The Global Overfishing Crisis: Threats to Marine Ecosystems and Food Security

Unsustainable harvest is perhaps the most serious threat to marine environments worldwide. Overharvesting is not a new phenomenon in the oceans. Many traditional cultures either removed the available species and moved on to harvesting other areas or had to develop methods of regulating the timing and amount of harvest in order to avoid overexploitation. With the advent of the Industrial Revolution came the increasing mechanization of fish harvesting. Species such as large whales and previously difficult- to-catch offshore pelagic—living in an ocean area that is neither near the shore nor the bottom of the sea—fish became accessible in a common environment owned by no one. Most whale species have been reduced to levels where they are considered endangered or threatened. Most populations of palatable fish stocks have been seriously depleted.

The importance of marine fisheries is often overlooked. From a Western perspective, seafood is simply another source of protein for consumers to choose. However, currently, over one billion people depend on seafood as their primary source of protein, and three billion people rely on seafood for at least 15 percent of their protein. Fishing has recently been estimated to employ thirty-four million people in full- or part-time jobs, producing eighty million tons of seafood in 2009. The first-sale value of the world’s fisheries is estimated at $ US 100 billion.

Be that as it may, the sustainability of marine capture fisheries has recently been shown to be at risk. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) currently reports that 30 percent of the world’s fisheries are now overexploited, depleted, or recovering. Indeed, 57.4 percent are fully exploited and only 20 percent underexploited or moderately exploited. Global catches peaked in 1996 and, for the past fifteen years, have been relatively stable at a level approximately 10 percent less than that in 1996. For context, in 1974, the corresponding percentages were 10, 50, and 40, respectively. The Commission of the European Communities has determined that, for the European fish stocks where stock status is known, only a third are currently managed for sustained future production. In the United States, 63 percent of the 105 managed fish stocks are either overfished or currently being overfished. In New Zealand, 29 percent of the 101 stocks or stock complexes in which status can be determined are below their management targets.

The status of high-seas stocks is even less well-known. Of the seventeen Atlantic fish stocks managed under the North Atlantic Fisheries Organization, six have collapsed and only three are considered sustainable. Atlantic cod biomass is estimated at 6 percent of historical levels, and North Sea cod stocks are depressed to such a degree that for years fishers have been unable to harvest up to their allowable catches.

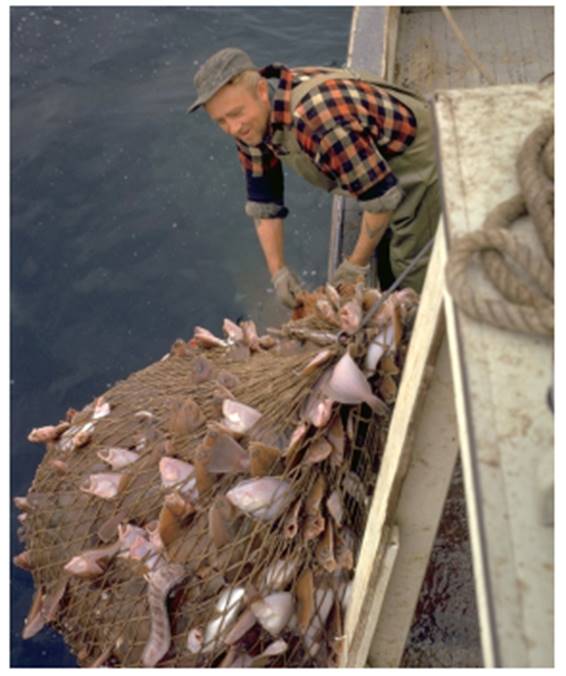

Fishermen hauling trawl nets filled with cod. Atlantic cod biomass is estimated at 6 percent of historical levels and North Sea cod stocks are significantly depressed as well (Corel)

The following regions contribute the largest proportions of the global catch:

- Northwest Pacific (25 percent)

- Southeast Pacific (16 percent)

- Western Central Pacific (14 percent)

- Northeast Atlantic (11 percent)

- Eastern Indian Ocean (7 percent)

A closer look at certain aspects of marine capture fisheries shows that 50 to 70 percent of pelagic predators (i.e., tunas, swordfish) have been removed by fishing. Fishing pressure continues to shift toward lower trophic levels as apex predators decline; this has been termed “fishing down food webs.” Furthermore, the global fishing fleet is far larger than what necessity dictates, especially because technological innovations increase the ability to catch fish. This surplus fishing capacity is underwritten by $US 30 to 40 billion in annual subsidies by most fishing nations, thus providing no incentive to reduce fishing efforts. In addition, evidence suggests that fishing efforts from port-based fisheries have increased over the past three decades at upward of 3 percent per decade. As such, more fishers are chasing fewer fish, and if one were to imagine the global fishing fleet as a country, it would be the eighteenth largest oil-consuming nation on Earth.

Another serious problem is the unintended harvest of species. An estimated 20 percent of the global fisheries catch constitutes an unwanted bycatch that is discarded. Shrimp fisheries produce the largest bycatch and small pelagic fisheries the least. Bycatch also consists of the incidental take of endangered marine mammals, turtles, and seabirds, although recent advances in gear technology are reducing these impacts. Lastly, approximately 35 percent of the global annual catch is captured on nontropical continental shelves, which occupy only 5 percent of the total ocean area. In order to sustain these fisheries, it is estimated that current harvest levels on nontropical continental shelves require 36 percent of their total primary productivity.

There was little perceived need for fisheries management prior to the twentieth century. Marine fisheries (including marine mammals) were thought to be inexhaustible, so there was little impetus to allocate resources toward their management. Most fisheries (including nearshore ones) were “common” resources, which were open to anyone with the equipment to exploit them. With the advent of the internal combustion engine, fisheries easily accessible from land were quickly depleted and the need for management was realized. A suite of national and international legislation and conventions was developed to enforce fisheries regulations. These included the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling (1946) and the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (1958). A number of other conventions, including MARPOL (1973/8), the London Dumping Convention (1972), and the Convention for the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter (1993), were designed to protect marine environments—and therefore fisheries—from land- and marine-based pollutants.

It is estimated that commercial fishermen catch an estimated fifty million sharks as bycatch. Novel methods to reduce such alarming numbers have been hampered by the increase in demand for shark fin (Andreas Altenburger/Dreamstime.com)

Fisheries employ a variety of techniques that can be categorized in a number of ways; however, four types of fisheries are generally recognized: food, industrial, shellfish, and recreational. Food fisheries are operated by and for local peoples, and although declining over the past thirty years, fisheries continue to be vital to both developed and developing nations. Food fisheries generally harvest near-shore finfish and shellfish, with some remaining subsistence whaling by indigenous peoples in Arctic areas. Industrial fisheries have been the fastest growing in recent decades due to improvements in vessels, fishing gear, and technology (e.g., satellite images, global positioning systems). Industrial fisheries are the dominant harvesters on the high seas and are increasingly harvesting pelagic invertebrates (e.g., squid, krill). Shellfish fisheries, on the other hand, target invertebrates that are primarily on or within the benthos. Finally, recreational fisheries operate throughout the world, and there are limited statistics on the total amount of such landings.

Date added: 2025-10-14; views: 176;