Blacktail Deer. Mule Deer. Characteristics. Breeding. Range and Distribution

Characteristics. The wariness of the blacktail is much like that of the whitetail. He is cautious and careful as he moves through his timbered country, showing little of the notorious curiosity of the mule deer. If he is pursued, his flight is, unlike that of the mule deer, brief. He attempts to elude by skulking or remaining quietly in hiding.

When the mule deer picks a bed, he pauses every now and again to watch his tracks, as he does when pursued, to see if he is being followed, and usually backtracks to his chosen spot.

Deer vary. Some are intelligent, some stupid, and they should be judged individually; but the blacktail on the average is considered more canny. He avoids any open space, which a mulie would cross, and carefully skirts the selected bed, which is always a lookout station over canyon, valley, or plain in order to have the advantage position on an approaching enemy.

When alarmed and attempting a quick getaway, both the mule and the blacktail use a peculiar stiff legged hop which has given them the name "jumping deer." This gait is spectacular but quickly tires them. They jump high with all four feet drawn together and land on all four at once. The y cover about IK feet with each leap. The fawns are the most skilled at leaping, scarcely seeming to touch the ground between bounds.

The mule deer utilizes this gait on the rough terrain of his habitat, but when the blacktail is calm, he uses a moderate gallop for speed. Both species have a clumsy, shuffling walk.

The first natural enemy of the deer was the timber wolf, which developed through evolution primarily as a natural check on the growth of the deer population. Few deer today die under the fangs of the wolf, since predator-control programs have all but eliminated the wolf except in the northern fringes of the deer range.

The cougar locally takes a high toll of blacktail and mule deer—up to a hundred a year for each adult lion. But the cougar hunts over a territory of more than 100 square miles, which usually contains from ten to twenty deer to the square mile, as well as a considerable number of other potential cougar foods.

Coyotes also kill mule deer and blacktail fawns; occasionally packs will pull down adults. But most biologists agree that more mule deer are lost to winter starvation and disease because of overprotection than to any other cause.

When there are too many deer in the winter, spring finds the survivors subject to the deadly attrition of parasites (nose bots, ticks, lung worms, heart worms, etc.) and virus diseases.

Like other deer, both mule and blacktail habitually band up in the winter with a mixing of both male and female, but with spring they separate, going off alone or in twos and threes. The bulls often form larger groups of about six to ten. A common combination among the mule deer is a large bull with a smaller one.

Their feeding habits have been likened to those of grazing cattle—eating in the morning and then resting until they eat again in the afternoon. Like the whitetail, the mule and blacktail graze on grass and other vegetation, and browse on numerous types of foliage and shrubs. The northern Sitka blacktail eats kelp when forced down to the saltwater edges in the winter season.

Breeding. The breeding habits and the birth and care of the fawns of the mule and blacktail deer are much like those of the whitetail (q.v.). Rut begins in late fall, at which time there occurs the characteristic swelling of the buck's neck, which in the mule deer is tremendous; his neck becomes almost as big around as his body.

The bucks will fight viciously to collect a harem which averages from five to seven does, but some-times as many as 15. Once a harem is established, however, the violent question of ownership dies down somewhat, for it is not uncommon for a buck with his does to be followed by from one to three young bucks which the successful conqueror has little trouble keeping in line.

In some areas, where the deer are actively hunted, the bucks remain at a higher level during the day-time, coming down to the does only during the night.

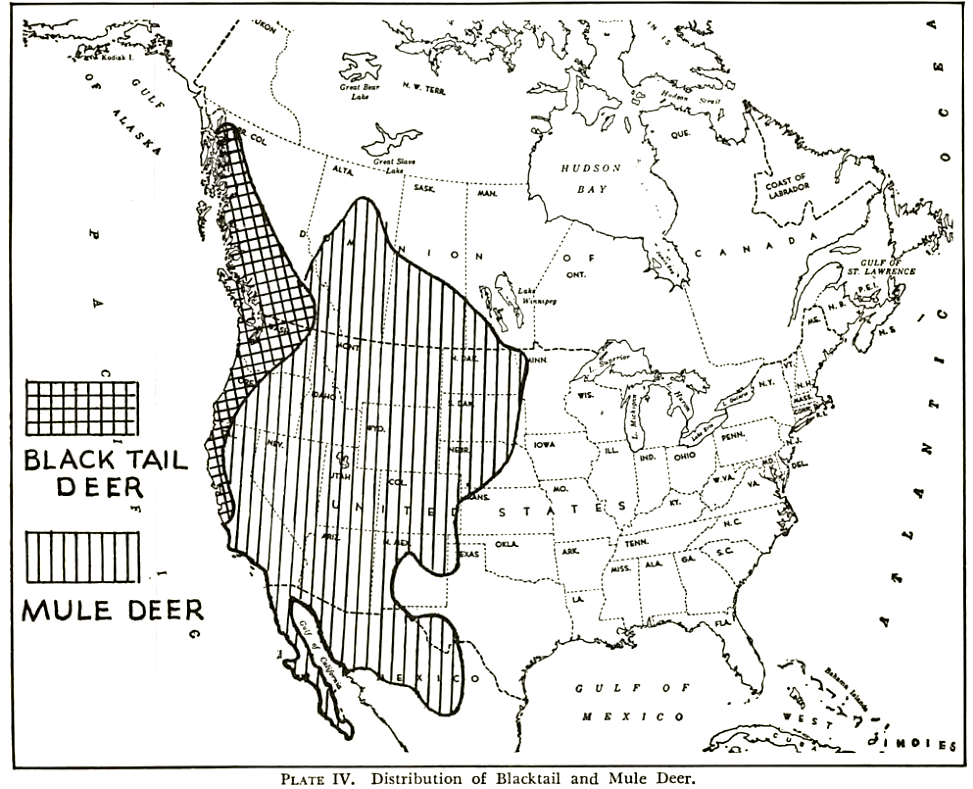

Range and Distribution. The range of the blacktail deer is one of the most confined of all our American deer. It is restricted to the Pacific Coast, from Sitka, Alaska, to Southern California, extending east to the crest of the Sierra Nevada and Cascade Mountains, and remaining with in the rain belt.

The blacktail is a typical "edge" dweller, a lover of the broken country, of heavy underbrush and dense forest borders. In the north he seeks cedar, spruce, fir and in the south he is found in the chaparral country and among firs and redwoods. His preference for the redwood forests of California has given him the nickname of "red wood deer." He thrives in the humid areas of the coast where the heavy rainfalls provide an abundant under growth up on which he can browse.

The blacktail is migratory and changes his habitat with the seasons. On the inland ranges winter drives him from the upper levels of the mountains to the lowland shelters of timbered country. He travels as much as too miles when he makes these yearly trips. A t one time, when civilization did not obstruct their line of march, the deer would stamp out a set path leading down from the mountains which they used every year, with the does and fawns in front, then the young bucks, followed by a guard of old bucks in the rear. In the spring the deer go back once again to the mountains, where they remain all summer. Such a migration is not necessary, however, for the blacktails of the coastal ranges, where there are no severe weather changes to affect the food and shelter of the area.

The mule deer ranges over rough country along the Rocky Mountains from British Columbia to Mexico.

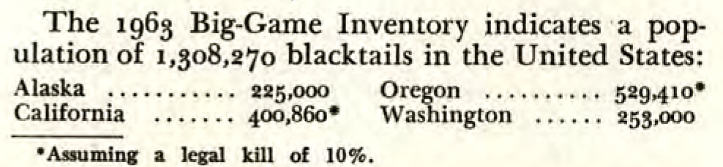

The population of the mule deer in the United States indicated by the 1963 Big-Game Inventory totaled 5,979,040, as listed below by states:

His range is wide and he is at home on plains, foothills, and mountainsides. He inhabits the wooded river bottoms of the Great Plains, mountain forests of California, and deserts and plains of Sonora.

Large herds, often number in gas many as 1000, gather in the fall to start the winter migration. The food crisis comes about the end of December; then they travel too miles or more from the craggy mountain slopes to lowlands. It is the heavy snowfall, not the cold, which forces this migration.

Mule deer used to winter on open sage flats, but today they venture little farther than the fringes. This inadequacy of winter ranges, often grazed and browsed clean by sheep and elk, curtails the mule deer's numbers in the Rockies.

With the oncoming spring they retreat to the mountains, keeping about three miles below the snow-line where the coyotes lie in wait to force a lone wanderer onto the crust.

Date added: 2022-12-11; views: 1350;