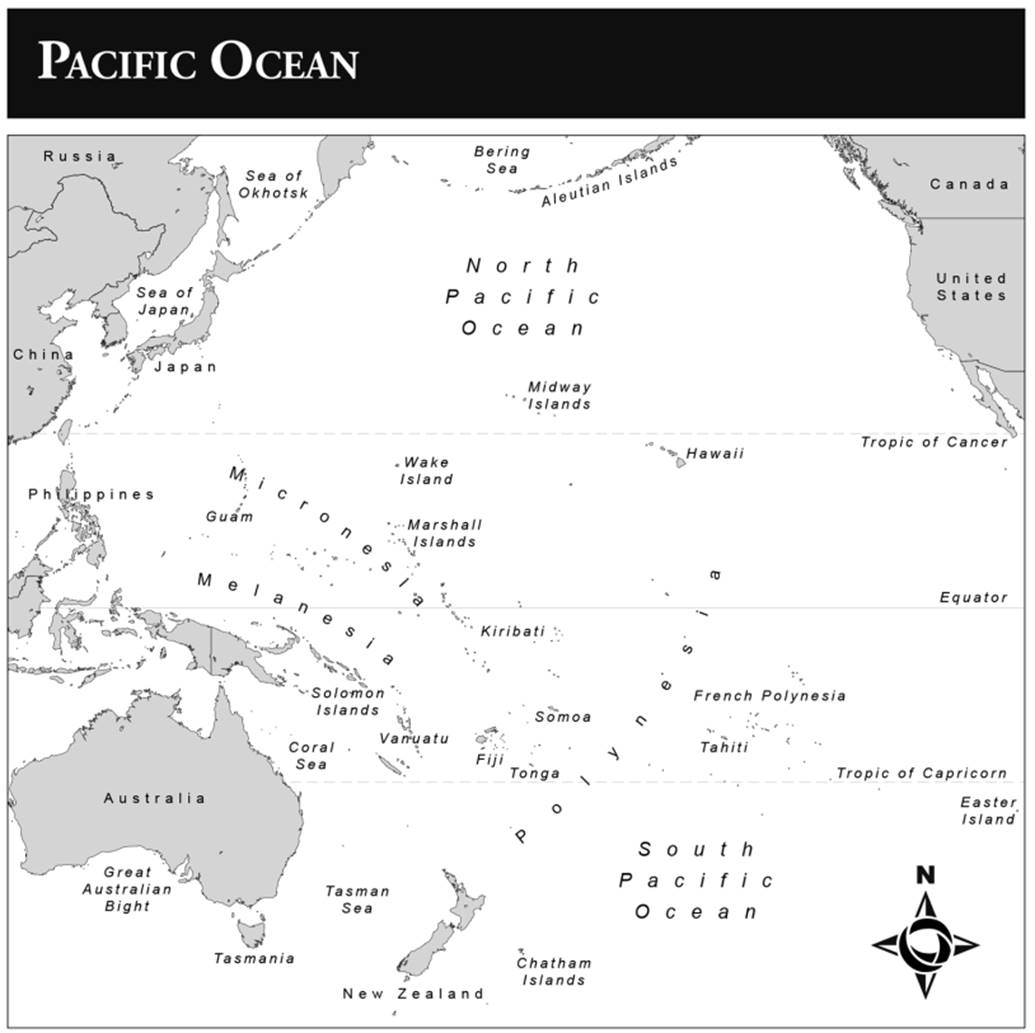

Introduction. The Pacific Ocean is the largest geographic feature on the Earth. Whereas the western and eastern boundaries of the Pacific Ocean are easily defined by the Pacific shores of Asia and the Americas, those to the north, south, and southeast are oceanic or insular, and the boundary becomes more arbitrary and fluid, being usually based on zones of most frequent human interaction. The Pacific is 10,400 miles wide at the equator and 9,200 miles separate Bering Strait in the north from Antarctica in the south. The rest of the world’s oceans would fit comfortably within the Pacific. The Pacific Ocean thus defined is larger than the combined area of all land on the Earth.

The notable lack of a coherent narrative on the Pacific’s history is largely the result of finding limited coherent or unifying narratives and themes that encompass its sheer size. The Pacific was, however, larger in the past and was indeed the first ocean. The fossil record and other geologic evidence, such as the distribution of rock types, suggest that twenty million years ago all of Earth’s landmass joined in one supercontinent known as Pangaea. This massive landmass was surrounded by a single great ocean, Panthalassa, which included the present-day Pacific Ocean. The other great oceans of today, the Atlantic, Indian, and Arctic, only came into being as Pangaea began to drift apart into its present configuration.

The marine environment of the Pacific Ocean consists of distinct local ecosystems linked by a series of deep-sea and near-shore currents, variable weather and climate conditions, and the movement of predatory species between distinct ecosystems in seasonal migrations to harvest periods of plentiful, locally concentrated biomass. Oceanographers now generally accept that all marine ecosystems are in constant flux and that they are open systems influenced by marine and climatic forces generated elsewhere. In tropical seas, concentrations of marine biomass are generally near the shore. Most marine species inhabit the benthic (ocean floor) or neritic (near-shore) zones rather than the pelagic (open ocean) zone. This distribution of marine biomass has been a major influence on human history in the Pacific Ocean.

Currents and marine migrations link many of these localized ecosystems. Deep cold- water currents flowing from colder latitudes are especially rich in nutrients and well up off the coast of California in the northeast Pacific and off Peru and Ecuador in the southeast Pacific. Warmer currents flow off the Pacific coasts of Japan and Australia, leading to diminished biomass in these waters, although in between lies the tropical Indo-Pacific region stretching from the South China Sea to the Solomon Islands, where warm, shallow seas promote rich biomass concentrations in coral and lagoon ecosystems in the area now- known as the coral reef triangle. Most of the marine species that inhabit the tropical Pacific originated here and spread eastward along tropical currents.

The Pacific has a particularly rich biomass, perhaps only rivaled by the Indo-Pacific coral reef triangle, although these cooler waters are also notable for the concentration of much of the biomass in higher tropic-level predators such as whales. Large apex predators link and shape local marine ecosystems. Whales reproduce in equatorial waters of low biomass, where there are fewer predators, but then migrate to feed on richer biomass concentrations in higher latitudes. Tuna, sharks, seals, and seabirds are similarly mobile to take advantage of seasonal and temporal variations in local biomass. Energy flows are also influenced by atmospheric exchanges such as winds.

The eastern two-thirds of the Pacific are divided into belts of winds blowing seasonally both eastward and westward, and the western third of the Pacific is dominated by monsoons and typhoons that can cause immense damage. The so-called El Nino Southern Oscillation (ENSO) weather pattern links weather from the Americas to Asia based on flows of air between different pressure gradients and exchanges between ocean and atmosphere in different parts of the Pacific that can cause drought or heavy rains for years in certain localities from Peru to India, and even into Africa.

The Pacific: A History Forged by Sea & Migration

How then to write a history of this vast ocean that is more than just passages of time between ports for the largely land-based history of humanity? Technologies to conquer and map distance figure in attempts thus far, and more recently environmental influences have been explored as linking themes. In 1994, historian John McNeill divided the history of the Pacific Islands into eras based on the type of technology that allowed the introduction of exotic flora and fauna into the islands and the pervasive economic approach to resource management.

The more efficient the transport technology, the more intrusive exotic elements became in islands relatively isolated for millennia from competing continental species. More recently, historian Ryan Jones has attempted to unify the past 500 years of the history of the Pacific through the concept of large-scale energy flows, both natural and anthropogenic, which span across the Pacific’s diverse local ecosystems and change over time. These energy flows include tsunamis, El Nino/La Nina (ENSO) climate cycles, whales, and human activities. Jones posits three historical periods based on energy flows. Until 1741, human colonization and use of the Pacific followed and exploited concentrations of energy flows in the form of fisheries.

In the following era of European colonial rule, colonial agents worked with indigenous peoples to harvest concentrations of energy flows, largely in the form of predators at the apex of marine ecosystems, beyond sustainable levels. After 1880, Jones argues that human activity added more energy into maritime ecosystems than it removed. Military activity, tourism, and economic development were largely responsible for these energy infusions, most of which remained near to shore.

The first colonizations of the diverse shores of the Asian and American Pacific Rims and the island worlds of modern-day Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands were remarkable achievements. These first colonizations took place over millennia, involving landscapes and seascapes very different from those of the modern Pacific. Later colonization eastward away from the first settled islands and continental coasts of the Pacific Rim involved feats of seafaring and navigation not reached by other seafaring cultures until thousands of years later. The ancestors of current Pacific Ocean populations encountered increasingly oceanic environments with lower ratios of land to sea, as well as less resourced island environments as they pushed farther out into the Pacific.

Oceania was first settled by Papuan-speaking peoples over 35,000 years ago. Their movement into the region was limited to New Guinea and some nearby Melanesian islands. During the last Ice Age, modern Siberia and Alaska were linked by a land bridge known as Beringia. This facilitated coast-hugging migration by boat from Asia to the Americas. The migrants could have skirted Beringia by this means until they reached the southern limit of the ice shield around the present-day Queen Charlotte Islands in modern-day British Columbia. About 11,000 years ago, rising temperatures signaled the end of the migratory opportunity as melting ice flooded low-lying areas of the land bridge, producing the Bering Strait, which was 45 nautical miles wide at its narrowest point.

After the Ice Age ended and sea levels rose with melting ice, the greatest maritime colonization of an oceanic environment in human history took place as Austronesian- speaking peoples from southern China colonized much of coastal Southeast Asia, crossed the Indian Ocean to Madagascar, and settled most of the Pacific Islands and discovered South America. These skilled seafarers and colonists began their diaspora 3,500 years ago. Their main route into the Pacific was down the eastern islands of Southeast Asia and then along the northern coast of New Guinea into Melanesia, and from there, north to Micronesia and east to Polynesia.

The islands of the Pacific become smaller and farther apart the farther east one goes. To populate the Eastern Pacific, Tahitians and their neighbors had to bring most of their food crops and domestic birds and animals with them to maintain their usual diet and supplement the food sources they found in their new homes. They also had to be exceptional guardians of their lands and seas because smaller island size and species poverty left little margin for mistakes compared to farther west in the Pacific. Most landscapes and near-shore seascapes in the Pacific Islands have been created directly or indirectly through human action.

Polynesian voyagers from Aotearoa/New Zealand even reached the sub-Antarctic Auckland Islands around 600 years ago, as witnessed by stone tools, shellfish, and the bones of nesting birds and seals. The amount found suggests a brief stay of a few years or more likely a few two-way seasonal trips in the summer months. DNA evidence has shown the pre-Columbian introduction of Polynesian chickens to Chile. The increasing evidence of contact with America now includes hard evidence for transportation in two directions. A Micronesian canoe has been found with Filipino coconuts on Mexico’s Pacific coast, although this may be no more than a one-off drift voyage or a discovery not followed up with two-way voyaging.

The sea remained central to the economies, interactions, and identities of the cultures of the archipelagos of South China, Southeast Asia, the Pacific Islands, and northwest Pacific coasts from colonization until the arrival of European imperialism. For example, the southeast coastal communities of China retained their maritime orientation well after the Austronesian diaspora from South America to Madagascar 3,000 years ago. Whereas imperial China was unified by political and military power based on the rich agricultural plains of the interior, the southeast resisted inland political powers until the 1500s, and well into the modern era remained a zone of piracy, smuggling, and other activities unsanctioned by the state.

The Japanese were the main culture to retreat from the sea and interact with outsiders in this period. Japanese maritime interests remained largely coastal and East Asian in orientation. Japanese and Okinawan seafarers, like their Chinese counterparts, were not easily contained by their central governments. Smuggling and piracy persisted to the point where Chinese authorities felt their lawless coasts were destabilizing effective government. Japanese wako (pirates) raided the coasts of China, Korea, and Japan from outlying islands of the Japanese archipelago. In the sixteenth century, multinational groups of East Asian seafarers, never beholden to authority, fended off Japanese, Chinese, and later Dutch attempts to control them and developed Formosa (Taiwan) and the Fukien coasts as their independent base of operations under Koxinga. Farther south, in archipelagic Southeast Asia, relatively low population density and relative abundance of land separated polities geographically and provided many mangrove-clad shores beyond the reach of state control from where seafaring peoples ventured forth to attack trading vessels and capture slaves.

Although archaeological analysis generally perceives a diminishing of seafaring over time in the Pacific Islands, historians are less sure. Long voyages between archipelagos are recorded in traditions into the late eighteenth century. Even after sustained European contact after 1770, regular voyaging occurred in eastern Polynesia centered on Tahiti; between Tonga, Samoa, and Fiji in western Polynesia; and between the coral islands of the Western Caroline Islands and their high-island neighbors in Micronesia. Historians Neil Gunson and Mark Berg, archaeologist Janet Davidson, and linguist Paul Geraghty have shown the exchange to be long-standing, dating back probably at least 1,000 years before they were observed by Europeans in the nineteenth century.

There are indications of a Pacific maritime trade network between southern Ecuador, on the one hand, and Guatemala and Mexico, on the other. This assessment is based on similar cultural traits such as burial practices, ceramic styles and motifs, and metallurgy in the two areas that are separated by 1,800 nautical miles of coasts largely devoid of these traits. These similarities between cultural traits in these two areas started as early as 3500 to 4000 BP, and were still present when European contact occurred in the sixteenth century. In Ecuador and parts of Peru, balsas, large rafts of bound balsa logs, served as the primary maritime vessels that were capable of such passages.

Date added: 2025-08-31; views: 270;