Magellan’s Circumnavigation: Redrawing the World Map

The Portuguese sailor Ferdinand Magellan (Port. Fernao de Magalhaes) led the first recorded circumnavigation of the Earth between the years 1519 and 1522. Although he was killed before the conclusion of the voyage, his mission led to a rethinking of European geographical perceptions of the world. Magellan’s circumnavigation was the first empirical proof of the Earth’s roundness, and it disproved the notion that seas and oceans were landlocked—as derived from the Greek geographer Ptolemy—and showed that the Americas were not necessarily a barrier between Europe and Asia. Rather, merchants could sail from one continent to the other by passing through a strait Magellan discovered and named at the southern tip of South America.

EARLY LIFE. Born about 1480 in either Sabrosa or Porto, Portugal, Ferdinand Magellan was the son of Rui de Magalhaes and Alda da Masquita, both nobles. Queen Leonor of Portugal brought Magellan as a boy to Lisbon, where he served as her page. He joined the Portuguese fleet in 1505 and sailed to the Indian Ocean, a region of the world under Portuguese control. He was present in the Portuguese capture of the strategic port of Melaka in Southeast Asia in 1511. He remained in the Indian Ocean until 1512. Wounded in one battle and decorated for valor in another, Magellan made his mark. His willingness to fight alongside his men made him a trusted leader. Magellan rose to the rank of captain in 1512, and he returned briefly to Lisbon. The next year he was wounded again in a battle against Muslim Arabs in the Mediterranean Sea. Despite Magellan’s wounds and heroism, King Manuel of Portugal refused twice to increase his pay, suspecting that Magellan had illegally authorized trade with the Muslims. Magellan denied the charge, and in 1517 pledged loyalty to Spain, Portugal’s rival.

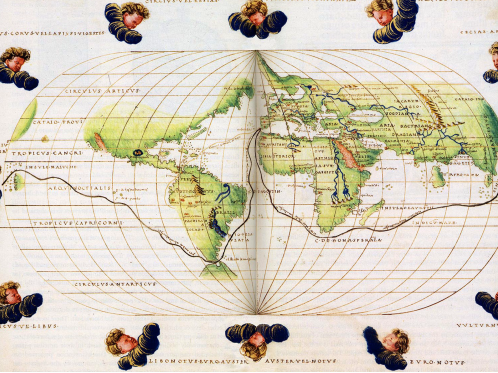

A map of Magellan’s route from a portolan atlas by Battista Agnese, c. 1544. In addition to Magellan’s route of circumnavigation, the map reflects the extent of European knowledge of world geography within fifty years of Columbus’s 1492 arrival in the Caribbean (Library of Congress).

THE MARITIME CONTEXT. Spain and Portugal had long been rivals on the Iberian Peninsula. This rivalry had spilled over into the Mediterranean Sea, and by the time both powers established a maritime presence, it had become a global phenomenon. Both Catholic countries, each thought that God had destined it for world domination. The rivalry was especially sharp in economic affairs. Both nations desired to circumvent the overland trade route from China and India to the eastern edge of the Mediterranean Sea. The problem was that as goods changed hands from merchant to merchant, prices of goods, especially spices, increased. Moreover, it was obvious that Muslim and Jewish middlemen were profiting at the expense of Portugal and Spain. These Catholic nations pursued the same goal by different paths. The Portuguese went east around the southern tip of Africa to reach India and the rest of South Asia. Spain turned west, sending the Italian mariner Christopher Columbus toward East Asia. Columbus never reached his destination because the Americas stood in his way. Following Columbus’s encounter with the Americas, both Iberian kingdoms decided to divide the Atlantic sphere among them. An imaginary line was drawn through the Atlantic Ocean about 370 leagues (roughly 1,300 miles) to the west of the Cape Verde Islands off the coast

of Africa. This agreement, known as the Treaty of Tordesillas (signed in 1494), declared all territory to the west of the line Spanish and everything to the east of the line Portuguese.

This maritime treaty prevented the Spanish Crown from following the Portuguese into the Indian Ocean. Attempts were thus made to investigate a western route to the fabled Spice Islands. Magellan’s arrival in Spain in 1517, together with his cosmologer friend Ruy Faleiro, was thus quite welcomed by Holy Emperor Charles V. Faleiro and Magellan devised a plan to sail to Asia through a not-yet-discovered passage through the south of the Americas.

IN SERVICE TO SPAIN. Magellan’s status as a nobleman, as well as his service in the Indian Ocean, inspired confidence, and Emperor Charles V granted Magellan five ships in March 1518. Magellan set sail with a crew of nearly 270 men on September 20, 1519, and headed southwest into the Atlantic Ocean in search of a passage through South America. He faced incredible setbacks and imminent mutiny by his crew as the search for a passage led them into inhospitable waters. Magellan restored order with an iron fist. Supplies were dwindling, and his men had no choice but to eat anything they could find: worms, insects, rats, and sawdust. To make matters worse, one ship was lost.

With only four ships and short of food, Magellan renewed the expedition that August, and by October 1520, he entered the strait that would later bear his name. So circuitous was the passage that Magellan had to divide his ships to reconnoiter parts of the strait. The crew of the largest ship, the San Antonio, instead deserted Magellan and opted to sail back to Spain. After more than a month Magellan’s remaining three ships at last navigated through the strait and into the Pacific. The passage through this “new” ocean was taxing. Lack of food and the increasing onset of scurvy debilitated the crew. The absence of storm systems in this ocean informed Magellan’s name for the new watery expanse: the Pacific. By March 1521, the expedition reached Guam in the Northern Pacific. Misunderstandings with the indigenous Chamorro people led to loss of life on both sides. A month later, Magellan and some crewmembers were killed on Cebu in the Philippines. Further ship losses reduced the expedition to a single vessel, the Victoria, which, loaded with spices, returned under the command of Juan Sebastian de Elcano to Seville. Only 18 of the original 237 men made it back to Spain. The cargo of spices, however, more than paid for the cost of the expedition.

IMPLICATION OF THE CIRCUMNAVIGATION. Although Magellan did not complete this circumnavigation, his name is forever associated with this feat. The voyage revealed the true dimensions of the globe and that the oceans were not landlocked. It also provided Spain with a way to lay claim to the Spice Islands by sailing westward. Magellan’s circumnavigation forced Portugal and Spain to renegotiate the existing Treaty of Tordesillas. In the 1529 Treaty of Zaragoza, Charles V agreed to cede the Maluku Islands to Portugal in exchange for significant monetary compensation.

FURTHER READING: Bastable, T. 2004. Ferdinand Magellan. Milwaukee: World Almanac. Kaufman, M. D. 2004. Ferdinand Magellan. Mankato, MN: Capstone Press. Kratoville, B. L. 2001. Ferdinand Magellan. Novato, CA: High Noon Press.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 2;