How Technology Opened The Pacific To European Expansion

The second great maritime expansion into the Pacific arose from revolutions in European military and nautical technology, and enhanced state power combined to enable a number of European states to send cannon-armed European vessels across the North Atlantic to the Americas and down the Atlantic coast of Africa into the Indian Ocean. From there, the Spanish moved into the Pacific from the Americas and the Portuguese from Southeast Asia.

Distance from home, limited resources at this frontier of an already overextended empire, navigational imprecision in the open ocean, and the tenacity of Southeast Asian and East Asian sea cultures’ resistance combined to limit their conquest of Pacific peoples and sea spaces. Dutch, English, and French expeditions followed, but largely focused on their European rivals. Pacific spaces were not systematically and precisely mapped and explored until the three great voyages of Captain James Cook from the late 1760s until his death in Hawai‘i in 1779, when the newly perfected chronometer revolutionized European navigation.

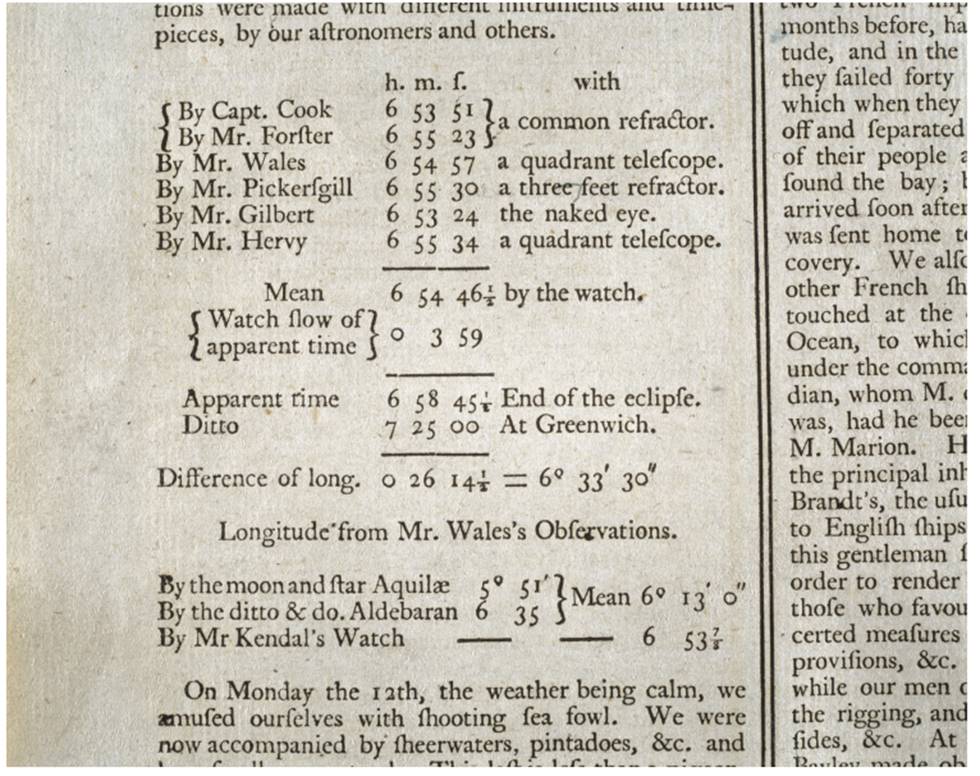

Lunar eclipse observations taken during the second Pacific voyage of Captain James Cook, 1772-5 (SSPL/Getty Images)

European encounters with the South Pacific began in 1520 when Magellan sailed westward across Oceania from South America. Other Spanish voyages of discovery followed in his wake. A series of violent encounters and the decimation of colonies in Melanesia from malaria soon ended Spain’s South Pacific engagement. Henceforth, the Spanish focused on Micronesia and the trans-Pacific galleon trade carrying goods between the colonial ports of Manila and Acapulco. Their route bypassed most inhabited islands in the Pacific, and former links between Guam and the Caroline Islands diminished with the violent establishment of Spanish rule in the Marianas and the subsequent loss of seafaring capacity within the island chain. The Portuguese fared little better than the Spanish in eastern Southeast Asia, with their limited numbers making them more petty rivals than conquerors to the thriving maritime states they came up against.

The Spanish and Portuguese ability to discover and plot Pacific coasts was limited. Their vessels were often smaller and less seaworthy than those of the Austronesian inhabitants they encountered. Although the sextant allowed them to determine their latitude by measuring the distance of the sun from the horizon at noon, their ability to plot and record their passages was restricted by not having a precise way of measuring locations along any east-to-west axis. Shipworms (teredo) riddled their vessels and left many in a virtual state of collapse, while the poor diet on a ship meant that scurvy ravaged all crews, debilitating the majority before any trans-Pacific voyage could be completed. The same held true for English and Dutch vessels that followed until a series of naval revolutions occurred in the 1770s under the supervision of master mariner, Captain James Cook.

Cook was able to use the new chronometer invented by John Harrison to accurately measure time and therefore map positions on an east-to-west axis (longitude) in the Pacific. This enabled his expeditions to precisely plot longitude for the first time in history after the estimation of latitude had been resolved during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries by measuring the altitude of the sun at noon against a table plotting the sun’s declination on any given day in European navigation. The intersection of the north-to-south position (latitude) and longitude provided a precise and accurate measure of position. Cook’s drive and determination to explore and map as much as he could and his superb seamanship resulted in vast areas of the Pacific being mapped before he was slain in Hawai‘i in 1779 by indigenous peoples.

The other great seafaring problem Cook resolved was scurvy, which would hit crews about six weeks into voyages fed on the standard but nutritionally insufficient diet of salted rations. Scurvy was a main cause of high death rates on vessels until this time. Although the general dietary remedy for scurvy had been suspected prior to Cook’s voyages, it was his disciplined enforcement of suspected dietary cures containing unpopular-tasting elements that at last considerably reduced the ravages of scurvy.

European contact with the Pacific became more sustained after Cook’s maps and journals opened up the Pacific world to European audiences. New ideas and experiences, goods, and pathogens were the most significant influences on indigenous cultures during the first century of sustained Western contact. Introduced diseases are generally regarded as the most devastating influence of sustained Western contact on Oceanic societies. Millennia of voyages out into the Pacific separated islanders from their Asian roots and the diseases that periodically ravaged Eurasia. Seaborne colonization effectively filtered out many health problems that were endemic to those who remained behind.

The journey by voyaging canoes provided time for the diminution of any diseases that may have existed at the beginning of the journey. Only the healthy were chosen for colonizing expeditions, and the farther one moved out into the Pacific, the greater the distances and traveling times between islands. Voyages became progressively more difficult and extensive, with increasingly less possibility for the persistence of acute infections. Furthermore, the initial populations of the islands were small and scattered so that the conditions required for the establishment of endemic infectious diseases did not arise. The establishment of infectious disease requires a critical mass of people, wherein the number of new infections is balanced by the birth of new susceptible, nonimmune members of the community. Such a critical population density was not present in the islands.

A number of works have explored the unsustainable commercial extraction of flora and fauna by Europeans—sandalwood, beche-de-mer, whale oil, and pearl shell, particularly whaling and sandalwood. These industries left a limited human footprint on the land or sea beyond species depletion, as none required major permanent settlements or infrastructure. Dorothy Shineberg’s publications on the sandalwood trade remain models of scholarship on resource extraction and its cultural and ecological implications, despite being published over forty years ago. Her work demonstrates that the trade was mutually beneficial and Pacific Islanders were astute and skilled traders. A greater impact occurred in marine ecosystems, however. Even before Cook arrived, the Russians were busy harvesting the wealth of fur seal, sea lion, and sea otter pelts along the northwest coasts of the Pacific that fetched a high price in the markets of China and, to a much lesser extent, Europe. Soon, English, American, and French traders joined them in seeking fur seal and sea otter pelts for the Canton market. Local sea peoples skilled in hunting these creatures, such as the Tlingits, Haida, and Aleuts, participated in this trade either as employees or through coercion.

Even before fur seal and sea otter numbers had plummeted along the temperate and subpolar shores of the Pacific, the scale of whale hunting dwarfed the fur trade. From the 1790s until the 1860s, whaling vessels manned by multinational crews hunted whales across the whole Pacific except the forbidding and stormy seas of Antarctica. Whales were hunted for the oil their bodies contained to fuel the industrializing Western world with lighting oil and industrial lubricants. Whale blubber was not seen as a prized source of food by Westerners as it was for indigenous Pacific whaling cultures. Whaling vessels out of New England on the Northeast Atlantic coast of the United States rose to dominate the industry. It is perhaps not surprising that the first whaling grounds to be exploited in the 1790s were in the southeast Pacific off the coasts of Chile and Peru, just after the passage from the Atlantic around Cape Horn. Thereafter, the whaling frontier moved essentially farther and farther west and north. Many, if not most, voyages would see ships roam across the Pacific from South America to Japan seeking abundant hunting grounds, with the range increasing as whale numbers diminished. Crews were multinational and multicultural, including large numbers of Pacific Islanders.

Date added: 2025-08-31; views: 233;