El Nino and La Nina Explained: A Guide to the ENSO Weather Patterns

El Nino and La Nina are opposing weather patterns that originate around the equator in the central to eastern Pacific Ocean. Climate scientists have named these weather patterns the El Nino Southern Oscillation (ENSO). From the outset, care must be exercised in the use of terms. Weather and climate are not synonymous. Weather and climate both include a number of phenomena: temperature, rainfall, snow, the amount of sunshine, and other factors. Note, however, that weather involves the short-term tracking of these phenomena and so will inherently fluctuate. We intuitively experience this fact. On any given day, it may be 75° F, and the next day the temperature may drop to 52° F. Such fluctuations are particularly noticeable in spring and autumn in the temperate zones.

Climate, on the other hand, is weather measured over the long term, millennia in many cases. Long-term patterns even out the day-to-day fluctuations of weather. By taking the long view, one may note changes in climate over very long durations. For example, during the Cretaceous Period and the era of the dinosaurs, the climate was warmer than it is now. However, some 20,000 years ago, Earth was in the grips of an Ice Age that made life difficult in the temperate zones. Over the last 12,000 years or so, the climate has moderated and been comparatively stable. This period is known as the Holocene and has coincided with the rise of humans as the dominant member of the biota.

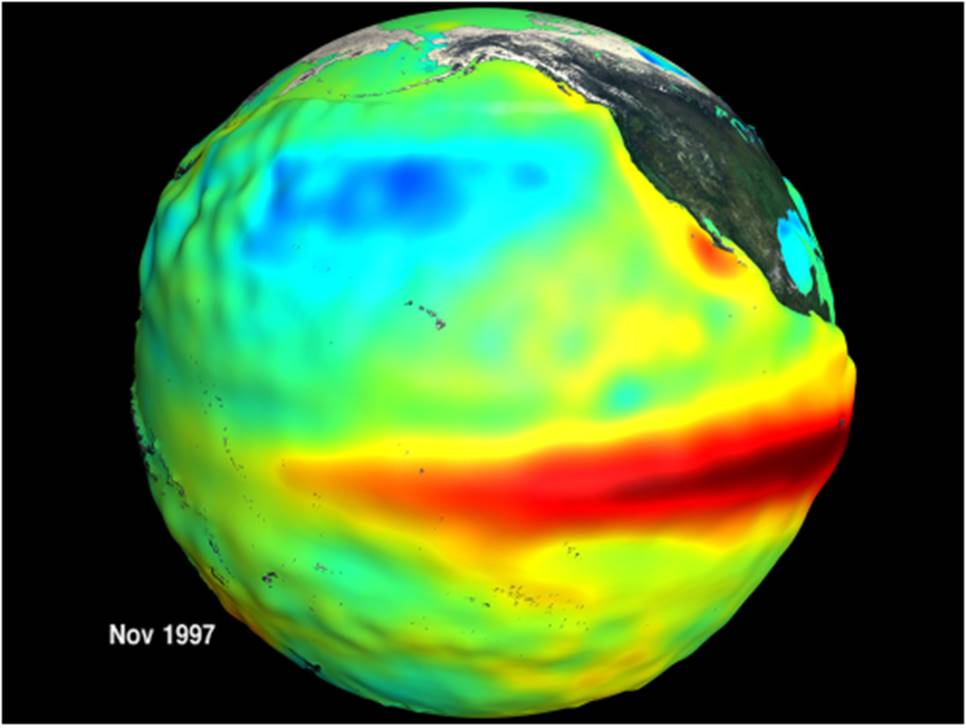

Image created by NASA to depict the sea surface anomalies occurring during El Nino. The dark band seen near the equator indicates warmer-than-normal temperatures (NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center Scientific Visualization Studio)

El Nino. El Nino is the warming effect in the equatorial Pacific. The Spanish phrase El Nino literally means little boy. The phrase is commonly used to refer to Jesus’ as a baby and infant, a time of presumed innocence. The name seems surprising given that El Nino is not a small or inconsequential event. As early as the seventeenth century fishermen on the western coast of South America detected the warming trend of El Nino but could not pinpoint the cause. Because these fishermen noticed the warming trend around December, they named it to coincide with Jesus’ putative birth on December 25.

El Nino works by hastening the movement of warm equatorial waters in the Eastern Pacific Ocean to both South and North America. Note that the equator runs through South America, but that North America, particularly the United States and Canada, is well north of the equator. Nevertheless, the effects of El Nino radiate well north of the equator and warm the subsequent year for people in the temperate zone of North America. The winter of 2015 and 2016 provides a good example of an El Nino effect. Consider Ohio in the United States, a state ensconced in the temperate zone. Snowfall that winter fell markedly below the levels of the last several years. Ski resorts were desperate to produce sufficient snow in this environment. Even cold spells seldom plunged the temperature below 20° F. In sum, the winter was mild when compared to other episodes. At this writing, it is premature to speculate about the summer, but there is no reason to expect it to be cool.

La Nina. La Nina, as mentioned earlier, is a weather phenomenon that opposes El Nino. If El Nino is the little boy, La Nina is the little girl. The use of gender in these labels seems surprising because weather cannot be postulated in such terms. Only the attempt to personify weather prompts people to extend the jargon of gender to natural forces. We see this phenomenon today when meteorologists name tropical storms and hurricanes. At first the practice included the exclusive use of male names, but now these events may be named after Helen, Lisa, or some other female first name.

La Nina is a fascinating weather pattern that involves the movement of the warmest equatorial waters west and away from South America, just as El Nino had pushed these waters east and toward South America. In the case of La Nina, the movement of the warmest waters west leaves only cooler waters near South America. The result is cooler weather for roughly the next year in the American tropics, subtropics, and temperate zones. One should take caution against exaggerating these effects. During La Nina, it is never cold enough for snow to fall in the tropics. The subtropics may be a different matter. In some La Nina years, frost affected citrus trees in south Florida. Because no citrus tree can tolerate a hard frost, such events have cost growers millions of dollars in losses and the need to replant acreage. In such cases, La Nina has the power to disrupt the economy, or at least an important sector of it.

Yet La Nina patterns are not entirely uniform. In the southeastern United States, winters may actually warm during an episode. In the southeast, then, La Nina and El Nino may produce indistinguishable results—that is, weather warms in both instances. Episodes in the southeast should not detract from the overall cooling that La Nina produces. Both La Nina and El Nino modify the location of warm equatorial waters in the Pacific Ocean and so gain strength from their origin as tropical events. Christopher Cumo

FURTHER READING:Aguado, Edward and James E. Burt. 2013. Understanding Weather and Climate. Boston: Pearson. Philander, S. George. 1990. El Nino, La Nina, and the Southern Oscillation. San Diego: Academic Press.

Romm, Joseph. 2016. Climate Change: What Everyone Needs to Know. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Shonk, Jon. 2013. Introducing Meteorology: A Guide to Weather. Edinburgh: Dunedin.

Date added: 2025-10-14; views: 269;