Zoogeography of the Alberta Herpetofauna

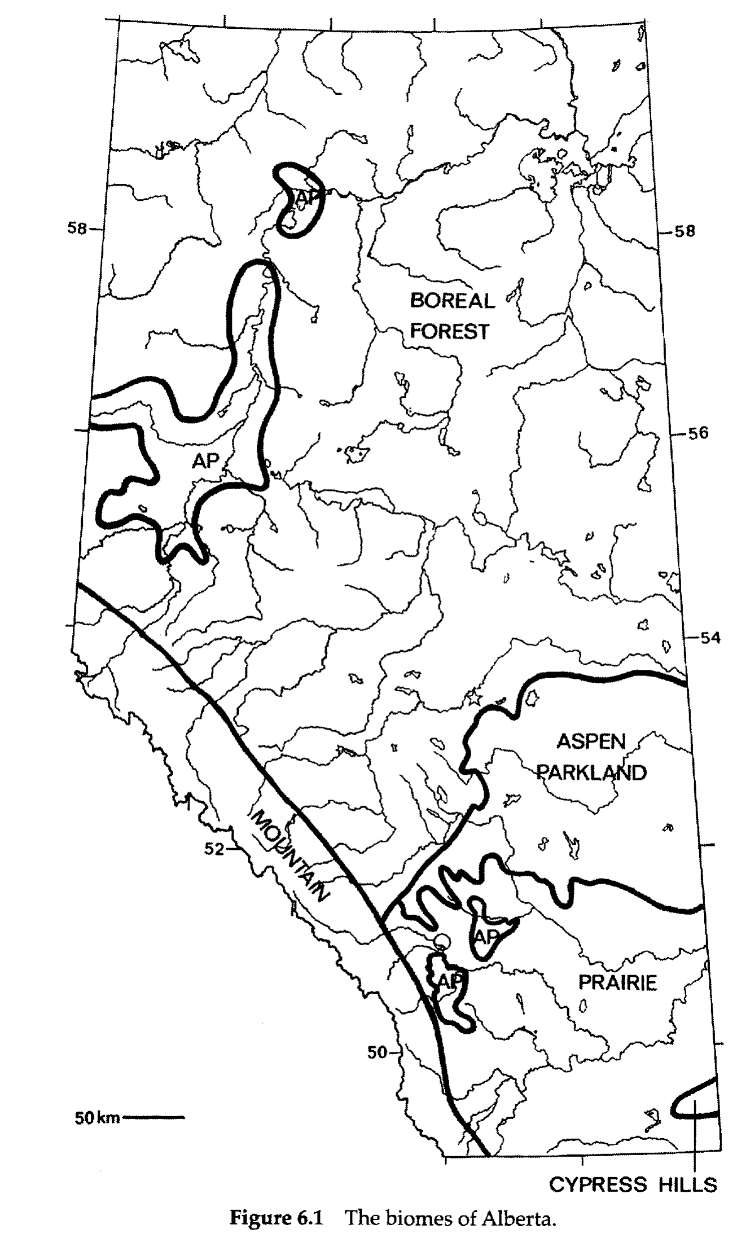

THE 661,000 KM2OF ALBERTA may be divided into four major biomes (Fig. 6.1). Representative terrain from these biomes is presented in the colour plates. The bulk of the southern quarter of the province (121,000 km2) falls within the prairie biome. This is a region characterized by relatively low rainfall (approximately 300 mm/year, chiefly in summer) and high summer temperatures. The dominant plants are grasses, with trees restricted primarily to water courses. The far southeast is exemplified by short-grass plains with arid- adapted plants such as sagebrush. Further north and west, mixed prairie with a more diverse and less arid-adapted flora grade into the other biomes of the province.

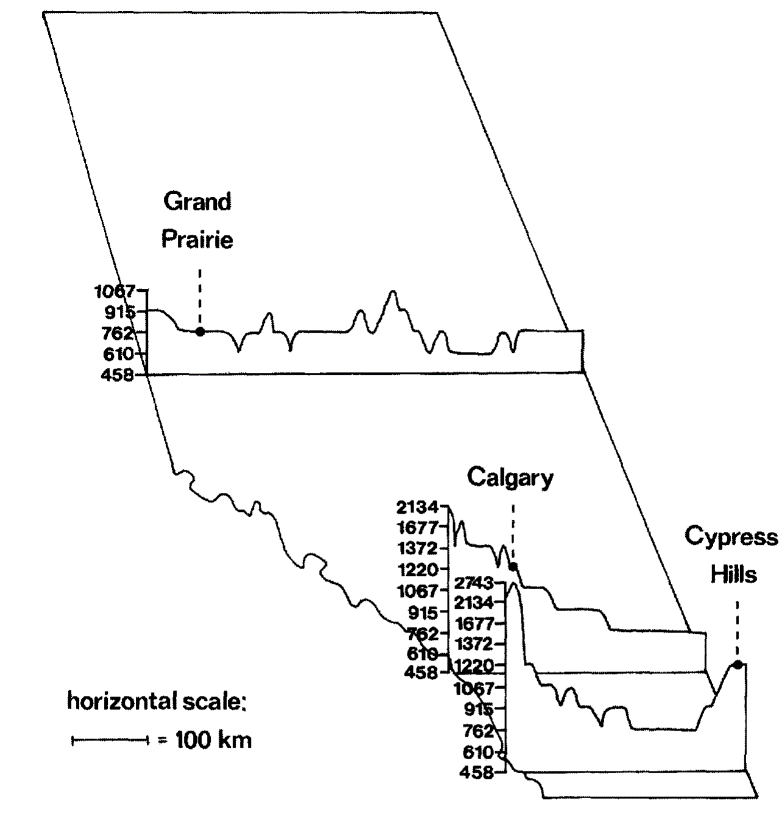

The base elevation of the prairie ranges from 760 metres in the east to 1,250 metres in the foothills of the Rockies (Fig. 6.2). The topographic relief of the region is relatively low, with sand hills and ridges scattered throughout. The Alberta prairie is drained by a series of rivers flowing in a generally eastward direction (Fig. 6.3). The southernmost river is the Milk, which flows south into the United States. Somewhat further north, the Oldman and Bow Rivers join to form the South Saskatchewan River. At the northern limits of the prairie, the Red Deer River, which has its origin in other biomes, flows to the south and east, exiting the province just north of the South Saskatchewan near Empress.

Small streams and drainage channels from the prairie as well as tributaries to the major rivers form deep, often narrow and intricately sculpted gorges and coulees, characteristic of badland topography. These protected passages support a rich flora and fauna and serve as conduits, allowing for the penetration of prairie elements into the parkland to the north. Other coulees may be remnants of pre-glacial river valleys that now incise through the prairie, but no longer serve as major drainage channels.

Figure 6.2 Profiles of the elevation of Alberta represented as east-west cross sections through three locations. Vertical scale in metres (above sea level).

To the north of the prairie lies the aspen parkland of Alberta, an ecotone between the prairie and the boreal forest to the north. Small pockets of parkland occur to the south of the main ecotone, to the east and south of Calgary, and to the north along the Peace River. This is a region of mixed grassland and aspen and willow stands occupying 60,000 km2, chiefly in the eastern part of the province. The region receives 41-46 cm of rainfall per year and has relatively short warm summers and long cold winters, yielding mean annual temperatures of 1-4°C.

The parkland, like the prairie, was affected by glaciation, contributing to its relief. This biome covers rolling to hilly land from 720 to 1,640 metres in elevation (Fig. 6.2). The primary river drainage of the aspen parkland is the Battle River, although the Red Deer River also drains portions of the western parkland. Unlike the prairies, the parkland contains many bodies of standing water, including large and small lakes, sloughs and marshes.

The boreal forest (taiga) region covers the vast majority of Alberta, over 400,000 km2(more than 60 percent of the entire area). This is a woodland or forested zone, divisible into several components. In the west, at the interface with the Rocky Mountains, transition taiga occurs in the foothills. To the east, in central Alberta, lies the boreal mixed wood zone. In the north of the province lies the boreal sub-arctic mixed wood zone, flanked east and west by boreal subarctic alluvial lowlands. Each zone is characterized by a different mixture of dominant tree species. In the southern boreal region, the North Saskatchewan drainage flows eastwards into Saskatchewan.

The Peace and Athabasca drainages flow north into Lake Athabasca, which itself is drained by the Slave River. The Slave and the Hay River in the northwestern corner of the province flow north to Great Slave Lake. Although elevation rises from 985 to 1,970 metres as the forests enter the foothills, much of the region has low relief (Fig. 6.2), owing to the glacial scouring experienced by northern Alberta. The region is relatively moist (400-600 mm/year) and experiences long cold winters and short cool summers.

The last of the major biomes of Alberta is the Rocky Mountains proper. Reaching a maximum elevation of 3,747 metres at Mt. Columbia, the great elevational range and the associated vagaries of direction of slope face and local microclimate combine to make the mountains a vegetationally diverse region. Only at the highest elevations do coniferous and / or deciduous forests give way to tree-less alpine tundra.

Many of the major rivers of the province take their origin in the Rockies, most being derived ultimately from snow melt. Typically the headwaters flow eastward to water the other biomes of the province. The climate is cool and winters are exceptionally long (125-155 frost-free days). While some areas may receive reasonable amounts of rain, most moisture is derived from winter precipitation.

In addition to the four major biomes outlined above, a small region of Alberta's southeast, the Cypress Hills, may be classed as a separate biome of its own. The Hills occupy about 900 km2in Alberta and an additional 1,680 in Saskatchewan. They are actually a plateau, with its highest point at 1,580 metres at the western edge. Although they lie within the dry prairie belt, the higher elevation of the Cypress Hills yields a cooler temperature and higher rainfall than the surrounding plains. The hills support coniferous and deciduous forest. While only the very summit was not covered by glaciers in the past, the Cypress Hills seem to have preserved faunal and floral elements reflecting earlier ties to the Rockies via a now-defunct forest belt.

The divisions between the various biomes are not precise: overlap occurs and pockets of one type may be found within another. The biomes themselves are defined by the vegetation they support but are determined by a combination of existing and historical factors, primarily geological and climatic. The area that is now Alberta was mostly or entirely submerged beneath a series of encroaching embayments and epicontinental seas throughout long periods of its history. During the Devonian (408-360 million years before present—mybp) and Cretaceous (144-65 mybp) very little of the province was emergent.

During the latter period, the chief episode of mountain building resulted in the upthrust of the Rocky Mountains, which continue to rise, move and change shape. During the Cretaceous, as for much of its history, Alberta enjoyed a mild or even tropical climate. Under these conditions, the province was able to support the impressive dinosaur fauna that is so familiar to most Albertans. Later, during the Oligocene (37-24 mybp), the Cypress Hills supported a subtropical herpetofauna with relatives of existing species including Ambystoma and Spea, but also boas, amphisbaenids and crocodylians.

During the late Pleistocene (ca. 35,000 ybp) Alberta became affected by glaciation. A series of glacial and interglacial periods had characterized the preceding 965,000 years, but had not directly impacted upon this region of Western Canada. During the most recent glacial period, all of Alberta, except the higher elevations of the Rocky Mountains and the summit of the Cypress Hills, was covered by ice. The final retreat of the glaciers began approximately 12,000 ybp.

Essentially all vegetation in Alberta, and all animals as well, were wiped out or pushed far to the south during the glacial periods. Consequently, present distributions of the biota, including amphibians and reptiles, have been determined only within the relatively short time since the retreat of the ice sheets. For the herpetofauna, the time is shorter still, since most species would not have been able to occupy the newly ice-free environment until after vegetational communities and arthropods had reestablished themselves. Further, lower temperatures near the retreating edges of the glaciers would have left an ever-moving buffer zone not immediately suitable for occupation by poikilothermic (cold-blooded) vertebrates.

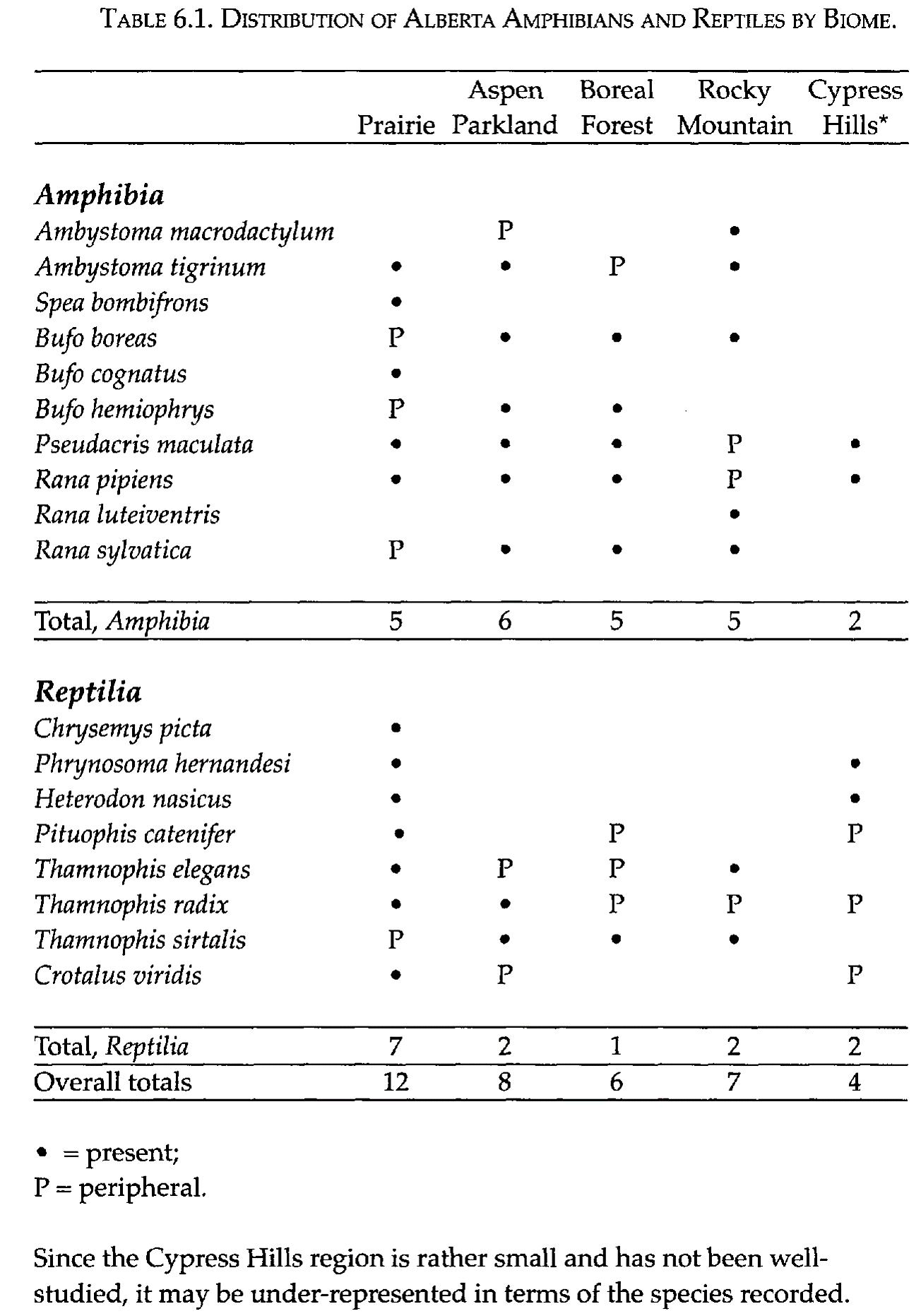

The southern and eastern portions of the province have been free of the glaciers longer than the north and the mountains. It is this region, corresponding to the prairie biome, that has the warmest temperatures and lowest rainfall, and it is this region in which amphibians and reptiles are most diverse (Table 6.1).

This diversity is expressed to its fullest in the short-grass plains of the southeastern corner of Alberta, and it is here that one finds those species that are typically arid-adapted. The richness of this region is reflective of the herpetofauna of adjacent regions of the United States. The arid and semi-arid states of the Rockies and northern Great Plains are the major source areas for Alberta amphibians and reptiles, and taxa that have reasonably wide tolerances have been able to move as far north as the prairies of the province. Species that occur elsewhere in Alberta tend to be extreme generalists, or cool- / moist- adapted animals that may have moved into Alberta along a western, mountainous corridor or that followed the retreating glaciers northward, remaining in a cooler climatic belt, such as the modern boreal forest.

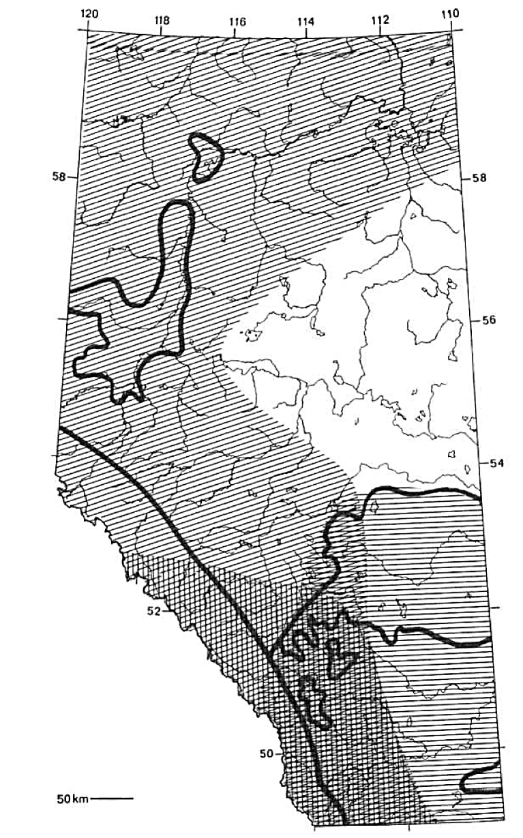

Of the reptiles, seven of the eight species occur within the prairie region. Three of these, Chrysemys picta, Phrynosoma hernandesi and Heterodon nasicus are absolutely restricted to this region and the low elevations of the Cypress Hills. In addition, Pituophis catenifer and Crotalus viridis extend out of the prairies only marginally, and may be considered as typical prairie species. The remaining reptile genus, Thamnophis (the garter snakes) is widely distributed throughout the province. Each of the three species, however, is centred in a different region (Fig. 6.4).

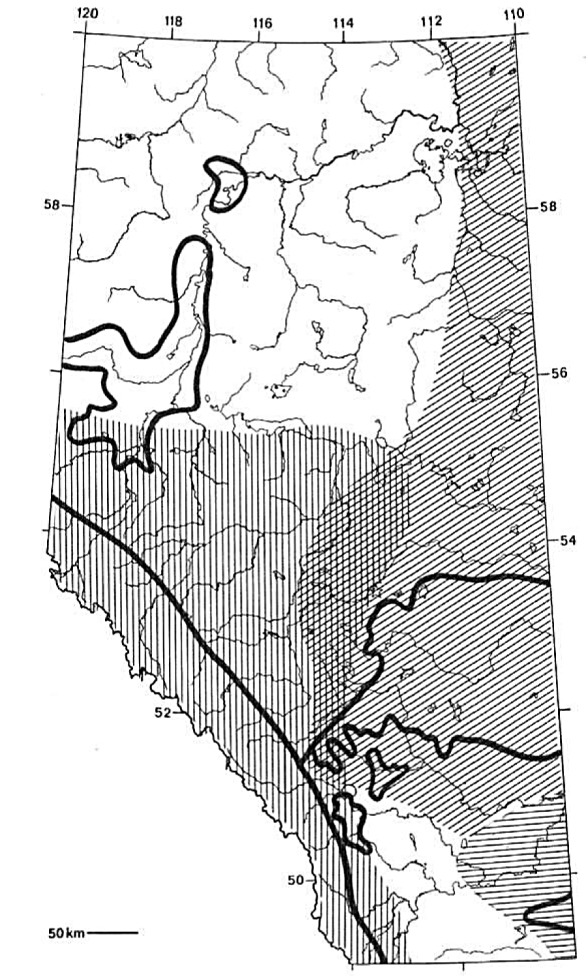

Figure 6.4 Distributional patterns of the three species of garter snake native to Alberta, showing areas of overlap and areas of exclusivity. Diagonal lines: Thamnophis sirtalis; vertical lines: T. elegans; horizontal lines: T. radix. The heavy black lines represent the outlines of the biomes (see Fig. 6.1)

Thamnophis radix, which reaches its western limit in Canada in Alberta, is centred in the prairie region but extends northward to the aspen parkland (it is marginally distributed in other biomes). T. elegans is also found chiefly in the south, but is more common than radix in the mountainous west. Its distribution in the north is poorly documented, but it seems to be largely absent from the boreal forest, where it is replaced by Thamnophis sirtalis, a chiefly northern, cool-adapted form. This last species is the only reptile species in Alberta that is not typical of the prairies. Indeed, most aspects of its biology (see pp. 110-113) are those of an animal specialized for surviving and reproducing in very cold regions with short activity seasons.

Two species of Alberta amphibians are restricted to the prairies only: Spea bombifrons and Bufo cognatus. Both species require sandy soil for burrowing, intermittent periods of heavy rainfall and high summer temperatures for successful breeding, conditions generally only met in the south of the province. The two remaining species of Bufo are generally absent from the prairies but segregate to some extent in the other biomes (Fig. 6.5). The western toad, B. boreas, occurs in the aspen parkland, boreal forest and mountain regions. In general, it is most common in the western parts of the province. The Canadian toad, B. hemiophrys, is chiefly an eastern species and, like Thamnophis sirtalis, is a northern specialist.

Figure 6.5 Distributional patterns of the three species of true toads native to Alberta, showing areas of overlap and areas of exclusivity. Diagonal lines: Bufo hemiophrys; vertical lines: B. boreas; horizontal lines: B. cognatus. The heavy black lines represent the outlines of the biomes (see Fig. 6.1)

Ambystoma macrodactylum and Rana luteiventris are largely restrict- ed to the mountains, the former species having recently been found at lower elevations in the vicinity of Fairview. In many respects, the environmental conditions here are similar to those of higher elevations further to the south. Their habitat preferences are for cooler waters, and they are representatives of montane groups that occupy high elevations throughout western North America.

Within the mountains, several aquatic habitat types, differing in water temperature, depth, permanence and flow rate, occur, and the specific distributions of these and other amphibians that reach the Rockies are determined by these microhabitat differences. Tiger salamanders, Ambystoma tigrinum, are chiefly animals of the prairies and aspen parkland. This species reaches the borders of the Rockies and has scattered populations in the boreal forest. Typically, this species occupies burrows, so the soils of the south are particularly suitable for it. Its distribution in the north is confused somewhat by the availability of artificial breeding sites (e.g., dugouts) and the artificial introduction of larvae as bait by fishermen.

Pseudacris maculata does not occur at high elevations, but is common throughout the rest of the province, from the prairies to Lake Athabasca. It is a widespread species in much of North America and has broad tolerance levels. It appears to be able to utilize ponds or marshes wherever they occur. Northern leopard frogs, Rana pipiens, have declined in Alberta, but were formerly common chiefly in the prairie regions and the Cypress Hills. Records, however, are scattered as far north as the border of the Northwest Territories, but the distribution in the north of Alberta is poorly understood and needs to be investigated more thoroughly. Finally, Rana sylvatica is a non-prairie form. Like some of the previously mentioned taxa, it is a cool-adapted specialist and is even able to withstand freezing of its body fluids. It occurs in all of the remaining biomes, and its presence in the region of the Cypress Hills illustrates the early post-glacial connection to the west described above.

The species discussed in Chapter 5 as forms which might occur in Alberta would divide into two distributional categories. The snapping turtle and racer both represent southeastern forms, which could only enter the province through the grassland regions of Montana. These would be prairie-restricted species. The tailed frog and rubber boa, however, are western species, whose only corridors into Alberta would be via the Rocky Mountains of British Columbia or western Montana. The requirement for cool, forested regions would most likely limit both to the mountains of the province.

Significant references: Alberta Energy and Natural Resources, Fish and Wildlife Division 1984; Braithwaite 1970; Brode and Bury 1984; Cook 1964a; Gorham 1957; Hardy 1967; Harper 1931b; Holman 1972; Hovingh 1986; Lewin 1963a; Longley 1972; Minister of Supply and Services, Canada 1986a, b; Russell and Bauer 1991; Savage 1973; Schall and Pianka 1978; Shmida and Wilson 1985; Williams 1946.

Date added: 2022-12-11; views: 602;