Old Kingdom (Third-Eighth Dynasty, c. 2686-2160 BC)

The Old Kingdom, also called the Pyramid Age, is a continuation of the Early Dynastic Period. It was a time of long, uninterrupted economic prosperity and political stability. The central administration was at the capital at Memphis under a vizier who was the highest official. Upper Egypt, the land south of the capital, and Lower Egypt, the Nile Delta to the north, were divided into ‘nomes’ that were governed by nomarchs who maintained strong ties with the court.

The state was able to consolidate its borders in the south and north and maintained long-distance trade with the Levant and Nubia. A redistributive economic system with palaces, temples, royal domains, and mortuary complexes served as centers for collecting, storing, and distributing mainly agrarian produce.

The long reign of Pepi II (c. 2278-2184 BC) at the end of the Sixth Dynasty has often been seen as a time of stagnation and decline that ultimately brought down the regime of the central government but other factors such as worsening climatic conditions causing droughts and famine may have contributed to the fragmentation of the centralized regime and the growth of regional power in the hands of the nomarchs.

At the top of Egyptian society stood the divine king. His funerary complex became the focus of royal ideology and ignited large-scale building programs never seen before. More than a dozen pyramids, as stairways to heaven for the deceased king, were built close to the capital in the area of Giza and Saqqara.

Royal Tombs. Royal tombs of the Early Dynastic Period were built almost entirely of sundried mud-bricks, wood, and reed with the use of stone limited to the interior of tomb chambers and stelae which were large stone slabs with the kings’ name on them. It was at Saqqara in the Third Dynasty that Egypt’s first monumental stone structure was erected for King Djoser (c. 26672648 BC).

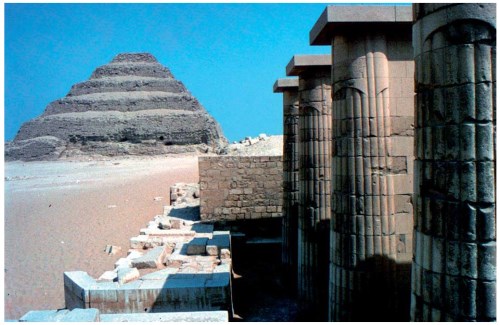

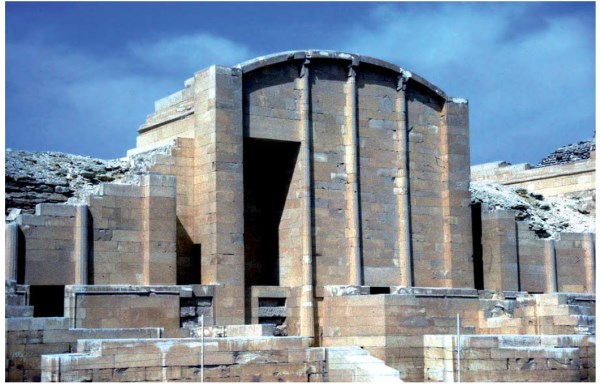

His funerary complex, including the Step Pyramid and ceremonial buildings, transformed the organic building materials into their limestone equivalent (Figures 1 and 2). The enclosure wall of the complex measured 544 x 277 m and was 10.5 m high. The Step Pyramid itself, located to the north of a large courtyard measured 121 x 109 m and its six steps stood 60 m tall.

Figure 1. Step Pyramid of Djoser at Saqqara (Third Dynasty)

Figure 2. Festival court of Djoser complex at Saqqara (Third Dynasty)

The pyramid was actually begun as a mastaba, the Arabic word for ‘bench’, which the tomb resembled. It was enlarged twice before it was altered into a four-step pyramid and finally augmented to six steps. Underneath the pyramid lay a shaft (7 m square and 28 m deep) culminating in the burial chamber. Originally made of limestone with stars on the ceiling it was later replaced by a granite chamber.

Nothing of the king’s interment was found. Also underground was a system of about 400 rooms and corridors, totaling almost 6 km in length. The whole gigantic royal complex at Saqqara symbolizes the focal point of Egyptian society and culture in the Old Kingdom: the divine king.

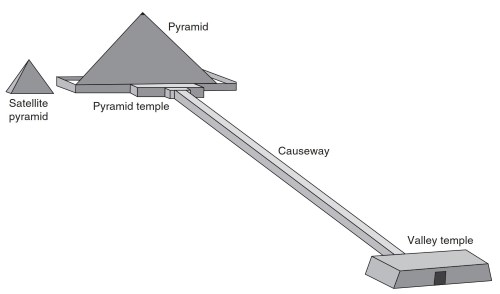

There were at least two more step pyramids of the Third Dynasty before, at the beginning of the Fourth Dynasty under King Snofru (c. 2613-2589 BC), the final design of a true pyramid was realized. The design of the pyramid complex is very standardized. Each has an axis with an east-west orientation, which underlines the structure’s solar aspect. From the valley temple at the eastern entrance (Figure 3), a causeway leads further to the west and ends in the mortuary temple, situated at the foot of the east side of the pyramid.

Figure 3. Standard pyramid complex of the Old Kingdom

This temple has several chambers including an inner sanctuary furnished with a stela, which is set directly against the pyramid. Despite this standardized pattern, however, no two pyramids were exactly alike. The interior chambers and ascending and descending passages were always different. Starting in the Fifth Dynasty, the walls of these chambers and corridors could be decorated with the so-called Pyramid Texts, a collection of funerary texts of about 800 spells.

The main building material for the pyramid was limestone although granite was also used for the lower casing blocks. In the pyramid temples basalt was also sometimes used for the floors. Separate smaller pyramids were erected for the queens while higher officials, often blood relatives, were buried in the limestone mastaba tombs in the necropolis nearby.

Private Tombs. To date, dozens of Old Kingdom cemeteries have been found throughout the country. The major cemeteries for officials, however, were at Saqqara, Helwan Dahshur, Giza, and at Abusir, where they could remain close to the king in the afterlife also.

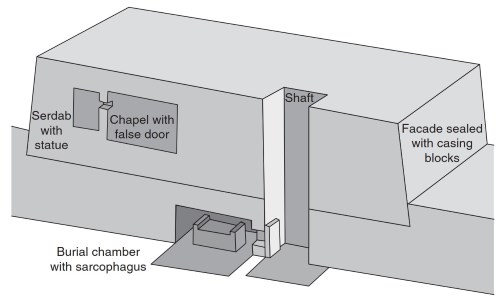

While the majority of the Egyptian population was buried in simple pits in the desert sands, the wealthier could afford rock-cut tombs or mastaba tombs. An early mastaba tomb comprised a subterranean structure with a shaft, a burial chamber and store rooms (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Mastaba tomb of the Old Kingdom

The store rooms disappeared by the Fourth Dynasty. The superstructure was made of mud-brick or stone and its layout became more and more elaborate with the addition of multiple rooms which effectively turned it into a funerary chapel. Scenes of daily life, mostly related to farming, herding, and craftwork, were depicted on the walls of these rooms, along with representations of the tomb owner, his relatives, and his household members.

During the funerary cult the family could bring their offerings to the deceased which they presented on an altar in front of the false door. In a hidden chamber, called a serdab, a statue of the deceased was placed, thus allowing him to accept these offerings symbolically. An offering formula on the wall next to the false door secured the eternal sustenance of the deceased.

Sun Temples and Provincial Temples. A special temple, which was built in addition to the pyramids, developed during the Fifth Dynasty. It was a temple dedicated to the sun god Re. It had similar architectural features to the pyramid complexes including a valley temple functioning as a gate or an obelisk-like structure erected of stone blocks rising up on a pedestal. In one case the pedestal was 20 m high and the obelisk 36 m tall. An open space in front of the obelisk contained an altar where offerings were presented.

Located on one side of the large courtyard were magazines and rooms that have been interpreted as slaughterhouses. Parts of the upper temple were decorated with royal jubilee scenes and scenes from nature. The whole structure was surrounded by an enclosure wall. Outside the wall a brick-built model of a solar boat for the god was found. Six sun temples are known from texts but only the ones of King Niuserre and Userkaf from the Fifth Dynasty have been found at Abu Gurob, 10 km southwest of Cairo.

While royal building activities were concentrated around the capital at Memphis, temples in the rest of the country largely comprised sanctuaries which were built and maintained by local communities. Provincial temples followed no specific design and were often of modest size. The Old Kingdom temple on the island of Elephantine opposite modern Aswan, for example, consisted of mud-bricks enclosing a niche between granite boulders and measured only c. 7 x 7 m.

Date added: 2023-11-08; views: 570;