Vasco da Gama and the Sea Route to India: How Portugal Forged a Maritime Empire

Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama’s three voyages between 1497 and 1524 opened an ocean route for trade between Europe and Asia. His 1497-9 voyage represented the first major European incursion into the Indian Ocean. It also culminated fifty years of Portuguese expansion along the west coast of Africa. Ever since the Portuguese conquest of Ceuta in 1415, navigators of this nation ventured out into the Atlantic. Over the next seventy-five years, Portuguese voyagers encountered the islands of the Azores and Madeira and slowly coasted down the coast of West Africa. The 1488 rounding of southern Africa by Bartolomeu Dias proved conclusively that the Indian Ocean could be reached. Da Gama’s 1497 expedition represented the culmination of these efforts. His expedition gained more prominence through Columbus’s voyages to the Americas and a treaty that the Crowns of Portugal and Spain had signed at Tordesillas (1494), dividing the Atlantic Ocean into two respective spheres.

Little is known about Vasco da Gama’s early life. He was the third son of Estevao da Gama, a nobleman from Alentejo, a town in southwestern Portugal. His exact date of birth is controversial, with some historians citing the year 1460, whereas others prefer the year 1469. Da Gama’s status as a minor nobleman in Portugal led him to seek fortune overseas. He distinguished himself in command against a French fleet in 1492, and three years later King Manuel of Portugal chose da Gama to lead four ships to the rich town of Calicut in India. At the western end of Europe and without direct access to the Mediterranean Sea, Portugal bristled at the price of pepper, cinnamon, nutmeg, and other spices after they had changed hands several times, with an increase in price at each exchange, along the land route west from China and India. Although Da Gama’s name is associated with this expedition, much credit should also go to Pero de Alenquer, the experienced pilot of the expedition. Before joining da Gama, Alenquer had guided the important voyages of Diogo Cao and Bartolemeu Dias.

At this juncture, background is helpful. Since antiquity, intellectuals, following the ideas of astronomer and geographer Claudius Ptolemy of Alexandria, Egypt, believed that Africa had no southern tip. Rather, it curved from north to south and back north on the other side of the globe. That is, no waterborne route existed to take one from the western edge of Europe to Asia. Dias’s voyage in 1488 went from southwestern Africa around the southern tip of Africa to southeastern Africa. Dias’s voyage laid the foundation for da Gama’s successes.

In 1497, da Gama set sail, again down the western coast of Africa. Only five years had elapsed since Columbus’s first voyage, and there remained much uncertainty about what he had accomplished. Da Gama also had no accurate map of the eastern (Swahili) coast of Africa. He made contact with the important Swahili trade cities of Mozambique, Mombasa, and Melindi. It was in this last city that da Gama succeeded in locating a pilot to take them across to India. Historians have long maintained that this pilot was Ahmed ibn Majid, but it was most likely one of his students. Relying on the expertise of this Arab pilot, da Gama reached Calicut, India, on May 22, 1498. Relationships with the local rulers soon soured, and da Gama, after loading some spices, departed to return to Portugal. The voyage back fell outside the important monsoon wind exchange, and his crew fell ill and some died. One ship had to be abandoned due to lack of manpower. He finally arrived in Lisbon in September 1499 to much acclaim. Da Gama would undertake two more expeditions to India, one in 1502 and his final voyage, as viceroy of Goa, in 1524. Reaching Cochin, da Gama died on Christmas Day 1524. Only in 1538 was his body returned to Portugal for burial.

Legacy.By the time of da Gama’s death Portugal had established ports in Asia from Diu on the western tip of India to Melaka near the southern tip of Malaysia, providing the Portuguese with a window of opportunity in the rich Indian Ocean trade. Although Portugal never controlled the whole of the Indian Ocean, Lisbon captured half of the spice trade between Europe and Asia. The wealth returned from the Indian Ocean enabled Portugal to develop a vast maritime empire that stretched from Asia to Africa and from there to Brazil in South America. Although contested by local rulers as well as other European nations, remnants of this empire continued to exist until the late twentieth century. Christopher Cumo and Rainer F. Buschmann

FURTHER READING:Cuyvers, L. 1999. Into the Rising Sun: Vasco da Gama and the Search for the Sea Route to the East. New York: TV Books.

Kratoville, B. L. 2001. Vasco da Gama. Novato, CA: High Noon Press.

Stefoff, R. 1993. Vasco da Gama and the Portuguese Explorers. New York: Chelsea House Publishers.

Deep-Sea Exploration: History & Technology of Unlocking the Ocean's Mysteries

Deep-sea exploration can be defined as studies of the physical, chemical, and biological properties of marine environments too deep for divers to access unassisted. The deep sea is the most challenging environment to research and explore on Earth. Photosynthetic activity disappears after 100 meters, and below the mesopelagic zone (800 to 1,000 meters), it is perpetually dark and cold. The average sea-floor depth is 3,688 meters, with an increasing pressure of one atmosphere every 10 meters. Marine trenches can extend much deeper; the Marianas Trench reaches 10,900 meters depth in the Challenger Deep segment. This segment is 2,000 meters farther from sea level than the peak of Mt. Everest. Twelve persons have been to the moon, only three to the bottom of Challenger Deep. Scientists have mapped more of the surface of the moon than the sea floor. Nonetheless, many technological advances made in the last two centuries have greatly expanded our knowledge of this rich, mysterious environment.

The earliest measurements of deep-sea depths were done with bathymetric sounding equipment lowered from ships. The first recorded soundings were by Vikings in 700 to 800 CE; they used ropes or wires with heavy weights attached and lowered over the side. Their readings could be very inaccurate due to line drift caused by currents and ship movement, and left no way of knowing precisely when a weight had reached the seabed. In the late 1700s, the French scientist Pierre Simon de Laplace (1749-1827) calculated the depth of the Atlantic Ocean at approximately 4,000 meters by observing tidal motion in Brazil and Africa, an impressively accurate figure compared to empirically measured readings over the next century.

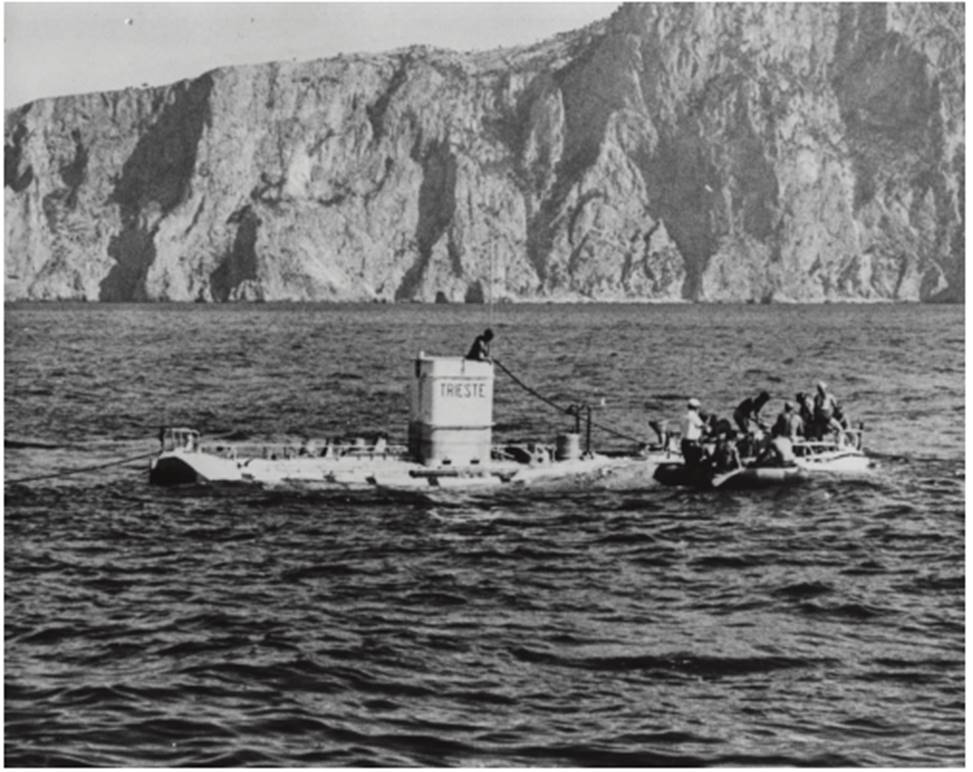

The US Navy’s bathysphere Trieste on its way to take part in the search for a sunken nuclear submarine in 1963 (Bettmann/Getty Images)

Deep-sea exploration began in earnest in the 1800s when interest in oceanography grew as governments began to improve shipping lanes and intercontinental commerce, lay communication cables, and build and operate early submarines. The biology of the deep sea was still largely unknown when British naturalist Edward Forbes, after fruitless voyages in the Aegean, proposed his Azoic Theory in 1843—that below 300 fathoms (550 meters) the ocean would be nearly or completely devoid of life. Despite contemporaneous contrary evidence, this theory was widely accepted for nearly twenty years until transatlantic cables pulled up encrusted corals and other life from deeper than a mile.

Comparing the Ocean and Outer Space. In many ways, large parts of the universe surrounding Earth are better known than the bottom of the ocean. For instance, with roughly 5 percent of the ocean floor mapped accurately, compared to 87 percent of the planet Mars, we now have more thorough maps of Mars than we have of the oceans’ deep. Likewise, more people have been to the moon—a total of twelve individuals—than to the Challenger Deep. Only three people have been to the Challenger Deep, which is located in the Mariana Trench and is the deepest known point of the world’s oceans. Christopher MacMahon

The first modern oceanographic research expedition took place from 1872 to 1876 on the British corvette HMS Challenger under the direction of the naturalist Sir Charles Wyville Thomson (1830-82). On the 127,580-kilometer journey, the crew took nearly 500 deep- sea soundings and 133 bottom dredges. They described 4,700 new species of marine life in a fifty-volume publication that took twenty years to complete. Using advances in depthsounding methods, the expedition also discovered undersea mountain chains, including what we now know as the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, and trenches including the previously mentioned Marianas Trench—for which the Challenger Deep is named. Engineering innovations on this cruise led to many deep-sea sampling techniques, including dredges, trawls, and sounding equipment that are still used today. Additionally, the Challenger expedition opened the gate to a number of important oceanographic expeditions in the late 1800s and early 1900s, primarily led by the United States and Britain.

The First World War led to a number of advances in oceanic acoustic research as governments devised methods to detect enemy submarines. Acoustic soundings were used to better describe and map sea-floor features, creating the first ocean-wide maps. Advances in radar later in the twentieth century, accelerated by the Second World War, led to the discovery of more detailed sea-floor features, as well as the biological phenomenon known as the deep-scattering layer. The deep-scattering layer is a diel migration of fish and other marine organisms that are found at 300 to 500 meters each day and come to the surface to feed at night.

Deep-sea exploration in the latter half of the twentieth century was dominated by advances in human-occupied submarines and remote-operated/autonomous underwater vehicles (ROVs/AUVs), including the most famous research submersible, the DSV Alvin, operated by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, launched in 1964 and rebuilt in 2014. These vessels allow scientists to directly interact with the deep-sea environment and have led to many important discoveries, such as undersea volcanoes, hydrothermal vents, and the final resting place of the Titanic. Two manned vessels have actually reached the bottom of the Challenger Deep: the Trieste in 1960 with Jacques Piccard and Don Walsh, and the Deepsea Challenger, which carried filmmaker James Cameron in 2012. Geoff Dilly

FURTHER READING:Gallo, Natalya D., James Cameron, Kevin Hardy, Patricia Fryer, Douglas H. Bartlett, and Lisa A. Levin. 2015. “Submersible-and Lander-Observed Community Patterns in the Mariana and New Britain Trenches: Influence of Productivity and Depth on Epibenthic and Scavenging Communities.” Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers 99: 119-33.

Johnson, Martin W 1948. “Sound as a Tool in Marine Ecology, from Data on Biological Noises and the Deep Scattering Layer.” Journal of Marine Research 7 (3): 443-58.

Kaharl, Victoria A. 1990. Water Baby: The Story of Alvin. New York: Oxford University Press.

Murray, John. 1895. A Summary of the Scientific Results Obtained at the Sounding, Dredging and Trawling Stations of HMS Challenger, Vol. 1. London: HM Stationery Office.

Date added: 2025-10-14; views: 266;