Industrialization and Heavy-Metal Pollution

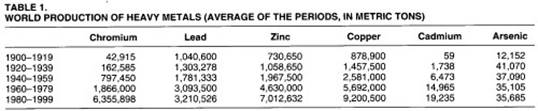

Increased metal consumption is considered one of the best indicators of material progress. Since the industrial revolution, the production of heavy metals has increased exponentially, which has caused a constant increase in human-caused emissions of toxic metals into the atmosphere.

The relative weight of the different sources of emission has varied, depending on the industrial intensity and technological trajectory. Mining, the metal industry (especially nonferrous metals), and certain branches of the chemical industry continue to be the main contemporary human sources of heavy- metal emissions.

A large portion of heavy-metal pollution comes not from production, however, but from domestic and industrial waste, especially into aquatic environments (rivers, lakes, and oceans). Incineration of urban and industrial residuals, used in numerous countries as an alternative to letting waste accumulate in dumps, is one of the main sources of dioxins and toxin heavy-metals emission.

The combustion of fossil fuels (especially coal, oil, and wood) to produces electricity and heat is also a major cause of contamination. Coal burning, a major source of energy of the early industrial revolution and the most affordable for developing countries, is the major source of mercury, arsenic, chromium, and selenium pollution, while oil is the most important source of nickel and vanadium pollution

If we consider in an individualized way the problem of the main polluting metals, lead is probably the worst offender. Lead is used in the production of other commodities and also in storage batteries, additives for gasoline, pigments and paints, electric-cable coverings, glassmaking, ammunitions, roofing, and in linings for water pipes and systems for the processing and transport of corrosive chemicals.

Air emissions (primarily sulfur oxides and paticulates, including lead oxides, arsenic, and other metallic compounds), and solid and liquid wastes (containing antimony, arsenic, copper, tin, and other elements depending on inputs), are the polluting substances linked to lead production.

Although lead used in metallic form is easily recovered as scrap and reused for new applications, when it is in chemical compounds, it generally dissipates into the atmosphere and is not recoverable. Chemical compounds containing lead are found in certain insecticides, paint pigments, and leaded gasoline, products whose toxicity has created serious air pollution problems.

At the present time mercury is used primarily for different electrical applications, such as electrolytic processes to obtain chlorine and caustic soda, and to remove impurities from other metals, as well as in wiring devices and switches, fluorescent lamps, batteries, and measuring and control instruments. In addition to the pollution associated with the production of these devices, products containing mercury pose a hazard when they are disposed of, whether they are deposited in dumps or incinerated: the mercury ends up either in the soil or groundwater, or in the atmosphere.

When mercury makes its way into aquatic ecosystems, its toxicity is increased by microbial activity, which converts it into methyl mercury, a highly toxic organic form of mercury. In these cases, bioaccumulation in the food chain can cause serious health problems, such as the famous case in Minamata, Japan, in which the ingestion of fish contaminated by effluent from Nippon Chyisso Hiryo Company (a chemical company), gave rise in 1956 to a toxic syndrome known as the Minamata disease. Mercury-contaminated water also affects the quality and fertility of soil, reducing its yield and damaging agriculture and livestock.

Copper consumption has gone down in recent decades as other materials are used in its place (aluminum for wiring, fiber-optic cables in long-distance communications, and plastics for plumbing, for example), but it continues to be in wide demand, both as a primary product and as a compound with other metals.

Copper is now frequently used in electrical and electronic products; machinery and equipment; transportation, chemical, and medical processes; fungicides; wood preservatives; and pigments. Air emissions (sulfur dioxide and particulates containing copper and iron oxides, sulfates, and sulfuric acid) from the smelting process and wastewater produced in electrolytic refining procedures are the main pollution problems in the copper industry.

Zinc is the fourth most widely used metal after iron, aluminum, and copper; it is one of the most important industrial metals. It is predominatly used as an input in the production of other commodities. It is used to galvanize other metals (galvanization helps metals resist corrosion), in die casting for the automotive and construction industry, in the electrical and machinery industries, in alloys with copper (primarly to produce brass), and in chemical compounds, pharmaceuticals, and paints.

Sphalerite (zinc sulfide) is the most common mineral used in zinc production, and sulfur dioxide, a by-product of the roasting process, is the biggest pollutant in the industry. The slags from zinc production also contain copper, aluminum, iron, and lead.

Arsenic is a natural element of the Earth's crust but is an environmental pollutant, especially when it enters acquifers and water supplies. The contamination can be caused either by natural deposits in the Earth or by human agency. Tin and copper mining and smelting, coal burning, and pesticides used in agriculture are the main human sources of arsenic pollution.

Nickel, although used from the antiquity in alloys with copper in the coinage of currencies, was not identified as a metal until 1751. At the moment it continues to be used as an alloying metal in the manufacture of stainless steel and other ferrous and nonferrous alloys, increasing hardness and resistance to heat and corrosion.

Other heavy metals, including chromium, cadmium, and selenium, were not discovered until recently, and their industrial use has been developed mainly during the twentieth century. Their environmental and health impacts are very different. For example, while chromium does not bioaccumulate in the food chain, cadmium is an extremely toxic metal, and selenium, although toxic above certain levels, is an essential trace mineral in the human body.

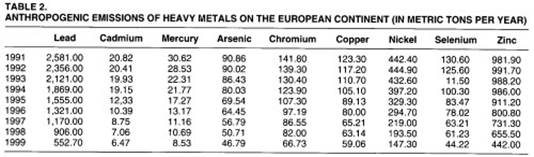

Trends. After a long period of intense and continuous increase in human sources of heavy metals, the last decades of the twentieth century demonstrated a significant new trend. The economic crisis of the seventies, the technological change and the application of more rigorous environmental policies, especially in the developed countries, have led to a desire to reduce the emissions of heavy metals. (See tables 1 and 2.)

Although economic growth continues to be linked to the production and consumption of heavy metals, their emissions, especially in developed countries, are now controlled, thanks to the significant improvement in pollution control technologies and to strict public regulation and legislation.

The emissions of heavy metals per unit of heavy metal processed is generally decreasing. To some degree, however, the regulation and control measures adopted in the developed countries has merely meant that polluting activities have been displaced to less restrictive and generally poorer countries.

Keeping in mind that contamination can exist thousands of kilometers away from the source of pollution, it will serve the world well to adopt the most comprehensive possible international agreements and programs to control emissions.

Date added: 2023-09-23; views: 778;