The Nubian Early C-Group and the Egyptian Old Kingdom

At the dawn of the Egyptian Old Kingdom (Dynasties Three to Six, ca. 2685-2150 вс), which corresponds to the Nubian Early C-Group, a now strongly centralized and prosperous Egypt desired the commodities of Nubia, including gold, exotic animals, ivory, ebony, and incense. The allure of Nubian goods led Egyptian kings to begin a long series of incursions into Nubia to secure them.

Initial efforts to establish trade relations, as well as military campaigns during the Early Dynastic Period, had set the stage for a more complex arrangement during the Old Kingdom The Egyptian expansion into Nubia during the Fourth and Fifth Dynasties (ca. 2543-2300 вс) had the primary aim of securing access to mines and procuring exotic goods, as is apparent from Egyptian written records.

The first king of the Fourth Dynasty, Sneferu, dispatched an expedition into Nubia that brought back prisoners and booty: the Palermo Stone (a fragment of a Fifth Dynasty king list that included a particular event of each king’s reign) records the capture of seven thousand prisoners, together with two hundred thousand head of cattle. Securing the Second Cataract by building a fort and settlement there against Nubian incursion became a priority of later Fourth Dynasty rulers. Inscriptions indicating these kings’ presence were also found north of the Third Cataract at Kulb.

Khafre of the Fourth Dynasty was evidently interested in Nubian quarrying operations, as the gneiss quarries northwest of Abu Simbel near Toshka yielded stone for his magnificent statue, now in the Cairo Museum. This quarry continued to be exploited during the Fifth Dynasty, as were possibly the gold mines at Wadi al-Allaqi.

There also appear to have been minerals originating at Kulb and Tomas in central Lower Nubia, as indicated by inscriptions there. Other expeditions, such as the one to Punt sent by Sahure and Djed- kare of the Fifth Dynasty, sought to acquire additional exotic goods. Punt is thought to be located adjacent to the Red Sea, though some scholars have suggested locations as far afield as Somalia and Yemen.

By the Sixth Dynasty (ca. 2300-2150 BC), Egyptian military control over Lower Nubia was beginning to fail; instead, trade and alliances with the Nubians became increasingly important in order to secure goods. Mercenaries from throughout Nubia (Wawat, Irtjet, Setju, Yam, Medja, and Kaau) now began to serve in Egyptian armies. The second ruler of the Sixth Dynasty, Pepy I, used these warriors to help fight the Asiatics who were threatening security in the northeast of Egypt.

Egyptian tomb biographies from this era report numerous expeditions to Nubia on behalf of the rulers. Pepy I’s trusted official (and later governor), Weni, inscribed his exploits with the permission of the king on the facade of his tomb chapel: he had ventured to Nubia to procure for Pepy I’s successor Merenre the stone for a sarcophagus, its lid, and a pyramidion.

Weni’s tomb biography makes it clear that Egypt enjoyed peaceful relations with some areas of Nubia, as he oversaw the construction of barges from acacia wood imported from Wawat. Furthermore, he states that foreign chiefs of Wawat, Irtjet, Yam, and Medja (homelands of the Egyptian mercenaries) cut the wood for these ships, indicating either that the Egyptians controlled these areas or, more likely, that they had diplomatic relations with these people and the wood was offered as a tribute or obligation.

An Egyptian tomb biography of the governor Harkhuf at Aswan tells of four expeditions he made to Nubia under Kings Merenre and Pepy II. During Merenre’s reign, he set out to “open the way,” as the biography puts it, to the Nubian district of Yam. From there, he brought back many beautiful and exotic gifts for the king. He then undertook a second expedition, this time through Irtjet to Yam, claiming that this was the first time an Egyptian representative had visited there.

Again he brought back gifts for the king, implying that peace prevailed with this area of Nubia. On a third expedition, Harkhuf returned to Yam, where he reports that the Nubians were fighting among themselves. Harkhuf then followed the chief of Yam to Tjemeh in the west; again they had a peaceful interchange, implying some form of alliance. The conventional view among scholars is that Yam may be associated with Kerma and, if so, that Egypt had begun shifting its interest farther south throughout this period. (O’Connor, however, places Yam in the Butana region.)

Harkhuf’s final expedition also occurred during the reign of Pepy II. He states that three Nubian areas—Wawat, Irtjet, and Setju—were united under one chief. This chief, accompanied by the troops of Yam, greeted Harkhuf with cattle and goats. Harkhuf also brought back to court a pygmy to perform the “dances of the god.” These biographies underscore the complexity of these interactions, the peaceful trade relations that Egypt had with Nubia, and the activities of, and power struggles among, Nubian groups.

Figure. Relief of King Amenemhat I from Lisht North, Pyramid Temple of Amenemhat I, ca. 1939-1875 вс. Photograph courtesy of The Egyptian Department, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Besides using Nubian mercenaries, King Merenre seems to have established a new program to convert Nubian allies to Egyptian customs. Nubian princes were brought back to Memphis, the capital of Egypt at that time, and educated there in the hope that once they returned to their homes in Nubia, they would maintain their Egyptian affiliation. This policy continued under Pepy II.

Despite these frequent excursions and trade relations, Nubia remained an exotic place to the Egyptians, who had no desire to live—or die—in this alien environment. One Sixth Dynasty noble, Sabni, reports in his tomb biography that he led an expedition into the Nubian desert to recover the body of his father, who had died in battle there. Presumably, Sabni wished not to abandon his father in a foreign land but to give him a proper burial in Egypt, to ensure that he reached the afterworld.

With the collapse of centralized control at the end of the Sixth Dynasty, Nubia was once again free to expand northward. Whatever the cause— famine due to low floods, climatic change in the surrounding deserts, the disappearance of certain animals (elephants, giraffes, and rhinoceros), or the breakdown of the centralized government in Egypt—trade between Egypt and Nubia was clearly affected.

Morkot has suggested two possible reasons why the Egyptians deserted previously settled areas in Nubia near the end of the Old Kingdom: 1) the increased migration of non-Egyptian people settling in the Nubian Nile Valley, as well as the rise of Kerma as an urban center, and 2) pressures on Egyptian authority and resources elsewhere. Whatever the reason, maintaining traffic control of these trade bases in Nubia might have proved too taxing for the available resources.

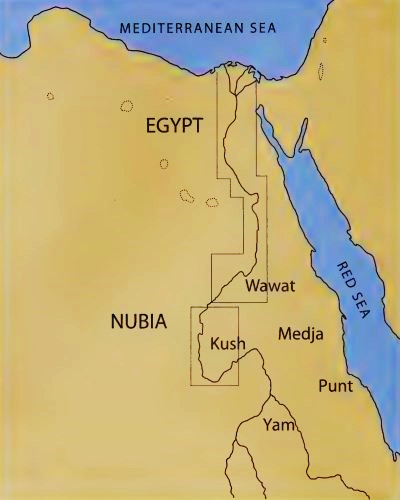

Figure. Map of Egypt and Nubia, ca. 2000-1650 вс. The outlines show the approximate extent of Egyptian and Nubian influence during this period

At the beginning of the First Intermediate Period in Egypt (Seventh to first half of Eleventh Dynasties, ca. 2150-2008 BC), indigenous Nubian populations once again regained control over their land. We do have archaeological evidence from Upper Nubia at this time, most notably from the site of Kerma; as to textual references, in Egypt one inscription from a tomb at Mo’alla mentions grain sent to Wawat in order to prevent a famine, hinting at problems they were experiencing.

Egyptians did not control any part of Nubia, and Nubians seem to have remained at peace with their northern neighbor, most likely to maintain trade relations. By the end of this period, however, Egyptian texts refer to armies being sent into Nubia—but do not reveal the outcome of any hostilities.

During the Egyptian First Intermediate Period and early Middle Kingdom (second half of Eleventh to Twelfth Dynasties, ca. 2009-1760 вс), society in Upper Nubia was clearly changing. Many Nubians still lived and worked in Egypt, and a series of stelae from Gebelein seem to indicate that Nubians and Egyptians intermarried.

One possible product of such a union is an Egyptian relief that portrays the Eleventh Dynasty Egyptian queen Kemsit, whose face is painted black in some depictions and dark pink in others, possibly indicating a Nubian origin. It has been suggested by many scholars that the other wives or consorts of King Mentuhotep II (ca. 2008-1957 BC) may also have been fully or partially Nubian and that even Mentuhotep II himself may have been of Nubian descen.

Whatever his Nubian connection, Mentuhotep II had a comprehensive plan to regain control of Nubia. Aware of the military skill of Nubian warriors, he incorporated Nubians from some regions into his armies to fight Nubians from other regions, thus protecting Egypt’s interests in Nubia and the rest of Africa. This practice of employing Nubian soldiers in Egypt is illustrated by wooden models, found in a tomb in Asyut belonging to a regional leader, depicting a troop of Nubian archers along with Egyptian soldiers.

To ensure that the Nubians kept their distance from Egypt, Mentuhotep II may have built some fortifications in Lower Nubia. Not content with military force, he also used ritual means in his attempt to destroy his Nubian enemies. Execration Texts, characteristic of the First Intermediate Period and Middle Kingdom, list places and people who were perceived by the Egyptians as hostile, and they mention the names of many of these Nubian enemies. When such texts, written upon pots and statuettes of prisoners, were rituälly broken, the intention was that the enemy would magically be destroyed.

Although Nubians were thus mentioned and portrayed on a variety of Egyptian cultural artifacts, little else is known about Egyptian policy in Nubia during this period. There is evidence of three Nubian kings on rock drawings and rockcut inscriptions in Lower Nubia, although some scholars date this to the Second Intermediate Period, but very little can be discerned about these individuals or the nature of their kingdoms.

Date added: 2023-10-02; views: 617;