Space. Fictional Roots. Military Funding

Space technology has a unique place in the history of twentieth century technology, since it concerns the application of technology beyond the confines of the earth. In engineering terms, this has involved communications (since signal travel time may be measured in minutes), ruggedness (since spacecraft must survive a hostile thermal and radiation environment), and reliability (since spacecraft beyond low earth orbit cannot be retrieved or repaired).

Space technology is also unusual because it is both a user of other technologies—electrical, electronic, mechanical, power, computing, and telecommunications—and a developer of these technologies. The challenge of developing systems that operate reliably in the space environment and hardware that is sufficiently light and compact to be launched in the first place is so great that developments in space technology often led to improvements in earthbound systems. One example is the microminiaturization of electronic components required for early spacecraft, which drove the development of electronics and computer systems of the late 1950s and early 1960s.

The degree to which this “spin-off” occurred is difficult to prove, since it is impossible to remove the influence of space exploration and development from the history of the twentieth century. However, the subject has proved itself to be important in at least two main ways. First, space is important as a place to go: as the mountains and the oceans have to past explorers, it provides a goal and a challenge with which to satiate mankind’s inherent desire to explore (summarized for many in the phrase ‘‘the final frontier’’). Second, space is important as a platform from which to provide services: from satellite communications and GPS navigation, to remote sensing of the earth and the cosmos.

Here, we look at the development of space technology in the twentieth century, from its roots in science fiction to its industrialization and later commercialization. We discuss the impact of its various applications on society and its influence on culture in the second half of the century. Although these factors have varied in degree from nation to nation, space technology has had a global impact; indeed it has been a key factor in the development of ‘‘globalization’’ itself.

Fictional Roots. It seems likely that space travel has been part of human imagination since mankind realized that space was ‘‘somewhere to go.’’ As a planet, earth is unusual in that it has a moon that appears relatively large in its sky, and even with the naked eye, considerable detail is visible on its surface. This alone must have evoked speculation as to the possibilities of traveling there, even before the invention of the telescope.

Although thirteenth century China is credited with the invention of the rocket, Cyrano de Bergerac is believed to have been the first to propose that rockets should be used as a form of space propulsion. In his novel The Comic History of the States and Empires of the Moon and the Sun, published in 1649, he imagined being raised aloft by rockets attached to a flying machine.

Jules Verne, however, is credited with writing the first fictional account of spaceflight based on scientific fact: From the Earth to the Moon, which appeared in 1865. Since the bullet was by far the fastest thing in Victorian life, his fictional spacecraft was a bullet-shaped projectile propelled by a cannon. Verne’s first astronaut crew would have been pulverized by the acceleration, but at least he had recognized the need for speed to escape the earth’s gravity as described by Newton in the seventeenth century.

Once the technology of ‘‘moving pictures’’ had been developed, it was inevitable that it should be used to portray what we now call science fiction. Indeed, a number of science fiction ‘‘shorts,’’ of only a few minutes in length, were made prior to 1900. However, the first feature-length (21-minute) science fiction film was Le Voyage dans la Lune (A Trip to the Moon), made by George Melies in 1902; it was inspired by Verne’s From the Earth to the Moon and H.G. Wells’ The First Men in the Moon. Thus began a long line of space-related films which, for some, culminated in the 1968 classic 2001: A Space Odyssey, released the year before Neil Armstrong became the first man to set foot on the moon.

Military Funding. The early pioneers such as Konstantin Tsiolkovsky and Robert Goddard (see entry on Rocket Propulsion, Liquid Propellant) received little pub lic support or government funding for their early work, and in common with many technologies, the development of the rocket was driven by the needs of warfare. In 1932 Wernher von Braun was employed by the German army’s rocket artillery unit to develop ballistic missiles.

In World War II, the result was the V-2, which later became the basis for both Russian and American rocket programs. Indeed, it was Wernher von Braun who became the leading proponent of, first, the U.S. Army’s and later, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s (NASA’s) space exploration programs of the 1950s and 1960s, culminating in his work on the Saturn-V moon rocket (see Figure 14).

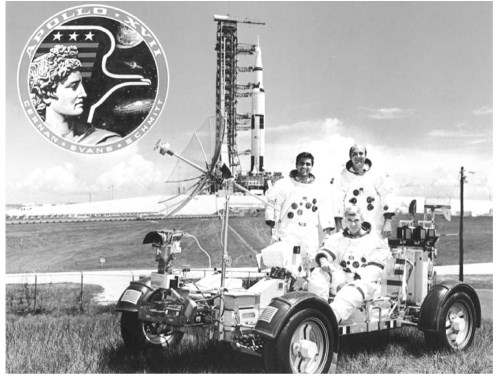

Figure 14. The Apollo-17 astronauts (Harrison Schmitt, Ron Evans and Gene Cernan) pose in their lunar roving vehicle (LRV) in front of the Saturn-V rocket that took them to the moon. Apollo-17, launched in December 1972, was the final mission in the Apollo program and the third to carry an LRV to the moon

Even today, it is difficult to reach a consensus on so-called ‘‘dual-use technologies,’’ such as rockets and remote sensing satellites: the former can be used as spacecraft and weapon delivery systems and the latter can provide high-resolution images for both civil and military applications. Although the same dichotomy exists in the use of aeroengines, terrestrial surveillance systems and computer technology, a satellite-targeted, global positioning system- (GPS-) guided, nuclear-tipped intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) has far greater destructive potential.

Date added: 2023-10-27; views: 666;